Flying Saucer, Giant Egg… The Centre Pompidous You Never Got to See!

When the major architectural competition for the « Plateau Beaubourg » was launched at the end of 1970, President Georges Pompidou was clear: emerging talents from around the world needed to be able to submit their work. The competition was not to be reserved for large, established firms.

In 1971, more than 681 entries poured in from across the globe—from Argentina to Japan, via the United States—judged by a panel chaired by the renowned architect and designer Jean Prouvé. Whimsical, unbuildable, poetic, captivating, or even completely off the mark, these alternative proposals for the Centre Pompidou reveal the deep tensions running through architecture in the 1970s.

Whimsical, unbuildable, poetic, captivating, or even completely off the mark, these alternative proposals for the Centre Pompidou reveal the deep tensions running through architecture in the 1970s.

To discover some of these “losing” projects, head to the Académie d’architecture in Paris for the exhibition “Concours Beaubourg 1971. Une mutation de l’architecture”. Featuring around a hundred previously unseen archival materials—drawings, photographs, models, and more—the exhibition, co-produced by the Académie d’architecture and the Centre Pompidou (with support from the École nationale supérieure d’architecture de Saint-Étienne), presents some forty projects submitted to the competition, along with original drawings from the Académie’s archives. It also shows how the winning young team challenged not only the classical model of cultural institutions in Paris, but the very role of the architect—bringing together a multidisciplinary team that fused architecture, engineering, construction, and high technology, in the spirit of so-called “Total Design”.

We take a look back at some of these spectacular yet unselected projects with Boris Hamzeian of the Centre Pompidou’s architecture department. He is co-curator of the exhibition (with Pieter Uyttenhove), teaches at ENSASE, and is the author of several key works on the architecture of the Centre Pompidou.

The Project

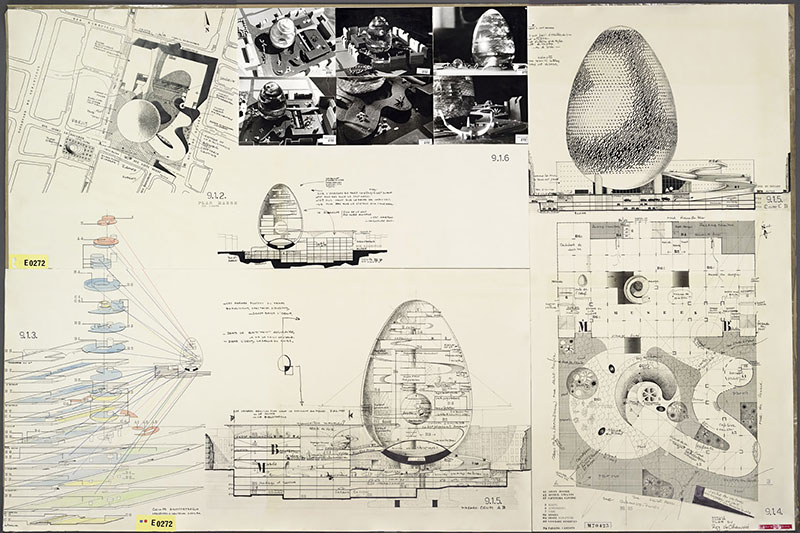

A giant egg, perched on a three-storey base.

The Influences

So—was it the chicken or the egg? This much is clear: the egg didn’t come first at the Beaubourg competition. A truly unclassifiable figure, architect and designer André Bruyère (1912–1998) always had a soft spot for the ovoid. For him, the shell contained every curve within it; its perfect shape—neither feminine nor masculine—was a philosophically unassailable object.

The Backstory

The jury had stated that it ruled out entries driven by grand architectural “gestures” that overlooked urban concerns. And yet, Bruyère’s egg—undeniably a part of that category—seems to have received special treatment from Jean Prouvé, the jury president (and a past collaborator of Bruyère’s on similar projects), who saw to it that the proposal made it through to the second round of deliberations. Though rejected for Beaubourg, the ovoid tower would resurface in Bruyère’s submissions to other competitions—in New York, Hong Kong, and Marseille’s harbour—none of which bore fruit.

Though rejected for Beaubourg, the ovoid tower would resurface in Bruyère’s submissions to other competitions—in New York, Hong Kong, and Marseille’s harbour—none of which bore fruit.

