“Le Cyclop”: A monumental odyssey by Niki de Saint Phalle, Jean Tinguely, and their friends

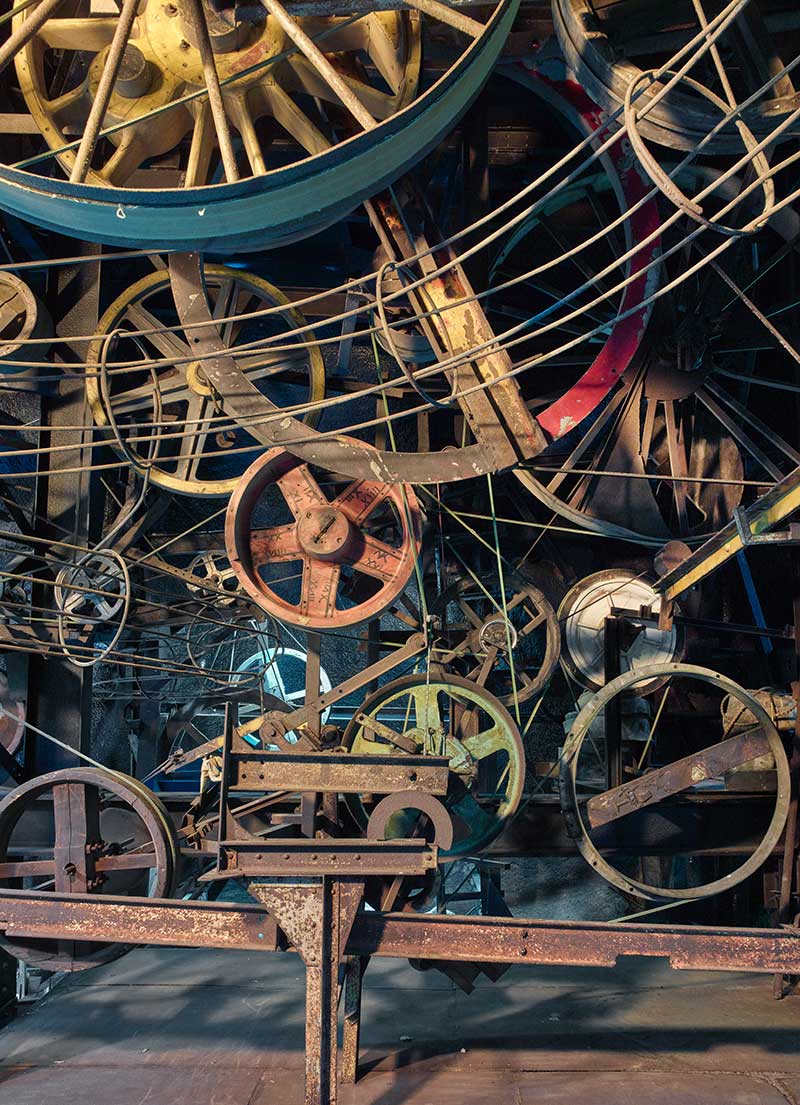

It creaks, groans, and moans—in short, it’s alive. A colossal structure of steel and glass weighing over three hundred tonnes, Le Cyclop is unique. It is a bodiless head, outfitted with a single eye, a solitary ear, and a slide-like tongue. Behind its glittering, mirrored face—conceived by Niki de Saint Phalle—this Dantean creature reveals an infernal machinery of grinding gears, the work of Jean Tinguely. One can even spot a curious pipe strikingly similar to the iconic ducts of the Centre Pompidou façade—legend has it the Swiss artist and his accomplices spirited it away from Beaubourg under cover of night.

On Le Cyclop, one can even spot a curious pipe strikingly similar to the iconic ducts of the Centre Pompidou façade—legend has it the Swiss artist and his accomplices spirited it away from Beaubourg under cover of night.

