“Black Paris”: Towards a Pan-African and Transnational History of Art

The exhibition “Black Paris” maps the presence of one hundred and fifty African, African American, and Caribbean artists in Paris from 1947—the year of the founding of the anticolonial journal Présence Africaine—to the 1990s, marked by the fall of the apartheid regime and the emergence of the magazine Revue Noire. Confronting both historiographical and material challenges—due to the marginalisation of these artists, the dispersion or even disappearance of their works across continents, and the critical and editorial gaps surrounding their practices—the exhibition retraces, for the first time within a French national institution, fifty years of artistic emancipation and expression in Paris.

A true Pan-African laboratory, the French capital played a pivotal role in the redefinition of modernism and postmodernism in the second half of the twentieth century.

A true Pan-African laboratory, the French capital played a pivotal role in the redefinition of modernism and postmodernism in the second half of the twentieth century. “Black Paris” begins with a transnational art history rooted in what Pap Ndiaye terms the “Black condition”, a historical situation inherited from slavery and colonisation, which gave rise to what Paul Gilroy famously called the “Black Atlantic”. From this oppression emerged Afro-Atlantic cultures in both Europe and the Americas, united as “a nation not founded on territorial or linguistic claims, but on shared motifs [...] forged through processes of exclusion and domination around Blackness”, one that, as Amzat Boukari-Yabara notes, “reclaims the racial stigma and transforms it into a weapon of liberation” in the postwar period (see Amzat Boukari Yabara).

The 1950s witnessed the structuring of this struggle through alliances between the Americas and Africa, supported by theoretical frameworks often born in the Caribbean in the wake of the Haitian Revolution. Thinkers such as Cyril Lionel Robert James and Marcus Garvey paved the way for Pan-Africanism at the dawn of the twentieth century. They were followed by Martinican intellectuals, including Suzanne and Aimé Césaire, Frantz Fanon, and Édouard Glissant, who developed a new Black consciousness that wove together philosophy, psychiatry, politics, and poetry. From the 1940s onwards, this consciousness took shape as a cultural movement—Négritude—but also through other forms of Black humanism, as pioneered by the Martinican thinker Paulette Nardal.

This internationalism initially took shape within Europe—particularly in Paris, Rome, and the Scandinavian countries, where several artists found refuge—before extending to the African continent, as evidenced by the history of the Paris and Rome congresses and the Pan-African festivals, from Dakar in 1966 to Festac’77 in Lagos. In the late 1940s, while African Americans fled segregation and South Africans apartheid, many figures committed to emancipation converged in Paris—even as France remained a colonial empire. The central position of the City of Light prompts a reflection on the unique role played by European capitals in shaping what Okwui Enwezor and Chika Okeke-Agulu have termed “the art of decolonisation”, a concept they explored in the exhibition “The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945–1994” (2001).

Such a movement is not solely driven by the pursuit of sovereignty, but also by ideals of fraternity and equality—“the liberation of humanity”, as Aimé Césaire put it to Sarah Maldoror in One Man One Land (1976), the film she dedicated to him. This movement spans the period from the 1950s to the fall of apartheid in South Africa in the late 1980s, with Paris evolving from a centre of a Black “Internationale” to a locus of multicultural France.

At the heart of this emancipatory process, Paris played two pivotal roles: as a space where artists forged alliances and questioned forms of belonging, and as a transit point between the Americas and Africa. Its status as a historic capital and crossroads of the avant-garde enabled artists to connect tradition and modernity and, in so doing, to assert—often for the first time—their freedom to create without externally imposed programmes. During these decades of liberation, artists sketched out iconographies for future nation-states as well as transnational, Pan-African, Pan-American, or radically open representations. The artistic sphere, in which various practices—at times politically engaged, at others deliberately withdrawn or situated within a space of cultural translation—were negotiated, rendered Paris a complex site of experimentation.

At the heart of this emancipatory process, Paris played two pivotal roles: as a space where artists forged alliances and questioned forms of belonging, and as a transit point between the Americas and Africa. Its status as a historic capital and crossroads of the avant-garde enabled artists to connect tradition and modernity.

This intersection of “political emancipation and cultural self-awareness” was foundational: both Aimé Césaire and Léopold Sédar Senghor, a Senegalese politician and poet, considered culture a privileged vehicle of affirmation, while the presence of African American artists and intellectuals in the French capital since the early twentieth century significantly enriched the historiography of the Harlem Renaissance. This legacy is embodied in the ongoing work of artists who also served as cultural mediators, such as Loïs Mailou Jones and Raymond Saunders.

Approaching this history through the lens of art opens the field of identity discourse to other imaginaries. One of the key aims of the exhibition is to understand how these art histories—deeply entangled with political contexts and widely scattered due to processes of circulation and exile—give rise to both singular and relational aesthetics within a longstanding framework of institutional marginalisation. While Paris offered a unique space of solidarity between Africa and the Americas, France has never shed light on its role in the emergence of Black cultural practices: the French political system remains resistant to questions of race, as well as to a redefinition of sovereignty in the postcolonial era.