Historian Boris Hamzeian’s Take

“It’s a rather gratuitous form—one that doesn’t really respond to the brief! What’s interesting, though, is the technical ambition behind it: he aimed to create a large, uninterrupted interior space. But then he realised he couldn’t fit everything into his egg, so he added a three-storey base and four underground levels to accommodate the full programme.”

The Project

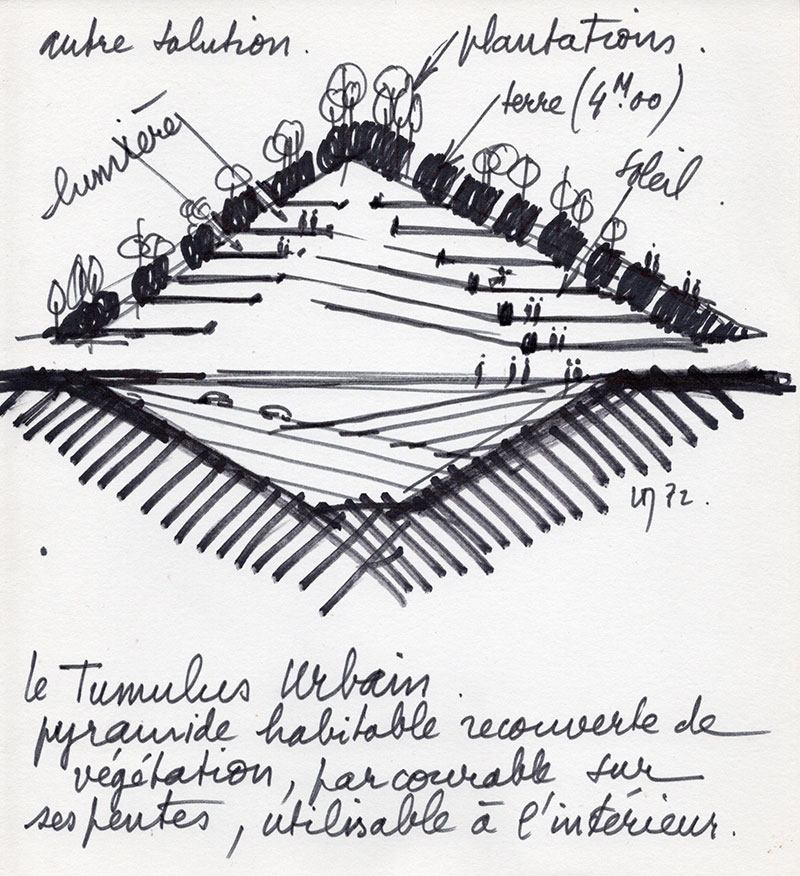

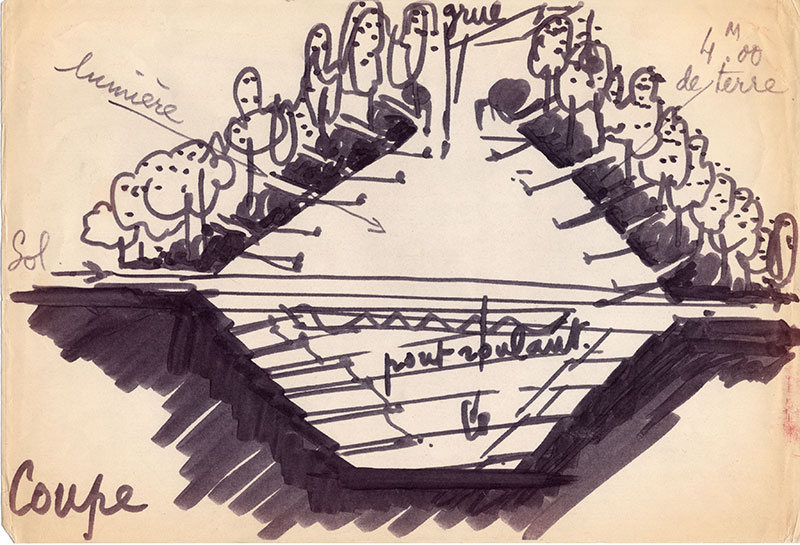

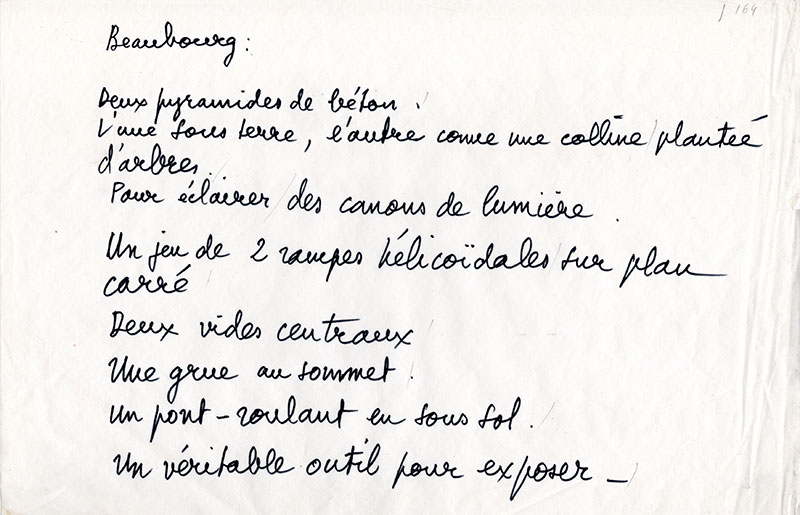

A double pyramid. One, visible and cloaked in dense forest, rises like a funerary tumulus in the heart of Paris. The other is carved into the ground below, a negative imprint echoing its twin above.

The Influences

Claude Parent (1923–2016) is inseparable from his intellectual counterpart, philosopher Paul Virilio. Together, they theorised the “oblique function”—a love letter to sloping surfaces, seen here on the pyramid’s angled faces. They also studied the concrete bunkers of the Atlantic Wall, whose brutalist echoes resonate through this design. The museum becomes a kind of Mesopotamian fortress, at the risk of making this futuristic ziggurat feel more like a tomb than a cultural venue.

Several of Parent’s drawings for the competition were lost due to water damage in the 1980s.

The Backstory

Several of Parent’s drawings for the competition were lost due to water damage in the 1980s. The preparatory sketches presented here come from the architect’s estate archives, allowing us to rediscover a striking project once thought lost.

Historian Boris Hamzeian’s Take

“What a magnificent proposal! It reminds me of the Mausoleum of Augustus in Rome. What’s especially interesting is the presence of vegetation on the pyramid—virtually absent from other competition entries—which would later become a major topic under Valéry Giscard d’Estaing’s presidency.”

