The secret history of the Nike Air Max, the sneaker inspired by the Centre Pompidou's architecture

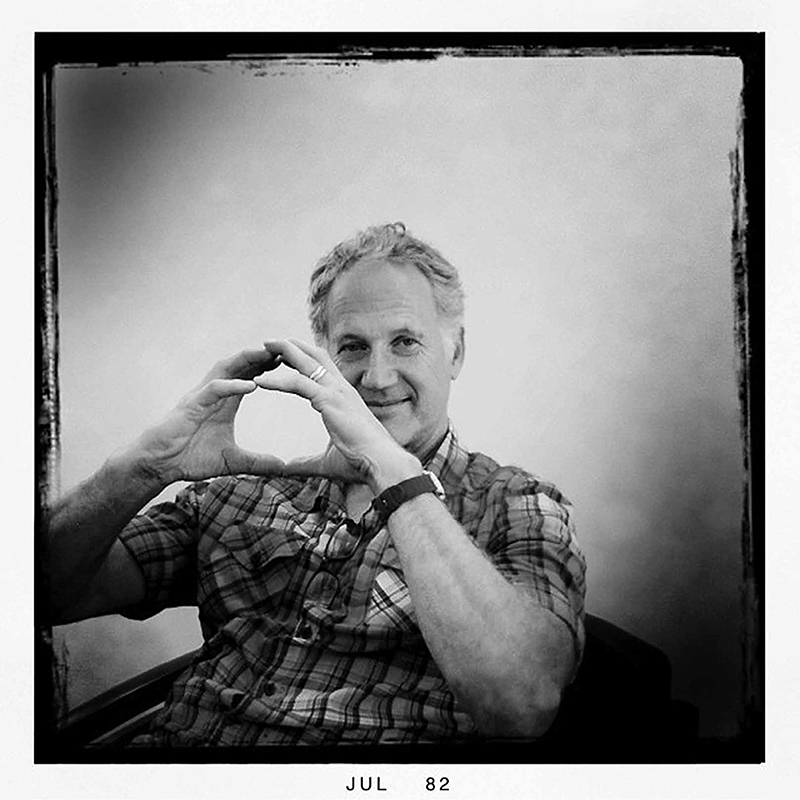

Beaverton, Oregon, 1986. A young thirty-something recently appointed to Nike's Design Department makes an unbelievable proposal during a meeting. His idea was to make the technicality of the Air system—an innovation patented in 1979 using pressurized air in the sole for unparalleled cushioning—visible through a transparent bubble. His name? Tinker Hatfield.

Sold in millions of pairs worldwide and available in dozens of limited editions, the Air Max is now a true totem of sneaker culture.

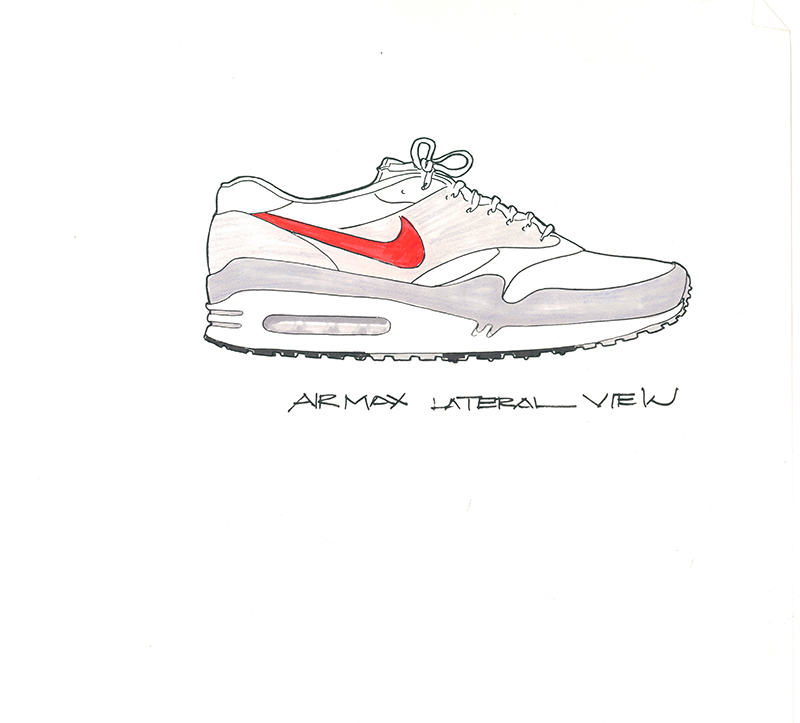

Initially, his idea is met with strong resistance from the company's executives, who fear customers will be put off by the apparent fragility of such a sole. However, in 1987, the brand launches a new running shoe featuring the famous visible air bubble: the Air Max 1. Entirely designed by Tinker Hatfield, it rapidly becomes a hit. Sold in millions of pairs worldwide and available in dozens of limited editions, the Air Max is now a true totem of sneaker culture. In 2017, to celebrate the 30th anniversary of Hatfield's iconic model, Nike even released an Air Max in colors directly inspired by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers' building. Between Nike and the Centre Pompidou, it is somewhat of a love story...

