In conversation : Wolfgang Tillmans and Renzo Piano

I always believed in books, because unless each and every copy of their print run is destroyed, they create a physical fact that cannot be undone. They are a record of what was possible, of what was thought and said—of what it was possible to say, at a given time, in a given place.

From its inception, the Centre Pompidou was envisioned as a place for art and books, for culture and books, for community and books, for democratising knowledge. No less than three floors of a total of six have been dedicated to books, magazines, and newspapers, the printed evidence of our cultural existence. That shows no little trust and faith on the part of the Centre Pompidou’s founders in the printed word and, may I say, the printed image.

The printed page has played a crucial role in my life and practice. I have always found it to be a tangible and accessible medium for engaging with the work of other artists, as well as an impactful way to show my own pictures and share them with a wider audience.

Wolfgang Tillmans

The printed page has played a crucial role in my life and practice. I have always found it to be a tangible and accessible medium for engaging with the work of other artists, as well as an impactful way to show my own pictures and share them with a wider audience. In addition to contributing numerous portfolios to magazines, I have designed and edited over thirty books, and I have consistently sought innovative ways to incorporate books and printed matter into my exhibitions, creating custom tables and display furniture, as I have done for this exhibition.

Aside from their civilisational significance, books are sensual objects, a pleasure to hold, to weigh, to smell, to live with. They are a point of connection, a bridge to other human beings.

Similarly, I have viewed making photographs as a way of building a connection to other fellow humans across time and space. There is a tangible intimacy in these media objects, a physicality that evokes memory and emotions. Do you know this feeling? Have you seen things like this before as well? Can you sense the smell that might be present here in this photograph? The touch. The feel. The sensation. The memory?

For all this open-access richness, we celebrate the Bibliothèque Publique d’Information (Bpi) and the knowledge that it preserves and promotes—a testament to the principles of inclusivity and education. Haji Bektash Veli, the thirteenth-century Islamic scholar and mystic, famously said that “the end of a path not guided by knowledge is darkness.” So, let’s agree that knowledge is what we should strive for, because darkness exists by default and in abundance.

Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers were tasked with creating a space for culture and knowledge, and being still young at the time, they embarked on a task they were not fully equipped for—a true challenge for them and for the city. But as Piano explained to me in a brief conversation, they were trusted by the establishment from the top down to create a vision rooted in the idea of freedom. And trust, coupled with freedom, can go a long way.

This vision is as exhilarating today as it was in 1977. I can’t even imagine what the building must have felt like to a person born in 1910, standing, at the age of sixty-seven, in front of this machine of culture, which looks like a usine (factory). And yet, almost fifty years after its completion and despite its slight impracticality, it still evokes gasps of admiration for its audacity.

I can’t even imagine what the building must have felt like to a person born in 1910, standing, at the age of sixty-seven, in front of this machine of culture, which looks like a factory.

Wolfgang Tillmans

The Bpi—the most silent, under-the-radar aspect of the Centre Pompidou—has been home to probably hundreds of thousands, maybe millions of visitors who have written their dissertations, researched their baccalaureates, or spent their afternoons getting warm and benefiting from the shelter the building provides. In the preceding thirty years, during my many visits to Paris and to the Centre Pompidou, I hadn’t paid much attention to the BPI. I would go up the escalator past the third floor to access the modern and contemporary art galleries. For the past two years, however, I have felt honoured to be introduced to the marvel of the second and third floors—it is perhaps the only institution of its kind that doesn’t require a reader’s card: anyone can come and use its facilities. And its success is evident and acts as a beacon. Not only is it a well-intentioned idea but it has proven its usefulness and purpose. It shouldn’t need defending, and yet I feel at this point in 2025 it is appropriate to reassert the consensus that the existence of this place, the Bpi, is a good thing, a truly democratic phenomenon.

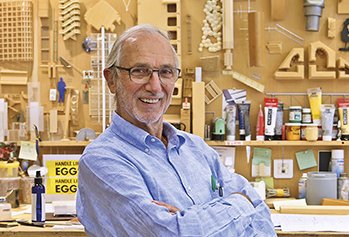

Realising that the offices of one of the two architects who designed the building is only a stone’s throw away in Rue des Archives, I inquired if I could meet him, take his portrait, and ask him a few questions. The ensuing meeting with Renzo Piano lasted no more than an hour in a busy midweek for both of us, yet it was a touching and illuminating encounter in which I was able to get a better sense of the ambition and vision that brought this building into being.

Wolfgang Tillmans – I would like to take a portrait of you and ask you some questions. I’m really excited to meet you because I’ll be exhibiting at the Centre Pompidou.

Renzo Piano – Where will you put the exhibit in the Centre?

