![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/9/0/csm_Iolas-Warhol-bandeau_2229828cb7.jpg)

Behind the Scenes of Alexander Iolas: Discoverer of Warhol, Patron of the Pompidou

New York, 1949. A young man in his twenties walks past the Hugo Gallery on 55th Street, just steps from MoMA. Tucked under his arm: a portfolio. The gallery owner, one Alexander Iolas, stops him and asks what’s inside. “My lunch,” replies Andrew Warhola, with a touch of humour. At the time, the man who had yet to become the pope of Pop Art was earning his living as a commercial illustrator, producing drawings for fashion houses, department stores (including Bergdorf Goodman), and magazines such as Glamour. He had only just arrived in Manhattan from his native Pittsburgh. “This is the last day of your life you’ll spend drawing shoes,” Iolas is said to have told him.

From that moment on, the paths of Warhol and Iolas would become inextricably linked — the former going on to become the most famous American artist of his time, the latter one of the most influential gallerists of the 20th century.

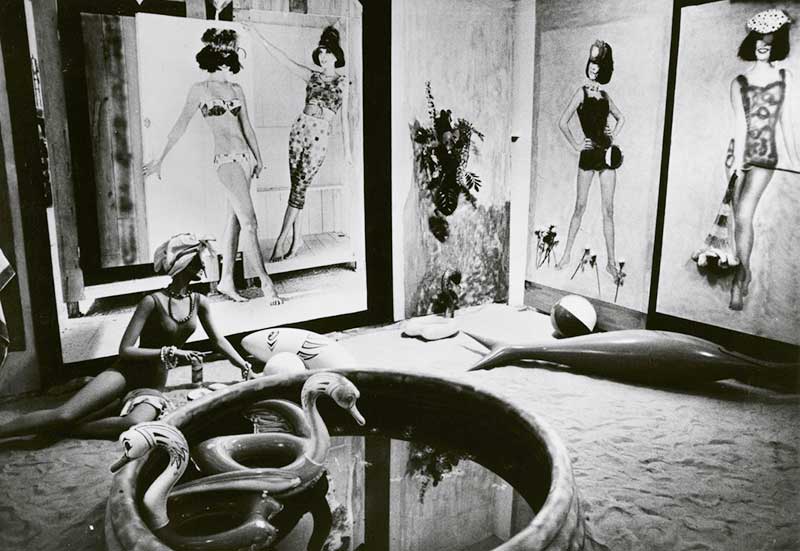

In the summer of 1952, Iolas and the Hugo Gallery staged Andy Warhol’s very first exhibition: “Fifteen Drawings Based on the Writings of Truman Capote”. The series drew inspiration from the book In Cold Blood author, Warhol was an obsessive and unapologetic admirer of Capote.

From that moment on, the paths of Warhol and Iolas would become inextricably linked — the former going on to become the most famous American artist of his time, the latter one of the most influential gallerists of the 20th century.