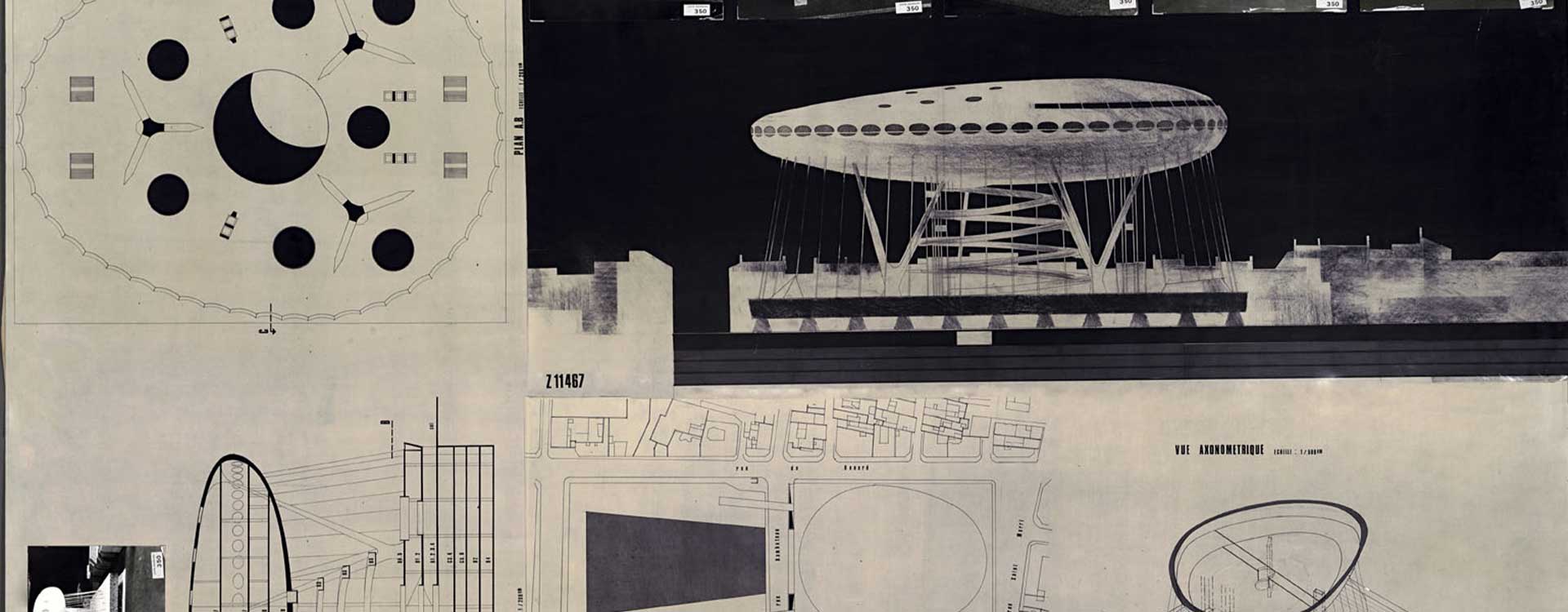

The Project

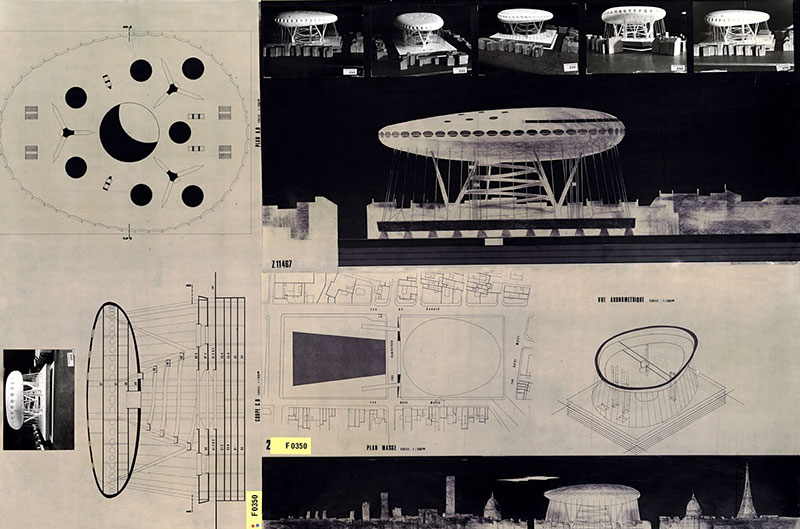

A suspended structure, resting on three pillars, over 50 metres above the ground.

The Influences

The “space age” aesthetic that shaped this project emerged in the 1960s. For about two decades, designers and architects embraced simple geometric forms inspired by rockets and the extraterrestrial technologies of comic books. Ubiquitous in the design output of the time, these shapes are sometimes seen as an ironic, unconscious response to the atomic threat during the Cold War. Luc Zavaroni’s (b. 1942) suspended museum—like a Martian zeppelin—hovers over the City of Light as a joyful, gently otherworldly presence.

The “space age” aesthetic that shaped this project emerged in the 1960s. For about two decades, designers and architects embraced simple geometric forms inspired by rockets and the extraterrestrial technologies of comic books.

The Backstory

Luc Zavaroni trained at the Beaux-Arts in Paris, in the studio of his father, Othello Zavaroni, who taught in a rather conservative academic tradition. This highly utopian project, most likely unfeasible from a structural standpoint, seems to have been submitted primarily as a “paper architecture” concept. The board he submitted barely indicates how the interior space would be organised—despite this being a requirement.

Historian Boris Hamzeian’s Take

“You can see that the axonometric perspective wasn’t coloured in, as the rules required—maybe he ran out of time, which would have been grounds for disqualification. So: no regrets! The jury rejected the project quite quickly, but I find it very endearing. There’s a real sense of youthfulness to it—almost a kind of touching naivety.”