WT – On the deuxième étage, in the Bpi, the bibliothèque. So, it’s a very unique proposition.

RP – Very nice, I will go and see it. Do you already know where you want to take the picture?

WT – I’d like to do it outside on the street, where you can see the Pompidou at the end of the road.

RP – Ah yes, that’s what I see every day. I pass by four times a day.

WT – [laughs] And what do you think about it now, almost forty-seven years after its completion?

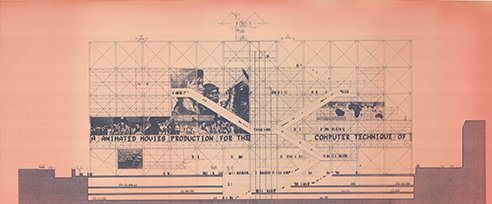

RP – Every time I see the building, I always think that I’m not surprised that we did that with Richard Rogers. We were young bad boys. It was only a couple of years after May ’68, which we didn’t experience as we were living in London. But we did experience London at the time, which was similar. It was all about freedom and protest. I understand why we did it, but it’s less clear to me how they could let us do something like that, because it was incredibly different from everything else.

WT – Yes.

RP – I’m saying this because the politicians in this country were very brave. Everything started with André Malraux, in the sixties. He was the minister of culture and wanted to build maisons de la culture, houses of culture in every city in France—small, medium, and large. They were conceived as places where all the different arts—painting, sculpture, cinema, photography, music, literature—came together. He was that kind of person. After May ’68, a number of people came to the fore in this context, including Georges Pompidou and his wife, Claude. I think the atmosphere in France was conducive to such a miracle. They were very brave because they held an open competition. That’s act of bravery number one. Act of bravery number two: they assembled an incredible jury, with Jean Prouvé, who was not even an architect, and then there was Niemeyer and so many others. And when you put together a jury like this, it’s what they call in France incontournable, which means that if they say something, it cannot really be questioned.

WT – Ah, because it’s so high-powered?

RP – Yes. That was very important. When you put together a jury like this, you have to accept its verdict, for sure. So, you have an open competition, and you introduce this idea of maison de la culture. Also, it was very brave to call Pierre Boulez back from New York. He wasn’t in France anymore, and they wanted to have him back, so they offered to create good working conditions for him as well.

WT – So Ircam [the Institute for Research and Coordination in Acoustics/Music] was part of the original plan?

RP – Yes, it was one of the objectives. It was very ambitious. And they defended it courageously. Because they were attacked by everybody. You know, my school was the Milan Politecnico, but my life was all about occupying the university. I grew up in that atmosphere: protests, occupations, the beautiful and mad idea of changing the world, to create a better one.

I grew up in that atmosphere: protests, occupations, the beautiful and mad idea of changing the world, to create a better one.

Renzo Piano

WT – And the patience to live with the problems that the building created for fifty years.

RP – Our client got hit by seven legal actions to stop, including two that came from architects. They founded a group called Le Geste architectural, and said, “You can’t do all these horrible things in the middle of Paris.” Others argued that the competition was not correct because Prouvé wasn’t even an architect. You know, every sort of excuse. We were under attack, legally, and public opinion was also against us. It was not easy. But we were very young and full of energy.

RP – I want to tell you about how Mr Honda came to the site one day, in 1975 maybe—Mr Honda himself.

WT – Honda?

RP – Honda, the Japanese guy who made the …

WT – … the motorbikes?

RP – Yes. At some point, he looked at me and said: “I like this building, it looks like a motorcycle.” [laughs]

WT – Really? Because he could see the energy.

RP – Exactly. You know, I love to build. I don’t like the separation between architecture and engineering and construction. You have to make a building solid, resistant, and long-lasting. But you have to make it so that even a child understands how it works. And that’s the secret. You need to understand.

WT – I’ve never understood how in architecture, where there are so many details that need to be specified, one person can stay on top of this—which you obviously can’t, but in the end, it carries your name. How do you learn to trust all the people that work for you? Like all the door handles, every fixture, all this decision-making.

RP – I stick my nose into everything. For a normal building, we produce five or six thousand drawings. You have to do everything. But it’s not impossible. I grew up in a family of builders. When I was a young boy, I used to spend a lot of time on building sites with my father, watching. There I learned that you need to spend the right amount of time on things, which means working a lot. The builder must know everything, otherwise the costs go up. It’s a mix of very pragmatic things and very poetic, emotional things. There is a lot of technology in our profession, but a lot of poetry as well. And, by the way, a lot of ethics and humanism.

WT – Yes.

RP – You need to be a builder, but at the same time, you need to be a humanist. You make a place for people. You don’t build a wall, you build bridges. Metaphorical and real ones. I love making bridges by the way. And emotional ones, because you create a space of beauty, for beauty.