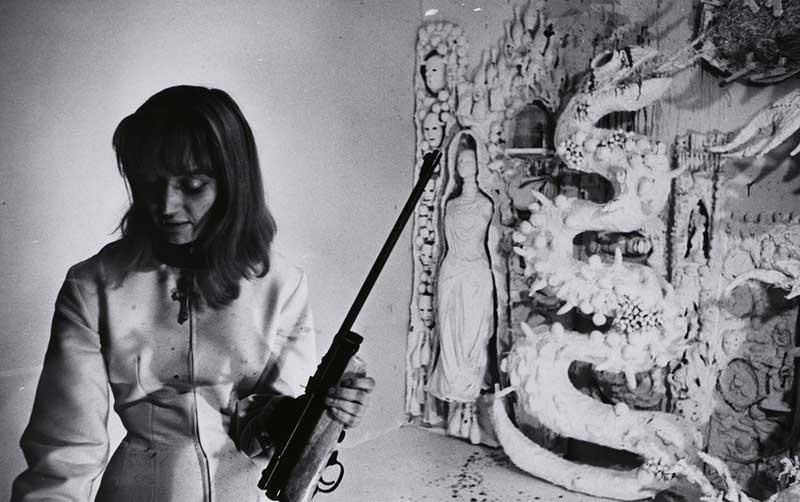

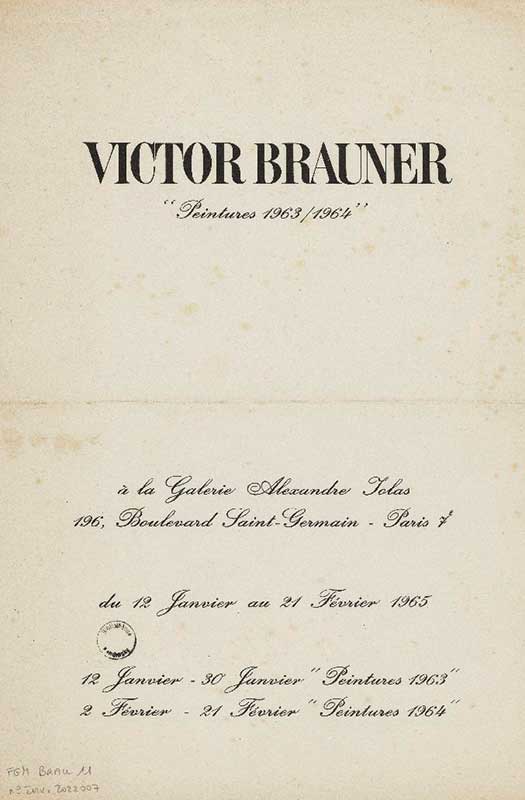

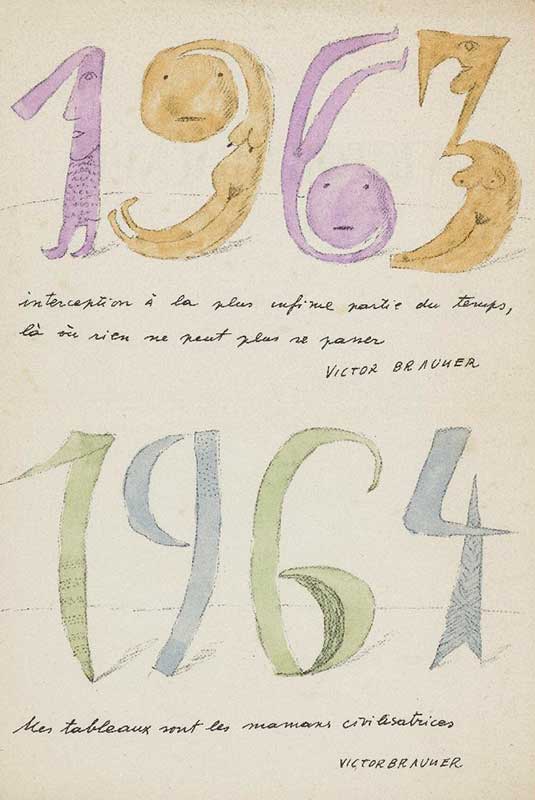

Little known to the wider public, Alexander Iolas nonetheless played a pivotal role in the careers of numerous 20th-century artists — most notably the Surrealists, including Max Ernst, Victor Brauner, René Magritte, Dorothea Tanning, Leonor Fini and Roberto Matta. He would also champion members of the Nouveau Réalisme movement such as Jean Tinguely, Niki de Saint Phalle, Martial Raysse and Yves Klein.

Gifted with an exceptional eye and an enviably thick address book, Iolas advised many of the great art patrons of his day — among them the British collector Pauline Karpidas and the Franco-American couple Dominique and John de Menil, founders of the Menil Collection in Houston, Texas.

He was quite a character! Brilliant, intuitive, perverse, funny — and truly passionate about his work. He could shut himself away for two days before a private view, alone with the works.