The Project

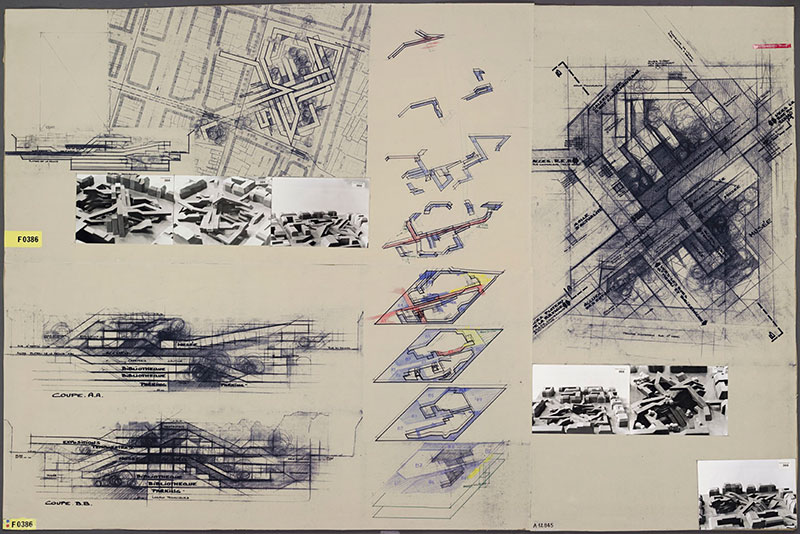

A knot of sprawling, tentacular galleries unfurling across the Beaubourg plateau in every direction—including upwards.

The Influences

The project by Jean Nouvel (b. 1945) and François Seigneur—who would go on to co-found Nouvel’s first architecture practice in 1970—is deliberately provocative. The entire museum is composed of classical-style galleries, like those of the Louvre, but spectacularly distorted in a near-monstrous way. The archetype of the dusty gallery is thoroughly upended. The duo went further than Le Corbusier, who, just a few years earlier, had proposed a “museum without end” made up of a single gallery spiralling infinitely. Here, they imagined a chaotic structure that feels like the missing link between a Möbius strip and an abstract bas-relief.

The Backstory

To quote Rodrigue in Corneille’s Le Cid: “To noble souls, valour cannot wait for years.” A lesson clearly taken to heart by Jean Nouvel, who submitted this project before even graduating as an architect. The boards were drawn by François Seigneur (who was older and already registered with the Order of Architects), but the playful, provocative spirit of Nouvel is unmistakable—qualities he would carry into a prolific career designing museums, from the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris (1987, with Architecture-Studio) to the National Museum of Qatar in Doha (2016).

Historian Boris Hamzeian’s Take

“This was a project that didn’t catch the jury’s attention at all! And yet, it has real qualities that set it apart. Other future architectural heavyweights also applied when they were very young—Rem Koolhaas, for example, submitted a strikingly unconventional project of his own…”

The Project

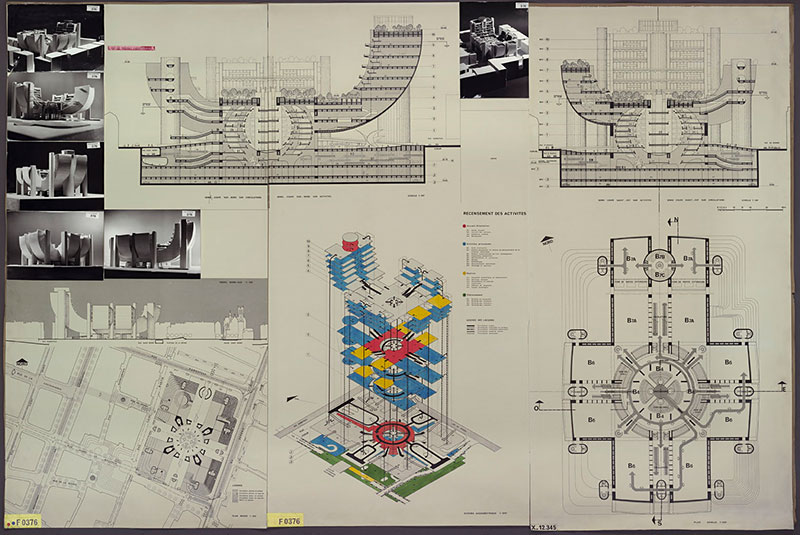

A strikingly bold complex, with two lateral wings—one of which houses the Bibliothèque publique d’information—that opens up space on the main plaza.