You need to be a builder, but at the same time, you need to be a humanist. You make a place for people. You don’t build a wall, you build bridges. Metaphorical and real ones. I love making bridges by the way. And emotional ones, because you create a space of beauty, for beauty.

Renzo Piano

WT – In 2017, I had a solo exhibition at Fondation Beyeler. It is one of my favourite exhibitions, I always say it was the most beautiful space to exhibit in. And it got me curious: you seem to understand light very well.

RP – Light …

WT – I was recently in Fort Worth, at the Kimbell Art Museum, and I was fascinated by the skylight, and then I learned that you were working for Louis Kahn in the late 1960s.

RP – Yes, yes.

WT – Did you have anything to do with the original Kimbell Museum building?

RP – No. I was involved with additions that were made.

WT – But much later.

RP – Yes, much later, only ten years ago. At the time I was working with Kahn on something else, in Harrisburg, but it was about light. He was building a factory for Olivetti-Underwood.

WT – In Harrisburg?

RP – Yes. And the office was in Philadelphia, on Walnut Street. I was a younger architect—it was 1967, 1968, something like that. The structure was already done. The factory had a big plan, so to bring light inside, they left a square open. But then they were in trouble, they didn’t know how to proceed. And one day, when I was assisting Robert Le Ricolais at Penn University, he said to me, “Come with me, we’ll have tea with Louis Kahn in my house on campus.” So we went there, and Kahn told Le Ricolais: “I’m in trouble, I don’t know how to do those elements that bring light inside.” Le Ricolais replied: “Ask this guy, this young guy. He knows how to do that.” I was just an assistant, I was, I don’t know, twenty-eight, twenty-nine. Anyway, Kahn invited me to the office. I had been working there for three or four days, finding a solution, drawing, and one morning, Kahn came by. He saw the drawing and he looked at me and said, “Hm, call me Lou.”

Exhibiting in different museums, I noticed that architects know surprisingly little about light. They often put skylights in rooms that have no effect on the walls whatsoever.

Wolfgang Tillmans

WT – Really? [laughs]

RP – [laughs] And I told him, “Call me Renzo.” Which meant, “Let’s become friends.” And so I started there, and it was all about light.

WT – Exhibiting in different museums, I noticed that architects know surprisingly little about light. They often put skylights in rooms that have no effect on the walls whatsoever. And in many cases, they get permanently covered later. They’re just thought of as an idea that is nice to talk about but is not well conceived.

RP – It’s difficult to say where my interest in light came from. Maybe it’s because of the Mediterranean. I was born in Genoa and grew up there. Genoa is a city of light—it’s on the Mediterranean. And one of the values of the Mediterranean is light, vibration. I’ve always felt, without thinking about it, that light is probably the most important material in architecture. It’s the most immaterial but it’s probably the most important, it’s about transparency, about multiple planes …

[Ernst] Beyeler knew the Menil Collection complex, which I built in Houston. So, he called me and came here, and we started to talk. We wanted to work on light, in an almost metaphysical sense. Light in my work has a fundamental function, not just for museums but also for other buildings. Many clients don’t really understand this. Except for people like Beyeler: he knew what he wanted. As did Dominique de Menil. When I saw her here in Paris, she called me into her flat, somewhere on Rue Saint-Dominique, she looked at me and said, in French, “Monsieur Piano, I want you to design a museum that is small outside and big inside.” A very short brief.

WT – Yes, that’s good. Because often people want the outside to be impressive.

RP – And then that was specifically about light. Because she wanted a building that’s modest outside. Small, modest, not humble but sober. But she wanted the museum to breathe and to feel big when you come in. And that was about light! Light has that magic. It’s also very important emotionally. Not just in museums, but in all buildings, hospitals, office buildings … Light is one of the sensations that define human beings … It may be flat, it may be scattered … There is this famous Japanese concept komorebi, which denotes the emotion of light filtering through the leaves of trees. That’s an ideogram, you see. And when you think about that, komorebi is when you make a space where you have leaves in the trees that appear only in the springtime, and they grow for the summer. Sometimes, they become like a roof or a ceiling, and the light comes through. Then in the autumn they go away, so light comes inside, because it needs light in the winter. All those things have to do with light.

WT – For my show at the Pompidou, I have studied the space a great deal over the last year and a half, and I noticed that one of the fundamental qualities of the floor is, of course, that there are no columns, no pillars. But I also learned that you can only achieve a ceiling with this span if you make it thicker, if you strengthen the support beam. What is the beam called, the zigzag?