Niki de Saint Phalle

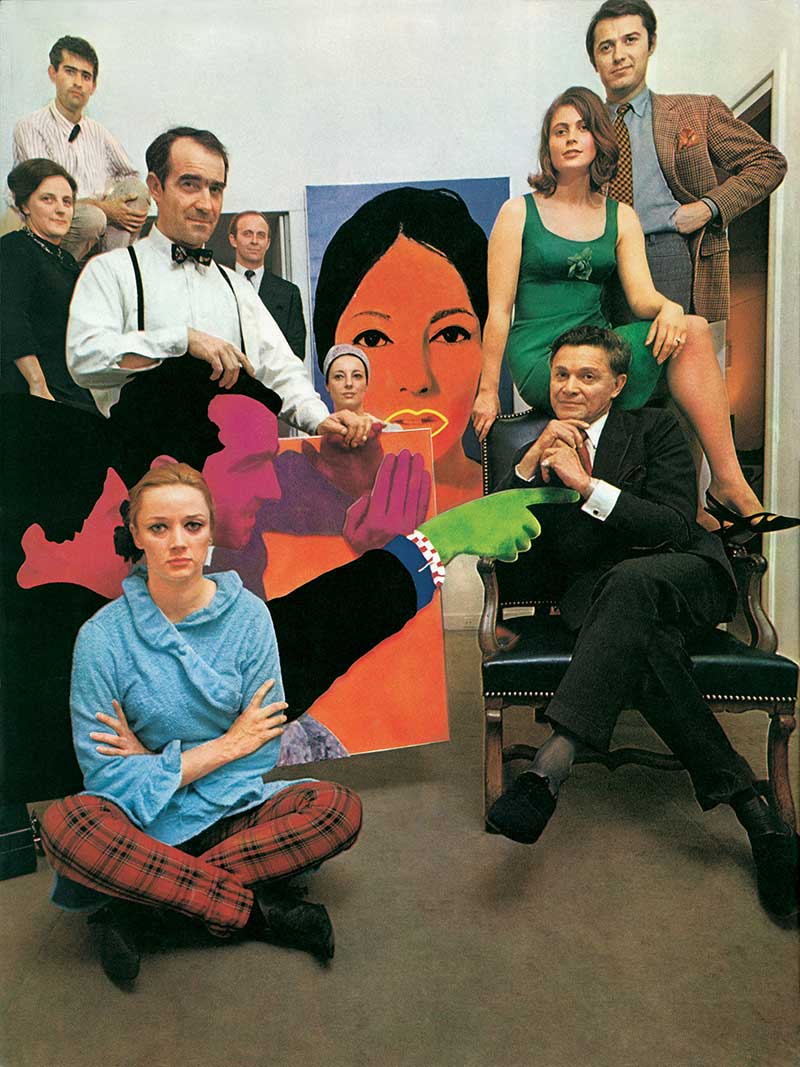

His galleries — in New York, Paris, and later Madrid, Rome, Geneva and Athens — hosted some of the most significant exhibitions of the 1960s and ’70s. Iolas played a key role in launching the careers of several major figures in contemporary art — including Niki de Saint Phalle, who regarded him as a true friend.

“He was quite a character! Brilliant, intuitive, perverse, funny — and truly passionate about his work,” the artist recalled (as quoted in the exhibition catalogue Un peu de mon histoire avec toi, Jean). “He could shut himself away for two days before a private view, alone with the works. He would even sleep in the gallery and refused to leave until the hanging was exactly as he wanted it.”

