Le Centre Pompidou &... Woodkid

F

ew French artists enjoy the kind of esteem abroad that Woodkid commands. He is one of the rare exceptions. For nearly a decade, Yoann Lemoine — his given name — has been shaping a deeply personal creative world, one that blends darkness and romanticism, grandeur and intimacy, across both his electronic compositions and his visual work.

After making a name for himself as a music video director — most notably for Drake, Rihanna, and Lana Del Rey (the cult hit Born to Die, 2011) — it was his debut album, The Golden Age, that catapulted him into the spotlight in 2013. Then in his early thirties, the singer-songwriter from Lyon quickly became one of the most sought-after artists of his generation, collaborating across genres and disciplines with figures like Pharrell Williams, Max Richter, JR, and Mylène Farmer. In 2020, he released his ambitious sophomore album, S16. And in 2025, he composed the score for the blockbuster video game Death Stranding 2: On the Beach. A conversation with an artist marked by profound sensitivity.

"When I first arrived in Paris in 2004, I spent a lot of time around the Marais. The Centre Pompidou quickly became an object in my daily landscape. I say object quite deliberately—because that’s truly how I see it: like a giant Lego set down in the middle of Paris. It’s a space that feels playful, visually speaking, and also provocative. The building was widely criticized when it first opened, but it’s an architectural object that asks to be understood. Beaubourg has always been a machine culturelle—had it been a simple white cube, it never would have had the same impact.

The Pompidou is like a giant Lego set down in the middle of Paris. It’s a space that feels playful, visually speaking, and also provocative.

Woodkid

I have a special connection to the Centre Pompidou because, in 2019, I took part in the now-iconic Louis Vuitton show for which Beaubourg’s architecture was reconstructed in the Cour Carrée of the Louvre. It was an idea by Nicolas Ghesquière (artistic director of womenswear), who wanted to mirror two distinctly Parisian forms of architecture—on paper, seemingly at odds, yet in fact deeply complementary. I composed the show’s soundscape, which included music by Rita Mitsouko, Axel Bauer, Jean-Michel Jarre—major figures from the 1980s, the early years of Beaubourg.

I never go to museums alone. I always like to confront my gaze with someone else’s. I come regularly to the Centre Pompidou with friends—it’s a ritual. One exhibition I absolutely loved was the one dedicated to Pierre Paulin. I’m a design enthusiast, with a strong preference for mid-century Italian, American, and French design. I’m a fan of Pierre Jeanneret and Jean Prouvé—both of whom I collect. I also admire Ettore Sottsass, especially his Synthesis period for Olivetti. And I have a deep appreciation for Japanese design too, particularly the work of Kazuhide Takahama.

Another artist who fascinates me is Jean Tinguely. I had the chance to record some of his kinetic works in motion (at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam), and those recordings gave an industrial texture to “Pale Yellow,” a track on my second album, S16.

Just recently, I went to see "Paris noir", and it hit me like a tidal wave of emotion. I hadn’t really known what to expect from such a dense exhibition… At times, I felt a bit ignorant—I came face to face with my own blind spots, with the filters and distortions through which we often view art history. A kind of whitewashing, really. It was a much-needed recalibration. But one thing gave me comfort: the political power of music. Many of the key figures featured in the show were musicians as well.

There’s an incredible tenderness, a gentleness, in Tillmans’s work. His relationship to HIV, his commitment to Europe, his anxiety over the rise of fascism… These are subjects that clearly haunt him, and yet he addresses them with such humanity.

