Architectural Secrets ► The ‘Piazza’ of the Centre Pompidou

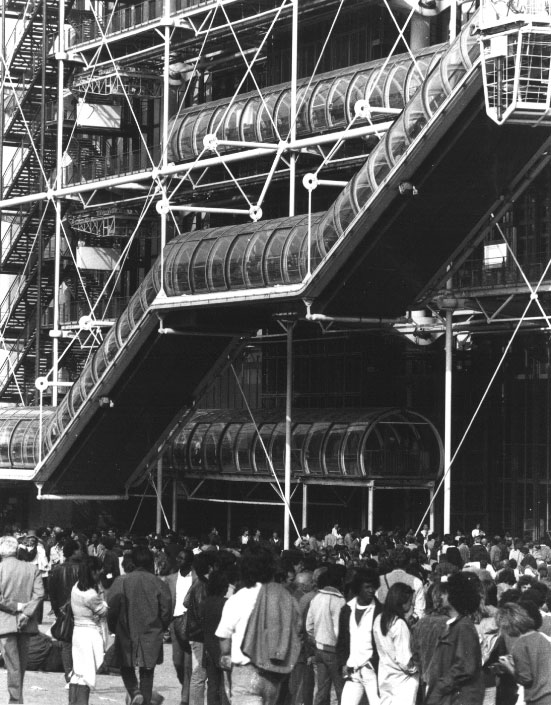

The Piazza, an integral part of the Centre Pompidou, is that famous, gently sloping square that gathers onlookers and passers-by along the south-west façade of the celebrated, pipe-clad building. More than that, it is said to be among the reasons why, in 1971, the jury chose “project 493” from the 681 proposals submitted for the future Centre Pompidou.

In February 1977, in the magazine L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui, the president of the jury, French architect, designer, and engineer Jean Prouvé, revealed that “most of the other schemes filled, like big paving stones, the entire site, rising to heights of 30 to 50 metres, and even 150 metres for a few”.

Most of the other schemes filled, like big paving stones, the entire site.

Jean Prouvé

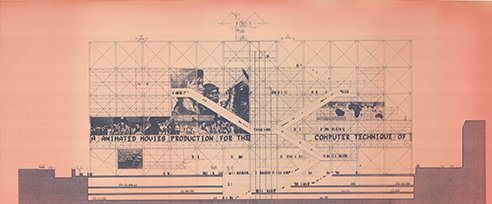

Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers’ winning proposal was one of the few to incorporate such a generous measure of empty space, with a large public agora. This almost Taoist balance remains one of the project’s great strengths. Their big urban idea is the double play of views enabled by the Piazza, which offers a perfect horizontal counterpoint to the Centre’s façade. From the external escalator, the square becomes a picture animated by tiny figures. Conversely, for passers-by, the building acts like a giant television—even if it was not, as its designers first intended, covered with continuous information screens—in which the visitors of the Centre and the Public Information Library (Bpi) bustle about.

Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers’ winning proposal was one of the few to incorporate such a generous measure of empty space, with a large public agora.