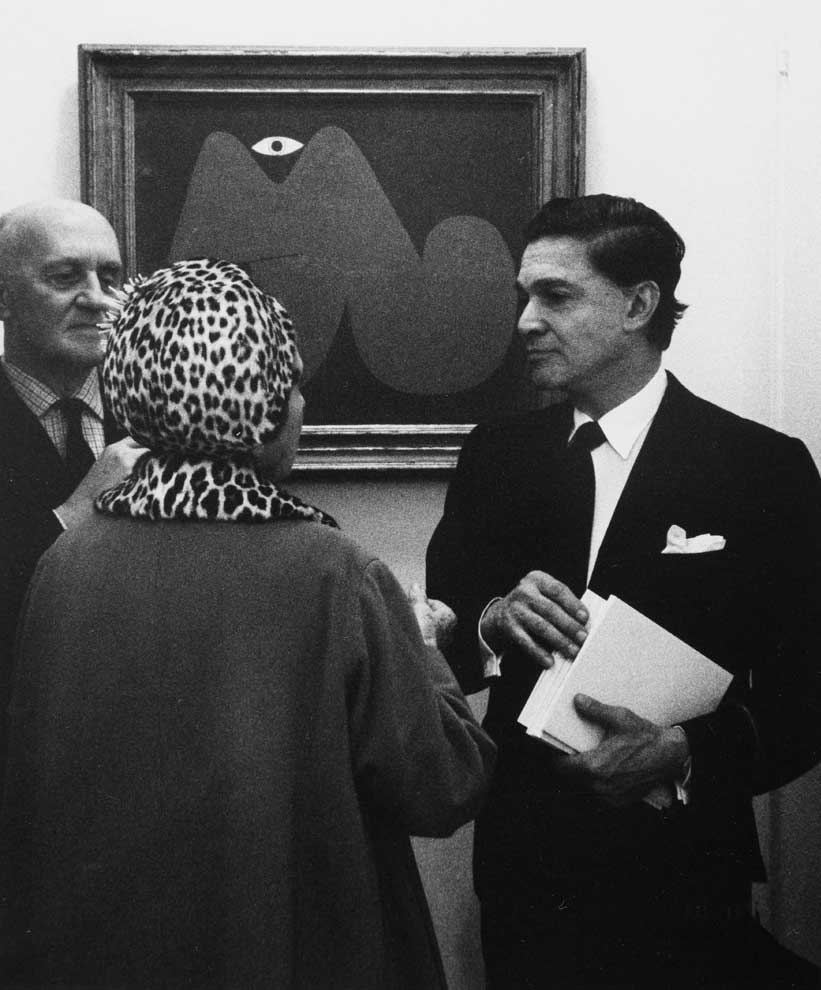

Openly homosexual and flamboyantly social, Iolas both impressed and beguiled those around him. In Niki de Saint Phalle, la révolte à l’œuvre, a key biography of the artist, art historian Catherine Francblin describes him as “dark-haired, supremely elegant […] a larger-than-life figure, and a great seducer.”

I never sell a painting. I make people fall in love with the painting I love.

Alexander Iolas

Unlike other gallerists — some driven by more crudely material ambitions — Iolas cultivated the image of an artist among artists, many of whom regarded him as one of their own. He even refused to describe himself as an art dealer. In an interview with Vogue in August 1965, he declared: “I never sell a painting. I make people fall in love with the painting I love.”

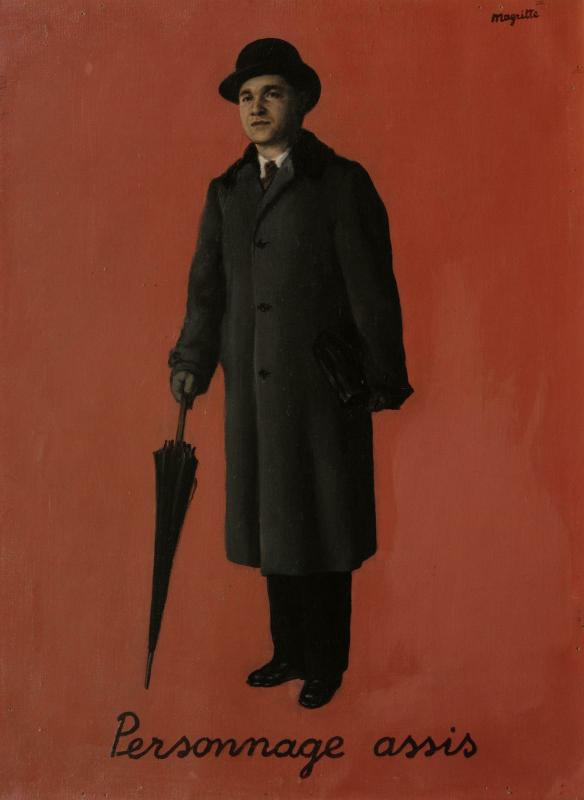

In the 1970s and ’80s, Alexander Iolas donated several major works to the Musée National d’Art Moderne — amongst them Tableau métallique: portrait à géométrie convexe (1964) by Martial Raysse, and a portrait of himself by René Magritte, titled Le bon exemple (1953).