Woodkid

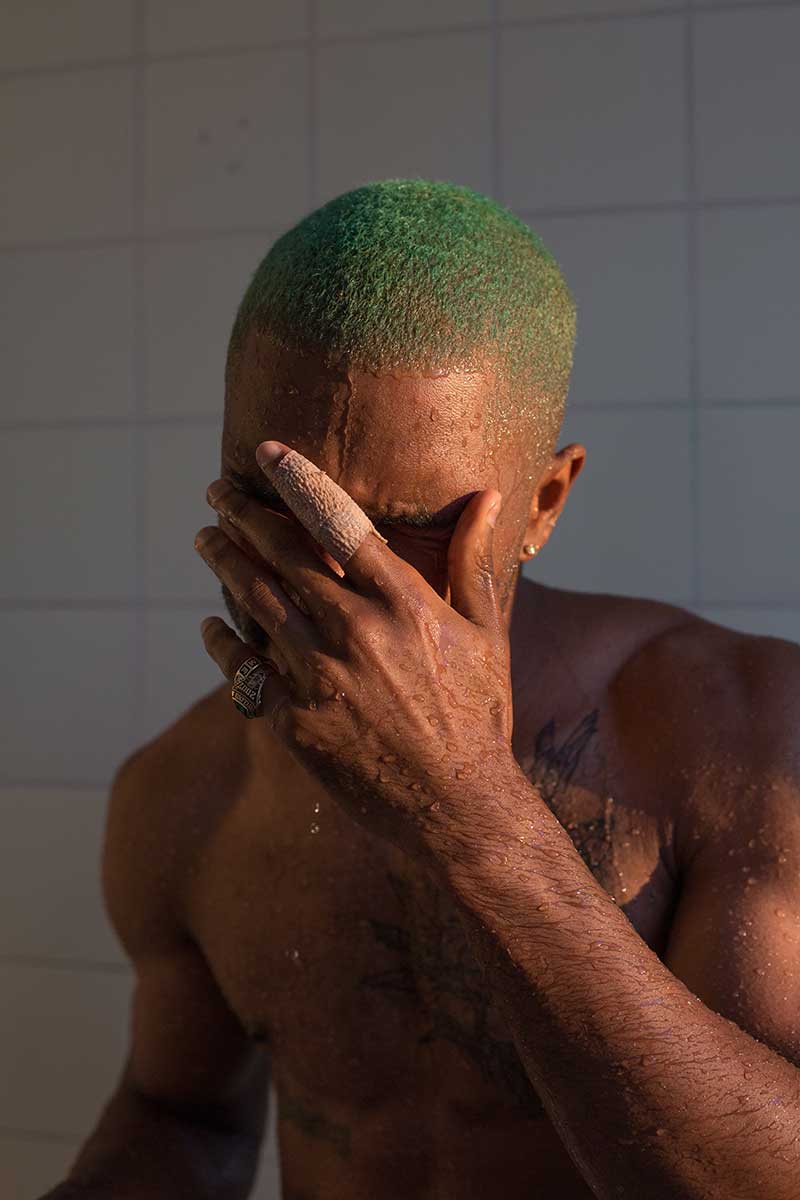

Of course, I also went to see Wolfgang Tillmans’s exhibition. He and I are in regular conversation. In fact, I own one of his photographs—a piece from the series with musician Frank Ocean (whose most well-known portrait appears in the show). I stayed there for a long time, and I loved every bit of it. Everything spoke to me: his interest in formalism and the material qualities of the image, as much as his exploration of the flesh, the emotional, the sensual, the sexual.

Our visual worlds are quite different, but there’s a metaphysical thread that connects us—something intimate. A very particular outlook, a shared way of relating to the world. I feel like we’re both searching for emotion in unexpected places.

What I love about his work is that I sense no cynicism in it whatsoever. There’s an immense tenderness, a gentleness to him. His relationship to HIV, his attachment to Europe, his anxiety over the rise of fascism… These are subjects that clearly weigh on him, and yet he approaches them with such profound humanity.

There are very few people I consider role models—Wolfgang Tillmans is one of them. He possesses a kind of heightened intelligence: sensory, visual, political, social. I understand what he finds beautiful, and some of his photographs feel to me almost like passwords, like secret codes. Tillmans seeks out beauty in the least obvious places—in places where people often refuse to see it. He moves me deeply." ◼

Related articles

In the calendar

Portrait of artist Woodkid

Photo © Fred Gervais