Paris, mid-1980s. Tinker Hatfield is in town. And he has one wish: to see the Centre Pompidou. Hatfield, a former university pole vault champion, is also a trained architect. Since joining Nike in 1981, the man has been responsible for designing showrooms and stores. In 1985, his mentor Bill Bowerman (one of the brand's founders), noticing his drawing skills, advised him to join the design team. In Abstract: The Art of Design, a Netflix series dedicated to artists and designers, Hatfield recalls, "I discovered almost by accident that I was good at drawing, it was a real surprise to me!"

The Centre Pompidou was a must-see for me, I had to go!

Tinker Hatfield

Inaugurated a few years earlier, in February 1977, the metal and glass giant was still a bone of contention to many Parisians—some even affectionately nicknamed it "Notre-Dame-des-Tuyaux" (Our Lady of Pipes). But Hatfield, an iconoclast, is curious to see firsthand the building conceived by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers. In Respect The Architects, a short film made by Thibaud de Longeville for Nike in 2006, Hatfield recounts, "The Centre Pompidou was a must-see for me, I had to go! Coming into the Piazza, I was struck by the stark contrast between the traditionnal style of the Parisian buildings—mansard roofs, small windows—and this almost machine-like building sort of spilling its guts out into the world... Everything was visible, air conditioning, escalators, heating, the different levels..."