“Iolas is the dealer who not only helped secure Magritte’s reputation in America, but also contributed to his financial success,” explains Didier Ottinger, Deputy Director of the Musée National d’Art Moderne and curator of the recent exhibition “Surrealism”.

.

It wasn’t all smooth sailing, however: “The correspondence between Magritte and Iolas on the subject is rather entertaining… At the time, Magritte had entered what is known as his ‘Renoir period’, revisiting Impressionist techniques. Iolas told him he needed to paint like he used to — because that’s what the market wanted. That caused a bit of soul-searching for Magritte, who had been close to the Communist Party before the war,” Ottinger adds.

Iolas is the dealer who not only helped secure Magritte’s reputation in America, but also contributed to his financial success.

Didier Ottinger, Musée National d’Art Moderne

And yet the artist complied, producing what he himself called “replicas” of his works from the 1930s. This did not sit well with the more radical wing of the Belgian Surrealist circle — including Marcel Mariën, who in 1962 printed fake banknotes bearing Magritte’s face in place of the Belgian king’s.

But the dealer had judged the moment perfectly. Magritte became a darling of American collectors. And Iolas, the king of gallerists.

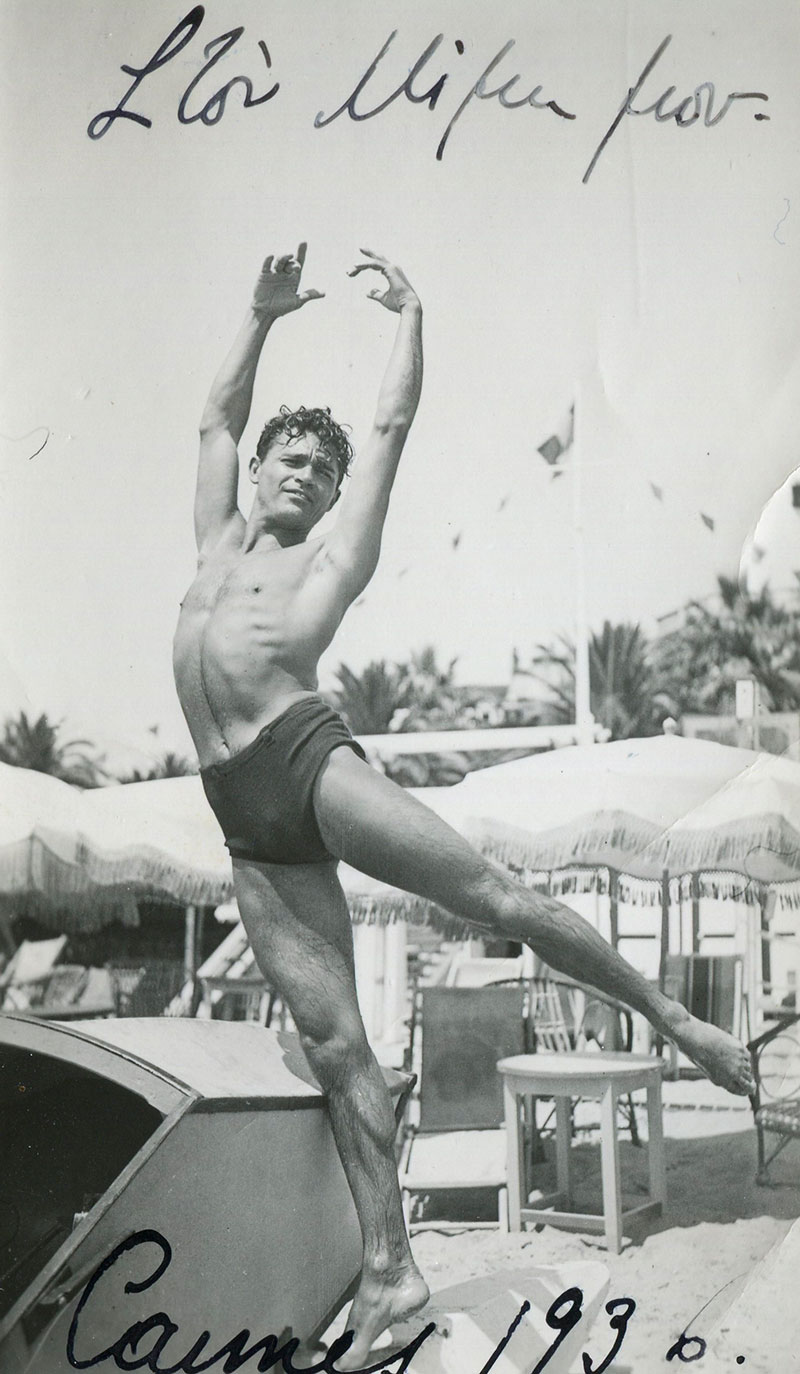

Alexander Iolas lived a thousand lives. Born Konstantinos Koutsoudis in Alexandria in 1908, he adopted the pseudonym “Iolas” early on — a reference, in ancient Greek, to a companion of the mythological hero Heracles. The son of a Greek middle-class merchant family based in Egypt, he set his sights on an artistic career from adolescence. He chose dance, studying first in Athens at the age of seventeen, and later in Berlin.

