Eva Nielsen: Where Landscapes Leave Their Mark

Last year, a scientific study of the Mediterranean basin revealed a troubling truth: by 2100, a quarter of the Camargue will be under water due to climate change. The effects are already visible in this French region shaped by the Rhône delta, known for its rose-tinted salt marshes, where 25% of the land lies below sea level. This evolving land first caught the attention of Eva Nielsen a few years ago, as she prepared a project for the BMW Art Makers programme. For the past three years, it has never left the mind of the French artist, nominated this year for the Marcel Duchamp Prize.

Both fascinated by its erosion and alarmed by its programmed disappearance, the artist has been exploring the Camargue through works that combine photography and painting. A first selection was unveiled at the Rencontres d’Arles in summer 2023. In these pieces, a play on transparency and layering extends the formal principles she had already begun developing in her enigmatic, hybrid landscapes of floating architectures against twilight skies — compositions she has been creating on canvas since the late 2000s.

What I loved about analogue photography was retinal persistence, shot and reverse shot, alchemy. But above all, the idea of making something appear.

Eva Nielsen

Nielsen now admits it without hesitation: when she set out on her artistic path twenty years ago, she wanted to be “anything but a painter”. Deeply curious about her surroundings, the Paris suburban native first turned to analogue photography as a way of capturing the landscapes she observed from the windows of the RER: formerly rural zones that had been rapidly urbanised since her birth in the early 1980s. As a teenager, armed with her camera, she roamed the peripheries of a burgeoning Grand Paris—between construction sites and abandoned buildings — committing them to film. “What I loved about analogue photography was retinal persistence, shot and reverse shot, alchemy”, she recalls. “But above all, the idea of making something appear.”

I realised very early on that my practice needed to be hybrid, like the spaces I’d been moving through since childhood. Screen printing immediately felt like the obvious choice: it was the perfect combination of painting and photography.

Eva Nielsen

Her fascination with printing techniques led to a discovery during her studies at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris that would prove decisive: screen printing. “I realised very early on that my practice needed to be hybrid, like the spaces I’d been moving through since childhood. Screen printing immediately felt like the obvious choice: it was the perfect combination of painting and photography.”

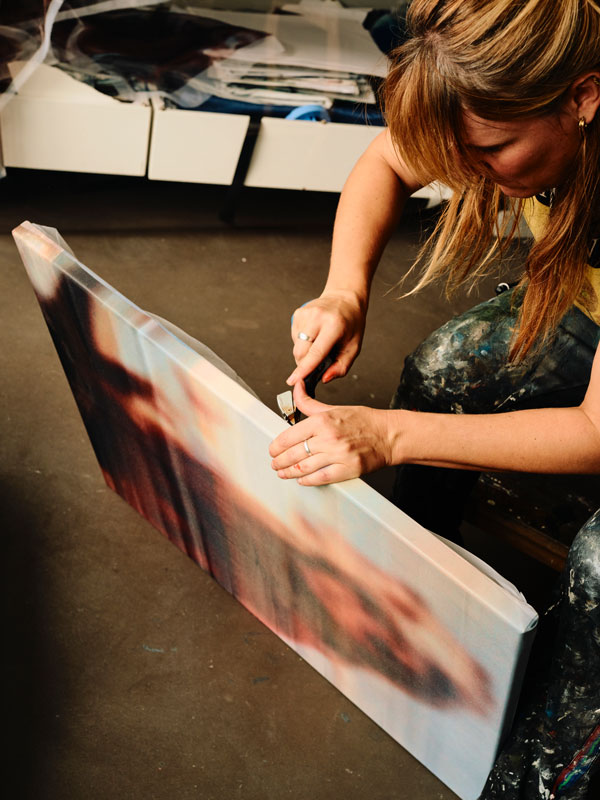

In the school’s dedicated workshop, alongside fellow student Raphaël Barontini, Nielsen embraced the technique in an experimental way. First, on Photoshop, she created collages from her own photographs, layering images to “stratify [her] gaze and recompose it on the canvas through screen printing.” Then, on sometimes large formats, she built up black-and-white architectural forms, stencil by stencil, which she later masked with tape to paint the untouched areas in oil.

Her most emblematic works bear this signature composition: in the foreground, a greyscale architectural fragment set against a vividly coloured natural backdrop.

Eva Nielsen

Her most emblematic works bear this signature composition: in the foreground, a greyscale architectural fragment—brutalist structure, spiral staircase, gate or railing—set against a vividly coloured natural backdrop, horizon line and sky painted from her photographs.