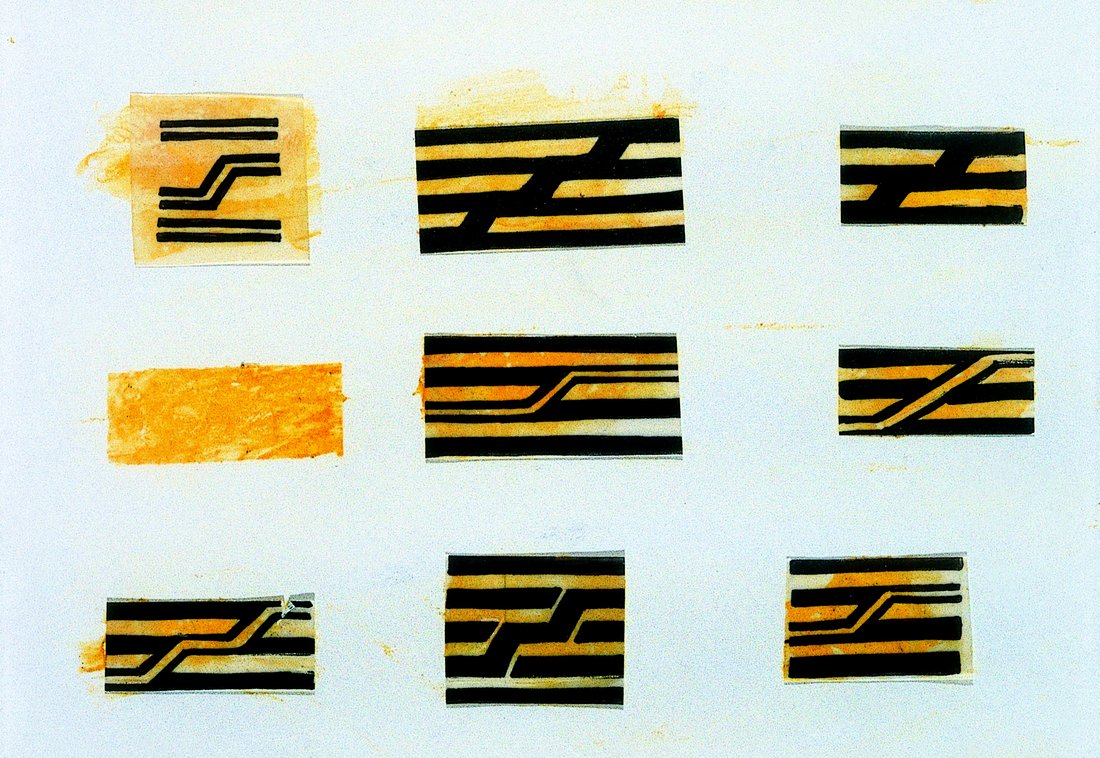

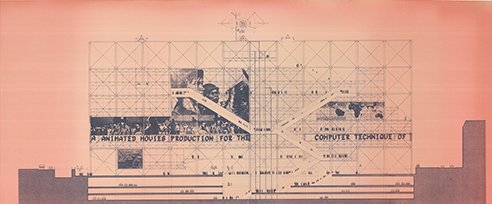

This was Piano and Rogers' groundbreaking idea: to externalize all the building's infrastructure, leaving six levels of 7,000 square meters of fully modular open space. Renzo Piano summarized the project as such: "On the Piazza and outside the usable volume, we gathered all the public transportation facilities. On the opposite side, we externalized all the technical equipment and pipelines. Thus, each floor is completely free and usable for any form of cultural activity known or yet to be invented." The structure was conceived as a giant construction set, with repeating, assembling, and interlocking elements forming an open, metallic framework. The escalator on the facade, famously known as the "Chenille" ("caterpillar") acts as a visual signature, eventually becoming the logo for Beaubourg, thanks to the genius of designer Jean Widmer.

This radical vision left a profound mark on the young Hatfield. More than that, it provided him with a true aesthetic epiphany: "It really inspired me because it shook the world of architecture and urban design. It really changed our way of understanding the city. For many things had changed for the worst—but in my eye, they had changed for the better."

[Translate to English:]

[Translate to English:]

Inauguré quelques années auparavant, en février 1977, le colosse de métal et de verre divise toujours autant les Parisiens – certains l'ayant même affublé du tendre sobriquet de « Notre-Dame-des-Tuyaux ». Mais Hatfield est un iconoclaste, et il est curieux de voir de ses propres yeux le bâtiment sorti du cerveau de Renzo Piano et Richard Rogers. Dans Respect The Architects, un court métrage de 2006 réalisé par Thibaud de Longeville pour Nike, Hatfield raconte : « Le Centre Pompidou était vraiment un incontournable pour moi, je devais absolument y aller ! Dès mon arrivée sur la Piazza, j’ai été frappé par le fort contraste entre les immeubles à l’architecture typique de Paris – toits mansardés, petites fenêtres – et le bâtiment, semblable à une sorte de machine dont on verrait les entrailles… Tout était visible, escalators, systèmes de climatisation et de chauffage, étages intérieurs et même visiteurs ! »

Le Centre Pompidou était vraiment un incontournable pour moi, je devais absolument y aller ! Dès mon arrivée sur la Piazza, j’ai été frappé par le fort contraste entre les immeubles à l’architecture typique de Paris – toits mansardés, petites fenêtres – et le bâtiment, semblable à une sorte de machine dont on verrait les entrailles…

Tinker Hatfield

Car c’est là l'idée novatrice de Piano et Rogers : rejeter sur l'extérieur du bâtiment toutes les infrastructures liées au fonctionnement interne pour laisser libres sur six niveaux des plateaux de 7 000 m2,entièrement modulables. Renzo Piano résume ainsi le projet : « Sur la Piazza et à l’extérieur du volume utilisable, on a rassemblé tous les équipements du mouvement du public. Sur le côté opposé, on a centrifugé tous les équipements techniques et les canalisations. Ainsi chaque étage est-il complètement libre et utilisable, pour toute forme d’activité culturelle connue ou à trouver. » L’ossature de l’ensemble est quant à elle conçue comme un jeu de construction géant, les éléments se répètent, s’assemblent et s’imbriquent, formant un engrenage régulier métallique complètement ouvert. Et sur la façade, l’escalator qui zèbre le bâtiment (la fameuse « Chenille ») fonctionne comme une véritable signature visuelle (jusqu'à devenir le logo de Beaubourg grâce au génie de Jean Widmer).

Une vision radicale pour l'époque qui marque le jeune Hatfield. Mieux, il vit une véritable épiphanie esthétique : « Le bâtiment de Piano et Rogers a vraiment secoué le monde de l’architecture et du design urbain. Il a changé notre manière d’appréhender la ville. Certains pensent que c’est pour le pire – moi je pense le contraire. »