In 1932, he arrived in Paris and enrolled at the Sorbonne to study art history. There, he formed several key relationships — notably with Florence Meyer, a socialite and photographer close to Man Ray and Constantin Brancusi. It was thanks to Meyer's father, the influential owner of the Wall Street Journal, that Iolas would later obtain his green card in 1945. He also became close to Theodora Roosevelt, granddaughter of the American president and herself a dancer.

Iolas recounted that his love of modern art began in Paris in 1933, in a gallery on Rue Marignan, when he found himself mesmerised by Melancholy, a painting by Giorgio de Chirico. He bought the work on credit, and later described this moment of epiphany as the spark that would one day inspire him to open a gallery of his own.

Graceful and strikingly handsome, Alexander Iolas danced alongside George Balanchine at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, amongst other venues. He became a leading figure in the celebrated company of Jorge Cuevas Bartholin, known as the Marquis de Cuevas, and toured the world. But in 1944, an injury brought his stage career to an end. Iolas then embarked upon new path — that of the gallerist.

In a now-legendary interview, Iolas recounted that his love of modern art began in Paris in 1933, in a gallery on Rue Marignan, when he found himself mesmerised by Melancholy, a painting by Giorgio de Chirico. He bought the work on credit, and later described this moment of epiphany as the spark that would one day inspire him to open a gallery of his own.

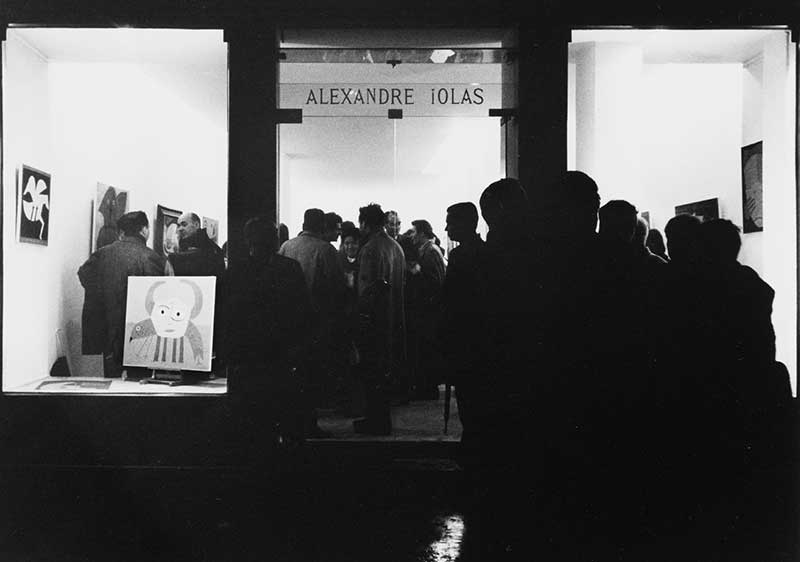

By 1945, Iolas was living in New York, moving within the city’s artistic circles and forging a particularly close friendship with Max Ernst. In 1946, he took over the Hugo Gallery on 26th Street. And in 1953, he finally opened his own gallery in Manhattan — the first to bear his name alone.