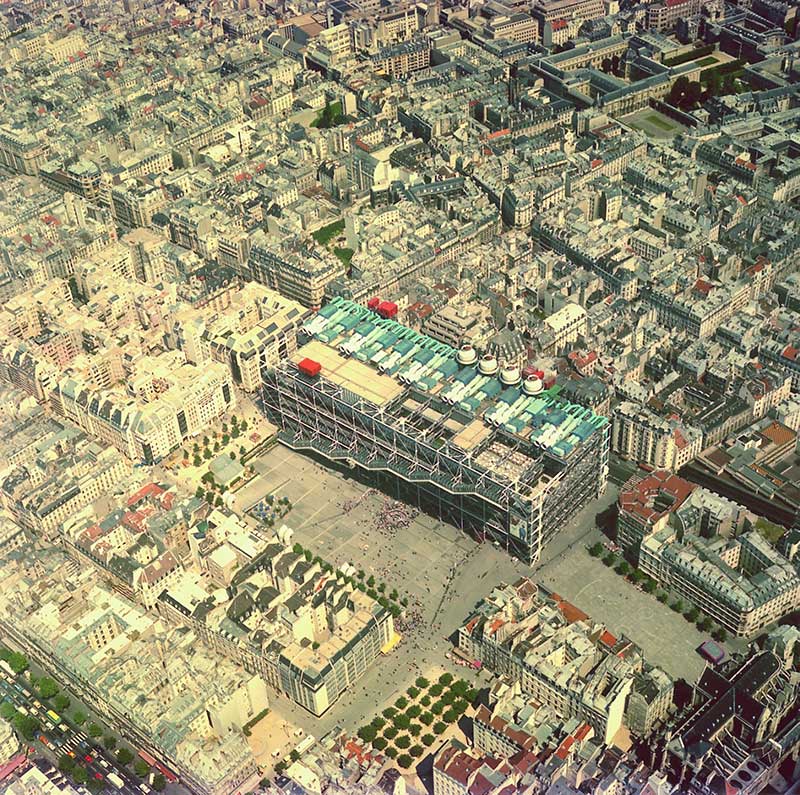

The Piazza is simple in conception: a rectangle measuring 170 by 65 metres. Like the whole of the Centre Pompidou, it was built on the site of a gigantic car park, itself constructed over a blighted block cleared in the 1930s. Paved in granite, pedestrian-only, and heavily frequented, it could easily be mistaken for any other Parisian square.

So what makes the Piazza so distinctive? Its defining feature is its 11% slope; only a few metres in elevation separate its highest point on Rue Saint Martin from the entrance to the Forum. One descends it gently, like a slipway into water. This characteristic has earned it frequent comparison to its likely inspiration, Siena’s Piazza del Campo in Italy, which has been leaning since the 13th century like an amphitheatre (or a scallop shell) towards the city’s town hall.

Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers have said their ambition was to give the neighbourhood “a place for all people”.

Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers have said their ambition was to give the neighbourhood “a place for all people”. Creating a car-free square in Paris was rare at the time. From day one, the Piazza averaged 25,000 visitors a day—well above projections. It acts as a natural spillway for crowds arriving from the district’s major arteries: Les Halles, and Rues Rambuteau, Saint Merri, and Saint Martin. By creating a powerful draw next to Les Halles—the “Belly of Paris”, to quote Émile Zola—the Centre Pompidou established a new centre that has never waned in popularity since.

Its gradient sits poorly with order: the Piazza’s joyful chaos escapes the Centre Pompidou’s control. The slope becomes tiered seating for the audiences of the many buskers, artists, and fire eaters who forged its legend. On the Piazza one can “live on the oblique”, to borrow architect Claude Parent’s exhortation. Some of the performers who appeared there have entered local lore, such as Gilbert the automaton, the philosopher tramp Aguigui Mouna, or John Guez, who staged major works from theatre history by assigning roles to passers-by.

The boundary between inside and outside was so thin that everyone found themselves in the Forum—even people who would never have set foot in a museum.

Julien Donada

The square’s current form—ultimately rather restrained in its design—is the product of compromises and renunciations. After their scheme was selected, its designers, steeped in libertarian ideals, began to dream of a hallucinatory, hyper-connected Piazza. They even imagined covering it with an “active surface” in the form of a “technological lawn”, an interactive skin that would have spilled out across the entire neighbourhood, irrigating it with information flows from the Centre.

It is worth noting how easy it is to reach the Forum from the Piazza. Visitors encounter virtually no threshold effect. It is not an intimidating entrance: there is no monumental staircase and no heavy door. As filmmaker Julien Donada, director of the documentary La Folle Histoire du Centre Pompidou (2016), confides, “c”. In the initial scheme, the doors were to remain open, like a station concourse. The Parisian climate decided otherwise.

After their scheme was selected, its designers, steeped in libertarian ideals, began to dream of a hallucinatory, hyper-connected Piazza.

Playing on this porosity, the institution has often occupied the public space by placing monumental works on the Piazza, exporting the museum directly into the city. Set out on the forecourt, these sculptures have sparked passionate, never-ending debate—such as Jean Pierre Raynaud’s Pot doré (1985) or Adel Abdessemed’s Coup de Tête (2012), depicting the blow delivered to the solar plexus by footballer Zinédine Zidane to Marco Materazzi during the 2006 World Cup final.

In 2030, the Centre Pompidou’s reopening after renovation will extend the Piazza’s story. The project, to be carried out by the agency Moreau Kusunoki (in association with Frida Escobedo Studio), will add steps and an accessibility ramp to the Piazza, so that everyone can be part of the scene. If Paris is a party, the Piazza will remain its dance floor. ◼

Related articles

The Piazza, Centre Pompidou (2016)

Photo © Manuel Braun

Discover Hugo Trutt’s urban architecture tours at https://croquebrique.com.