This blind spot—central to French history—raises numerous questions. Which Afro-Atlantic categories should be asserted: autonomous entities or interconnected branches? What kind of Pan-African art history can be written? How should we revise our understanding of modern and postmodern movements accordingly? Where do we situate memorial practices that use exile and the ghosts of history as their motifs? Can we retrospectively speak of Black artistic movements in France? And how might we account for the lived experience of these artists—often marked by exclusion and condemned to “transcend the limits of both success and failure” (Mildred Thompson)—in the writing of this art history?

The ambition of the exhibition is neither to subsume these artistic practices into a French narrative nor to assign them to exclusive cultural identities—let alone to unify historically distinct identities.

The ambition of the exhibition is neither to subsume these artistic practices into a French narrative nor to assign them to exclusive cultural identities—let alone to unify historically distinct identities. As a cosmopolitan and transhistorical space, one that artists often engage with through academic training, Paris fosters naturally intercultural relationships. Yet these artists were situated within a specific historical context—marked by colonisation and racism, where solidarities emerged—that French art history has thus far largely failed to acknowledge. The exhibition foregrounds their essential contribution to the development of Afro-Atlantic and Pan-African aesthetics, as well as to the enrichment of both French and international art movements.

In doing so, it aligns itself with the legacy of numerous exhibitions and publications that have taken place in the Anglophone world over the past three decades—"Harlem Renaissance: Art of Black America" (1994), "The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-war Britain" (1989), "The Short Century" (2001), "Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power" (2017), "Afro-Atlantic Histories" (2022), "Post-war: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965" (2022)—and draws upon the critical theories of Paul Gilroy, Kobena Mercer, and Henry Louis Gates, as well as the remarkable contributions to art history by curators and scholars such as Lowery Stokes Sims, Valerie Mercer, and Manthia Diawara.

The exhibition adopts a cartographic and historiographic approach in order to highlight a wide range of visual artists whose migration to Paris fostered a form of internationalism largely omitted from twentieth-century art historical narratives.

The exhibition adopts a cartographic and historiographic approach in order to highlight a wide range of visual artists whose migration to Paris fostered a form of internationalism largely omitted from twentieth-century art historical narratives. Through its panoramic scope, the exhibition seeks to spark both patrimonial and scholarly awareness, urging French museums and academic institutions to collect, study, and publish on these artists—especially given that most of the current research originates in the English-speaking world. Ultimately, the aim is to emphasise the importance of “cultural difference” (see Kobena Mercer) in reinterpreting modernisms, and to bring together contemporary practices that may have intersected, or missed one another, but that nonetheless produced iconographies shaped by shared imaginaries, thus opening up new transnational and intersectional fields of interpretation.

Both modern and contemporary, these artists—engaged in dialogue with international movements—affirm distinct historical and cultural specificities. One of the central ideas that emerges is that of synthesis: “It is a matter of drawing from both traditionality and Westernness, while transcending them in favour of an original and dynamic synthesis”, as advocated by Beninese artist Christian Zohoncon, a figure connected with the association Les Amis de Présence Africaine. The concept of synthesis, as both aesthetic and political foundation, is grounded in the dialogue initiated by colonial history and in the political upheaval born of “the unanimous protest of the humanities”. This shift in perspective, or reversal of abysses, as poetically formulated by Édouard Glissant, constitutes a historical prerequisite for any humanist reconciliation in the second half of the twentieth century.

The exhibition traces the evolution of decolonisation across the Pan-African and transatlantic space—from the Algerian War and the “Year of Africa” (1960), the civil rights and anti-apartheid movements, “May 68” and Antillean independence struggles, to the exiles prompted by authoritarian regimes in Haiti, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic, and the fight against racism and for equality in late twentieth-century France. This political backdrop at times forms a direct framework for certain artistic practices, while in parallel, solitary visual experimentations—brought into aesthetic community through the exhibition—emerge and unfold.

The exhibition traces the evolution of decolonisation across the Pan-African and transatlantic space—from the Algerian War and the “Year of Africa” (1960), the civil rights and anti-apartheid movements, “May 68” and Antillean independence struggles, to the exiles prompted by authoritarian regimes in Haiti, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic, and the fight against racism and for equality in late twentieth-century France.

At the centre of the exhibition, a circular matrix echoes the motif of the Black Atlantic—an ocean turned record—a metonym for the Caribbean and Édouard Glissant’s Tout-Monde (1993), reimagined here as a representation of the Parisian space. It proposes a new universalism drawn “from all differences”. Glissant was the first to propose the concept of relation, which can be applied to the artists’ attachment to Paris—not so much to a nation-state as to a café-based “Internationale”: more than a geographical site, the capital offers a diasporic experience of encounter. At once a place and a non-place, the poet Ted Joans’ “nest” transforms Paris into a crucible for a relational methodology, “where people had the chance to come and admire artworks, have a coffee or a drink, attend poetry readings”—to borrow the words of Jamaican artist Karl Parboosingh, a student of Fernand Léger in the 1950s.