Having become a star amongst art dealers, Alexander Iolas never forgot his roots. From the 1950s through to the 1970s, he oversaw the construction of a sprawling modernist villa — some 18,000 square metres — perched on the hills of Agia Paraskevi, just outside Athens.

He settled there in the 1970s, transforming the property — a lavishly rococo-style residence — into a kind of private gallery, where he would present highlights from his prodigious collection to visiting guests of distinction. The “Villa Iolas” soon became a coveted address on the international jet-set circuit, its glittering dinner parties hosted by the master of the house becoming legendary in their own right.

Yet decline was looming. In 1974, with the fall of the military junta (a dictatorship established following the 1967 coup d’état), Alexander Iolas fell into a kind of disgrace — accused by some of having been too close to the former regime. Unfounded allegations of art trafficking and homophobic rumours, fuelled by the Greek tabloid press, further tarnished his image.

In 1974, with the fall of the military junta (a dictatorship established following the 1967 coup d’état), Alexander Iolas fell into a kind of disgrace — accused by some of having been too close to the former regime.

The 1980s proved increasingly difficult for Iolas, who eventually chose to close all his galleries. One final act of brilliance: in 1985, at his suggestion, Andy Warhol created The Last Supper, a work inspired by Leonardo da Vinci’s iconic fresco. It would be Warhol’s final painting — the artist died in February 1987, shortly after the exhibition’s opening at the Palazzo delle Stelline in Milan. Suffering from AIDS, Iolas died just months later, on 8 June 1987, in New York — only a short time after the passing of the Pope of Pop.

After his death, the Villa Iolas was looted and vandalised, and left abandoned for nearly four decades. Acquired by the local municipality in 2015, the villa is now set to be restored and transformed into a cultural venue — a fitting tribute to the extraordinary legacy of a man who never stopped dreaming of being an artist himself. ◼

Related articles

In the calendar

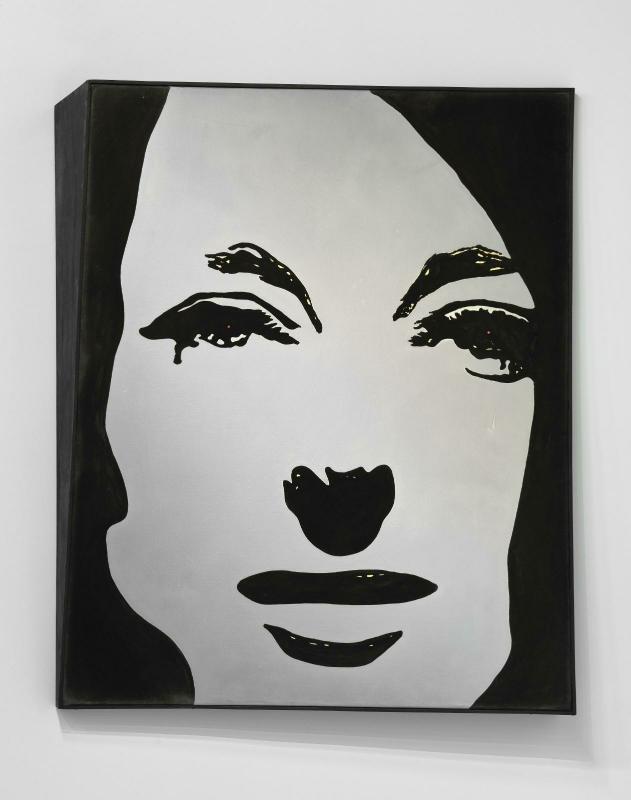

Andy Warhol, Alexander Iolas (1974)

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS Images

Synthetic polymer paint and silkscreen ink on canvas

40 x 40 inches

Takis, Mur magnétique n° 9 (Rouge) 1961 / 1972

Présentation dans l'exposition "Takis" au Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 18 février au 17 mai 2015.

© Adagp, Paris

© Centre Pompidou, Mnam-Cci/Dist. GrandPalaisRmn