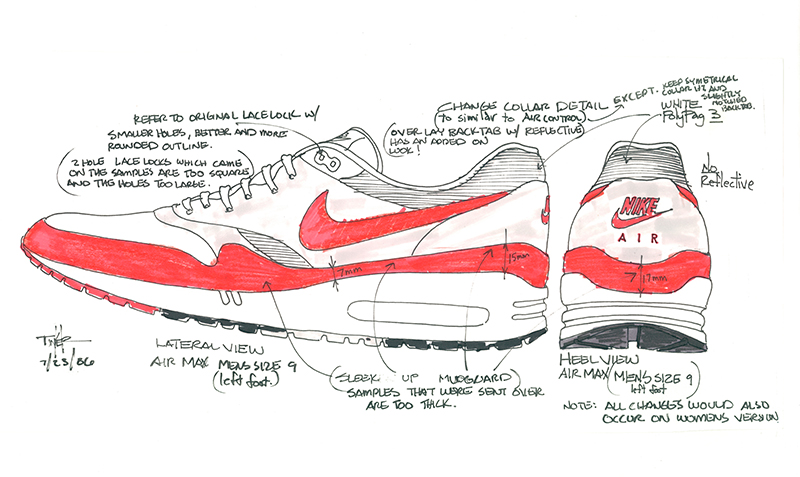

For his Air Max, the designer adopted Piano and Rogers' idea: making the usually hidden visible. He also drew inspiration from the transgressive colors chosen by the architects for their building: blue for air circulation, yellow for electrical, green for water, and red for people movement. At the time, Nike's running shoes, especially the "Waffle" (worn by champion Steve Prefontaine in 1974), were already designed in flashy primary colors. But for the Air Max 1, Hatfield took it even further: he designed it in red and white. "Piano and his team wanted the building to be visible from a distance, to be strinking—and maybe shock people a little more. And that's what happened with the Air Max: I wanted to push things as far as possible without being fired!" the designer recounts humorously.

Piano and his team wanted the building to be visible from a distance, to be strinking —and maybe shock people a little more. And that's what happened with the Air Max: I wanted to push things as far as possible without being fired!

Tinker Hatfield

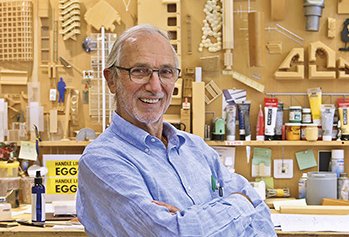

Far from being fired, Tinker Hatfield became one of Nike's design stars. He isthe man behind several models of the Air Jordan, a bestseller originally designed for basketball player Michael Jordan. He also designed the famous self-lacing Nike Air Mag from Back to the Future Part II, which became a reality in 2015, and the shoes for Tim Burton's Batman. Today, at 72, Hatfield is the Vice President of Design & Special Projects at Nike. Looking back at his career, he tends to borrow his idol Renzo Piano's words: "People resist things they don't understand, and designs different from what they are used to. But what creates excitement is seeking out what disturbs, what we later call 'a big idea.' That's what I do, that's my job." Hatfield's ultimate dream? To meet Renzo Piano, now 86 (Richard Rogers passed away in 2021). But what does the Italian architect think of this improbable tribute? With his usual elegance, il maestro admits "not knowing much about sports shoes," but says he is "very flattered" to have inspired Hatfield so much... The story doesn't say whether he wears Air Max. ◼

Related articles

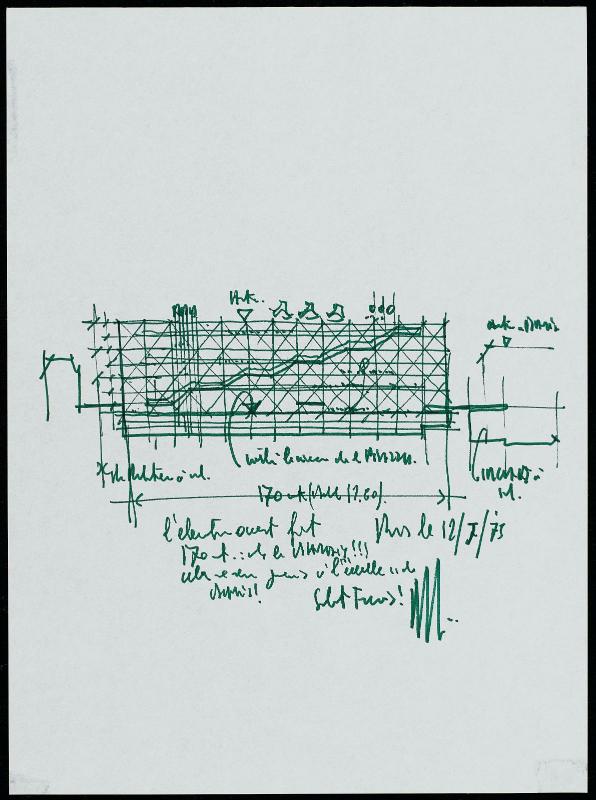

A sketch for the Nike Air Max 1 by Tinker Hatfield

© Nike

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/user_upload/DaftPunk-vignette.jpg)