The Influences

Founders of the ANPAR agency, Michel Andrault (1926–2020) and Pierre Parat (1928–2019) developed a highly distinctive graphic style throughout the 1970s and 1980s, standing apart from the mainstream output of the time. Their competition entry, formally influenced by the American master Louis Kahn, plays with structural balance in a clever push-and-pull between supports and suspended elements, lending surprising lightness to the whole. Faithfully following the competition’s guidelines, their proposal gave special emphasis to the entrance hall—here reimagined as a monumental sphere that feeds into the rest of the building and already contains exhibition spaces.

The Backstory

Model students—and heads of a major firm at the height of its success—Andrault and Parat went the extra mile by including a circulation diagram in their submission, even though it wasn’t required!

Historian Boris Hamzeian’s Take

“We found an enormous binder full of preparatory drawings for Andrault and Parat’s competition entry. You can trace their entire design thinking through it, including some striking formal variations, before they eventually settled on this two-wing structure!”

The Project

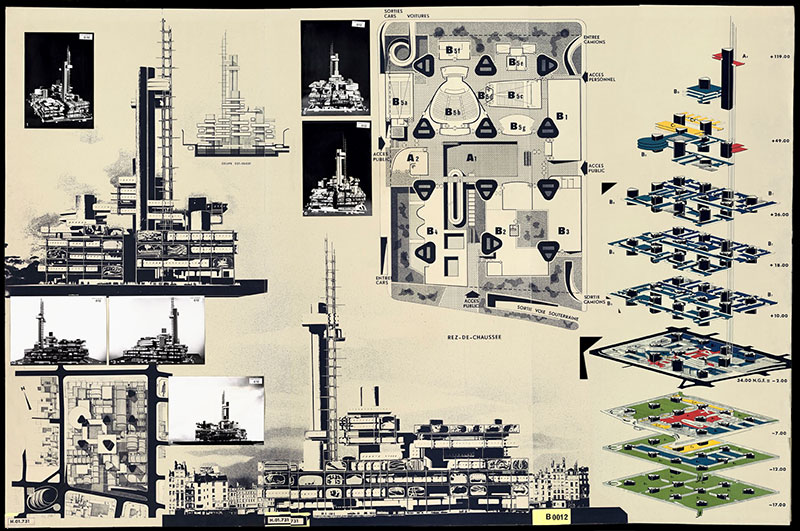

A main metal lattice structure supported by a few tall towers, into which independent modules are slotted. Above it all rises a tower nearly a hundred metres high, designed to house a panoramic restaurant

The Influences

On paper, Henry Pottier’s (1912–2000) submission ticks all the boxes. The metal framework and overall concept recall the Fun Palace, the visionary and unbuilt project by Cedric Price—also a known influence on the winning design. Pottier’s proposal adds a nearly metabolist logic to the scheme, with prefabricated modules whose ends would be decorated by artists. A specialist in high-rise structures, he even includes a panoramic tower that pierces the Parisian “velum,” just as Georges Pompidou had hoped for.

It was well known that President Georges Pompidou was fond of tall buildings. Having a panoramic tower like this, right in the heart of Paris—that was absolutely in line with his personal taste.

Boris Hamzeian, historian

The Backstory

Well-targeted and relevant, Henry Pottier’s project had everything going for it. Yet it was the team led by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers, working with engineers from Arup & Partners, that ultimately won. The designs were so similar that Pottier sent numerous letters to the competition organisers to protest not being selected. Poor sportsmanship—or justified frustration?

Historian Boris Hamzeian’s Take

“It was well known that President Georges Pompidou was fond of tall buildings. He came back enchanted from his travels to Moscow, where he’d seen the Stalinist skyscrapers of the Seven Sisters, and to Manhattan. Having a panoramic tower like this, right in the heart of Paris—that was absolutely in line with his personal taste.” ◼

Related articles

In the calendar

Presentation board for Luc Zavaroni’s Beaubourg project, 1970

© Centre Pompidou Archives