When applied to Afro-modern practices, the Parisian space becomes a tool for challenging both aesthetic and political genealogies—“bearing and emerging equally from the scar of radicalisation and the ‘diasporic’ effects of modernity”, as Grégory Pierrot suggests in his analysis of Afro-Surrealist forms. Paris fosters assemblage and relationality, generating a space of mutual accommodation that invites artists to adopt a postmodern and critical gaze, even as they learn the very tools of modernity. Freed from a linear and progressive art historical narrative, “the postmodern African artist was a kind of double agent who had to enter the Western melody while engaging in a form of espionage, using their secrets to advance art in Africa” (see Pfunzo Sidogi and Bongi Dhlomo, Mihloti ya ntsako, Journeys with the Bongi Dhlomo Collection, 2022).

In parallel with this often hidden and transnational rewriting of art history, the exhibition lays out an unfinished cartography of Black Paris, already outlined by Michel Fabre. It includes sites of training (the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs) as well as hubs for the production of Black knowledge (Présence Africaine and Revue Noire), and a multidisciplinary history of Parisian nightlife—from the Left Bank in the 1950s to the Right Bank in the 1980s. From Les Griots theatre company and Théâtre Noir, to the Black New Arts Gallery and the “Cinéma du monde” initiative, decade after decade, an overlooked history of both dedicated and non-aligned spaces unfolds—sites of international alliances systematically excluded from institutional narratives, now brought into view and celebrated. ◼

* retrouvez l'intégralité de ce texte dans le catalogue de l'exposition (éditions du Centre Pompidou)

Related articles

In the calendar

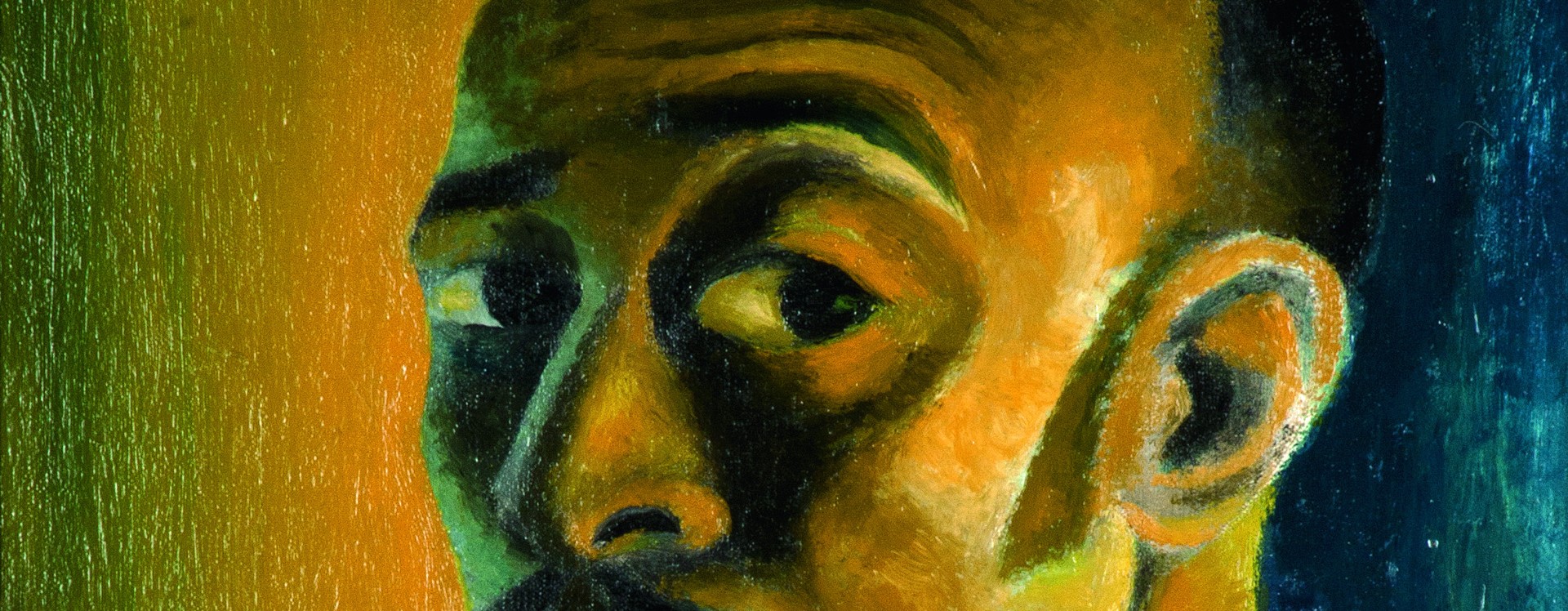

Gerard Sekoto, Self-portrait [Autoportrait], 1947

Huile sur carton, 45,7 × 35,6 cm

The Kilbourn Collection

© Estate of Gerard Sekoto/Adagp, Paris, 2025

Photo © Jacopo Salvi