“I try to suggest volume, to sculpt the negative space, but in two dimensions”, Nielsen explains in her studio in Paris’s 13th arrondissement. Inspired by sculptors Robert Rauschenberg and Barbara Hepworth as well as painter Georgia O’Keeffe, she emphasises her attraction to the materiality the medium affords. “Screen printing preserves the painting’s graininess. The transparencies we burn also act as a screen, a sieve.” For nearly fifteen years she worked in a highly artisanal way, exposing screens with garden lamps, before recently acquiring a professional machine.

Even though I prepare my compositions with great care, the interstices remain. The edges between screens, the differences in inking… These create texture, nuance, and a striking strangeness that, for me, resonates with human experience.

Eva Nielsen

She reminds us that screen printing is a physical practice, one that engages the whole body—just as when she paints, often with the canvas spread on the floor. “At a certain point, I can’t tell where my studio floor ends and my painting or my legs begin. It’s as if I’m wading through my own works”, she laughs, likening her workspace to the marshes that inspire her. On her canvases—ranging from small formats to two or three metres high and wide—she doesn’t hesitate to leave imperfections visible. "Even though I prepare my compositions with great care, the interstices remain. The edges between screens, the differences in inking… These create texture, nuance, and a striking strangeness that, for me, resonates with human experience.”

From the mountains of the Vercors to Iceland’s volcanoes, Nielsen loves to travel and photograph raw nature. Yet the works that emerge from these images are far from topographical. Instead, they draw us into indeterminate landscapes whose components resist localisation. “We’re always on the edge of the city and at the limits of the visible, in a zone of uncertainty”, she sums up. These enigmatic, almost dreamlike spaces may evoke Escher’s impossible architectures, Giorgio de Chirico’s metaphysical vistas, or the lost horizons painted by Kay Sage. But Nielsen’s use of photography and screen printing lends them a destabilising, unsettling realism, even a trompe-l’œil effect.

From the mountains of the Vercors to Iceland’s volcanoes, Nielsen loves to travel and photograph raw nature.

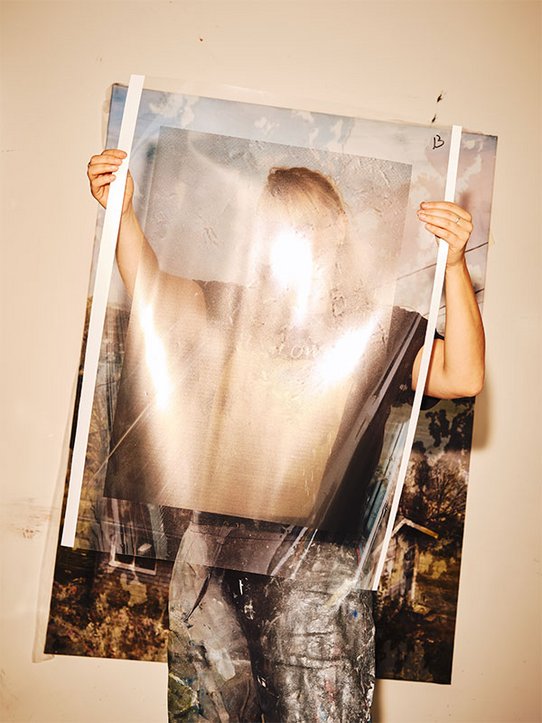

In recent years, she has discreetly introduced the human figure, using family archive photos printed on silk organza or latex stretched across the painted canvas. The superimposed fabric produces textural effects, vibrations and transparencies that give these figures a spectral aura, echoing the artist’s central obsessions: “seeing through” and “bringing to the surface”.

For the 25th edition of the Marcel Duchamp Prize, presented for the first time at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, Nielsen unveils Rift—a geological term describing the rupture that leads to the formation of a tectonic fault. Occupying an entire room, her project synthesises her explorations: beyond two large-scale canvases, she materialises the idea of “sedimentation”, of layers and depth, using metal structures to suspend smaller works that “appear like echoes, like resurfacing memories”.

The work stamps the landscape, the landscape stamps the work… and, while revealing its extraordinary character, it alerts viewers to the urgency of its preservation.

Parts of these new pieces were created during her recent return to the Camargue, where she pushed the fusion between image and nature further. “In front of these salt marshes, I truly felt as though I were standing in front of photographic baths in the darkroom.” To materialise this analogy, she brought her printed transparencies with her and immersed them in the marshes to be photographed, letting the films float in the clear water and emerge marked by natural deposits. The work stamps the landscape, the landscape stamps the work… and, while revealing its extraordinary character, it alerts viewers to the urgency of its preservation. ◼