Architectural Secrets ► The Underbelly of the Centre Pompidou

Spanning five levels and accounting for 48% of the building’s total surface area, the Centre Pompidou’s underground spaces remain largely mysterious — hidden from public view and dedicated in part to functional uses (parking, deliveries, storage) and private areas (workshops, offices).

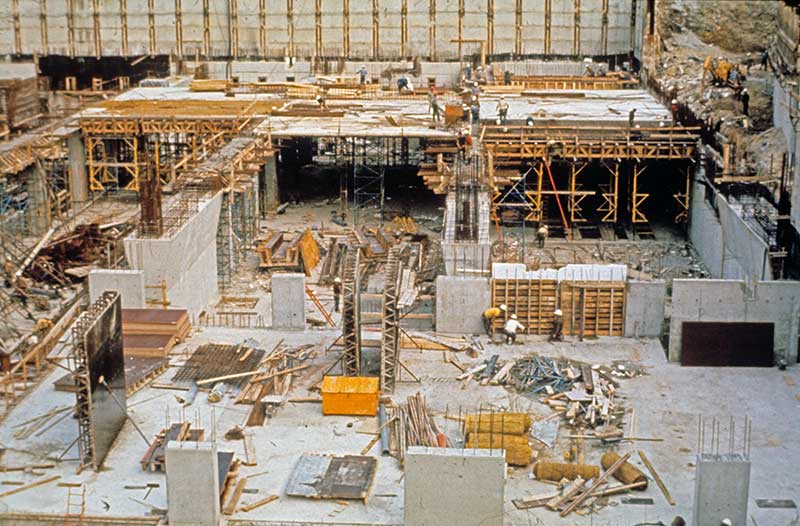

To truly grasp the scope of this subterranean world, the most revealing images are those showing the concrete being poured for the foundations. In 1972, the Beaubourg plateau — home to a large car park since the 1930s — was completely excavated. What became known as le trou de Beaubourg (the Beaubourg hole) reached a depth of sixteen to twenty metres and was reinforced with massive retaining walls. This spectacular chasm appeared around the same time as the infamous trou des Halles (the Halles hole), just a few hundred metres away, on the site of Paris’s historic central market. The proximity of these two monumental excavations sometimes led to confusion among Parisians — and compelled architects Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers to repeatedly clarify in interviews that no buildings were demolished to make way for Beaubourg.

The Centre’s foundations were poured in concrete — a striking contrast to the building’s above-ground architecture, dominated by steel and glass façades. This material choice was a structural necessity: to maintain the tension of the building’s exoskeleton, the steel columns had to be anchored firmly in the ground. To reach for the sky, one must first be grounded.

A City Beneath the City

“Beneath the cobblestones, the beach.” Even better. The underground levels of Beaubourg, stretching beneath the Piazza and the main building, form a city of their own — with inhabitants and their own customs. You’ll find around fifteen specialised workshops, rows of archive shelving, and occupants who’ve long since adapted to the absence of natural light. Nicolas Moreau, lead architect and principal designer for the cultural components of the future Centre Pompidou 2030, shares what he encountered below ground: “In the electromechanics workshop, they repair improbable structures—moving, kinetic, or radio-based. There’s a kind of sedimentation of old posters and objects pinned to the walls; it’s deeply alive. There’s real poetry down there.”

The underground levels of Beaubourg, stretching beneath the Piazza and the main building, form a city of their own — with inhabitants and their own customs.

In the lowest levels lie the machines that keep the building alive — generating heat, cold, converting power, and more. This gently humming machinery, buried like a dragon in the depths of its lair, is the beating heart that sustains the entire Centre. And though hidden from public view, the same colour code used on the building’s exterior applies here: blue for air flow, green for water, yellow for electricity, and so on.

The ultimate feature? A not-so-secret tunnel connects these underground levels to those of the neighbouring Ircam building, completed in 1977, whose main spaces were built underground for acoustic reasons. This passage is all that remains of an ambitious network of tunnels imagined in early versions of the project — a web of underground galleries radiating out across the district.

A Space for Creation

Largely inaccessible, the Centre Pompidou’s underground levels have long been a source of fascination and fantasy. In 1976, under the pseudonym Gustave Affeulpin, sociologist Albert Meister (1927–1982) published La soi-disant Utopie du centre Beaubourg (The So-Called Utopia of the Beaubourg Centre). This irreverent and eccentric manifesto imagines an anarchist utopia “with 0% constraint” nestled beneath the Centre Pompidou — a world of self-management, far from the dreary order of the surface. Affeulpin’s underground squat is a place of creation. As he famously put it: “Above, culture is consumed; here, it’s made.”

In January 2020, artists Christian Boltanski, Jean Kalman and Franck Krawczyk staged Fosse, an opera performed in the museum’s parking garage. Audiences were invited to wander among the musicians in a space lit only by a few car headlights.

Beyond fiction, artists have occasionally been invited to activate these subterranean spaces. One of the most striking interventions is undoubtedly Fosse, the opera by Christian Boltanski, Jean Kalman and Franck Krawczyk, performed in January 2020 in the museum’s parking garage. Spectators of this work for soprano, cello, choir, and amplified ensemble were invited to move freely among the musicians, in a dimly lit space illuminated by headlights — an immersive, dusky concerto unfolding in the depths.

And Tomorrow?

Today, only a small portion of the underground levels is accessible to the public: the atrium (or “pit”) at the heart of the Forum led (until the building’s closure in 2025, ed.) to screening rooms and a photography gallery dedicated to gender, inaugurated in 2014. The architectural firm Moreau Kusunoki, tasked with redesigning the interior spaces ahead of the building’s reopening in 2030, plans to transform parts of these underground areas into fully fledged spaces for exhibitions, performance and creation. These new venues will take the place of oversized parking areas — now largely underused. After all, culture abhors a vacuum! ◼

Related articles

Construction site of the future Piazza of the Centre Pompidou, circa 1972.

Archives © Centre Pompidou

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/9/8/csm_chenille-vignette_braun_ccc5d5c183.jpg)