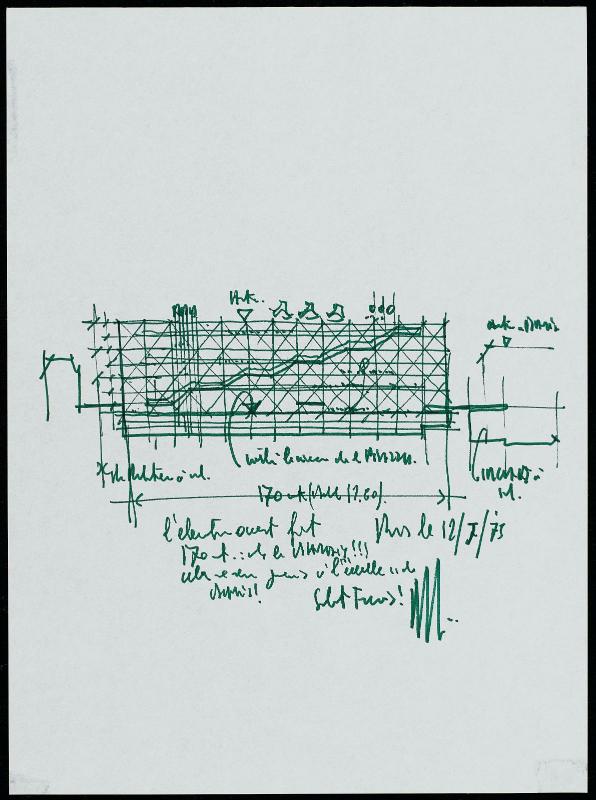

RP – That kind of beam is called the gerberette, or the Gerber beam, after Heinrich Gerber. It’s done like this [draws]. And then here [continues drawing] we have the tension.

WT – Ah, that’s for the tension!

RP – So, there is compression and tension. This goes down, and this goes up. It’s like a balance [draws].

WT – Yes.

RP – And that’s fifty metres. And if you do this for fifty metres, you need something like that [draws]. Otherwise, it becomes too big. And then this was left there.

WT – It’s beautiful.

RP – Ah, it’s beautiful, it shows the muscles.

WT – But it also lowers the usable height in the room extremely. Do you hate it when people build taller in between the beams and obscure them?

RP – Yes. But that building will still be there in five hundred years. It will survive.

WT – In the museum on the fourth and fifth floors, they built these boxes. It looks kinda crazy.

RP – You know, that’s life for a building. It’s also the price we have to pay for total freedom and total flexibility.

WT – But what is your suggestion on how to show very large pictures? The Gerber beams lower the usable height in the rooms significantly—it comes down to three metres fifty, and, for example, I have a picture that is four metres high that I want to show in the exhibition.

RP – Suspend them from the ceiling. This was our [Richard Rogers’s and my] dream from the beginning. Not using walls but panels, without touching the floor.

WT – No gravity.

RP – Yes. Zero gravity.

WT – And is there a suspension system in the ceiling?

RP – Of course, everything is there. That building is a machine. Even the air-conditioning is designed like in a machine.

WT – In the beginning, when it was opened, were paintings really suspended in space? Or did they start building walls?

RP – We did [suspend them]. We did it with Pontus Hultén. We were all free thinkers at that time: Pierre Boulez, for music, Pontus Hultén for art and painting, Jean-Pierre Seguin for the library, which was the first library with open stacks.

WT – Where everybody could just take the book they wanted.

RP – Yes. Freedom was very important. I have a story to tell you. In 2000, we put on an exhibition of the work of the office at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, which was designed by Mies van der Rohe. The span is such that, during the day when everything is hot, the roof comes down, because of the dilatation. In the evening, when the sun sets and everything becomes cold, the roof goes up.

WT – Wow.

RP – Yes, that’s beautiful. So, Mies van der Rohe designed that building—the top floor that you see from Potsdamer Strasse. He made the first exhibition with suspended walls.

WT – Ah, really, so they were hovering five or six centimetres above the floor.

RP – Something like that. So, when we did it ourselves, we did the exhibition with tables. And the tables were floating; they were held by cables. During the day they were a bit lower, at night a bit higher. This idea of suspension is wonderful because it adds something magical.

WT – When I was invited by Laurent Le Bon to do the project, it was clear to me that I wanted to work from the ceiling because it seemed logical. But nobody really wants to touch the ceiling.

RP – When does the exhibition open?

WT – It opens in June next year. It’s the last project. The whole building will be closed, and only my exhibition will be open, until September. It will be the only thing, and I’m closing down the whole building.

RP – Surviving! ◼

*Excerpt from the exhibition catalogue « Nothing could have prepared us – Everything could have prepared us », Spector Books, available online end of August

Related articles

In the calendar

Wolfgang Tillmans, Pompidou CMYK Separation, a, 2024 (detail)

Photo © Wolfgang Tillmans