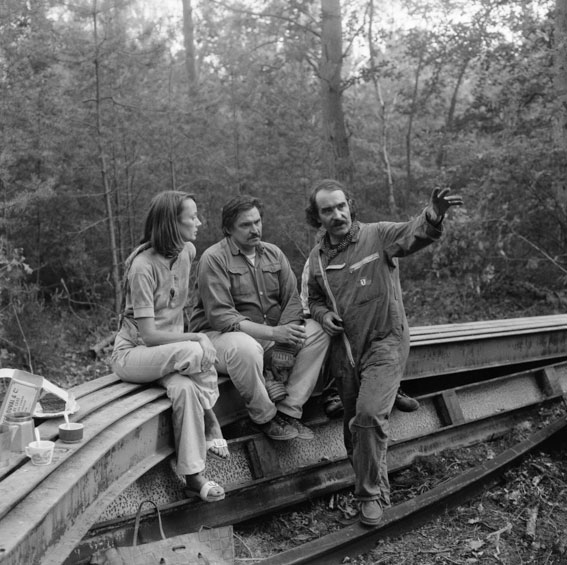

Driven by Tinguely, Le Cyclop was also the vision of many fellow artists and friends, each invited to leave their mark—amongst them, Niki de Saint Phalle, Bernhard Luginbühl, Eva Aeppli, Arman, Jean-Pierre Raynaud, Daniel Spoerri, and Rico Weber. It was a wild, collective adventure, one fraught with setbacks, and one that very nearly never saw the light of day.

Just over forty kilometres south of Paris, Le Cyclop lies hidden in the woods of Milly-la-Forêt, near Fontainebleau (in Essonne). There, rising through the canopy, this scrap-metal giant towers twenty metres above the forest floor. Fully accessible to visitors, it offers an immersive experience—a sequence of surprises blending sound sculptures, kinetic mini-theatres, and an array of influences ranging from art brut and Dada to kinetic art and nouveau réalisme. Initiated in 1969, the construction of Le Cyclop—originally titled La Tête (The Head)—stretched across decades, culminating in 1994, three years after Jean Tinguely’s death, though it remained under the vigilant supervision of Niki de Saint Phalle, who was entrusted with safeguarding the legacy of the Swiss artist.

Fully accessible to visitors, Le Cyclop offers an immersive experience—a sequence of surprises blending sound sculptures, kinetic mini-theatres, and an array of influences ranging from art brut and Dada to kinetic art and nouveau réalisme.

After spending several years at Impasse Ronsin in Paris’s 14th arrondissement—the legendary site where they met, once home to Constantin Brancusi’s studio—Tinguely and Saint Phalle relocated to Milly during the winter of 1963–64. That same year, they purchased an old inn Au Cheval Blanc. So enamoured were they with the region that in 1970 they acquired La Louvetière, a splendid former commandery in the nearby village of Dannemois, built by the Knights Templar in the 12th century. The area is perhaps best known as the home of singer Claude François’s famous watermill. But at Niki and Jean’s, who married in 1971, the atmosphere was altogether different: their home became headquarters for a vibrant community of artists working on Tinguely’s grand project.

Among them were Tinguely’s longtime collaborator Bernhard Luginbühl, his former wife, Eva Aeppli, Arman—introduced to the couple by Yves Klein—childhood friend Daniel Spoerri, and devoted assistant Josef ‘Seppi’ Imhof.

Over the years, notable guests also made their way to the couple’s home, like Formula 1 drivers Jacky Ickx and Niki Lauda, and even, in July 1987, a certain Keith Haring. In his journal, the New York artist recalled being led through the fantastical machine-sculpture by Niki de Saint Phalle herself. “Niki takes us to the forest near her house to see the ‘head’ Jean and the others have been working on for 15 years. It’s really incredible – huge and actually has movable parts. It’s better than Disneyland. You can walk inside of it and climb stairs all through it…” wrote a clearly dazzled Haring.

Winters in Milly are damp, and such a colossal construction site was frequently brought to a halt. It would take the artists more than a decade to raise Le Cyclop, all without a detailed architectural blueprint, and another fifteen years before the contributions of each participant could finally be installed. In the book Niki de Saint Phalle: Aventure Suisse (quoted in the exhibition catalogue), Niki de Saint Phalle writes:

“La Tête was one of the great adventures in Jean’s life, in mine, and in the lives of all those who took part in the work. […] It was an extraordinary sight to see all those Swiss men carrying steel beams twenty metres above the ground without flinching. It was the Swiss mountains that gave them such sure footing. […] The effort was enormous; they often burned and injured themselves. The discipline was ironclad. […] Jean financed Le Cyclop himself.”

La Tête was one of the great adventures in Jean’s life, in mine, and in the lives of all those who took part in the work. […] It was an extraordinary sight to see all those Swiss men carrying steel beams twenty metres above the ground without flinching.

Niki de Saint Phalle

Like Le Crocrodrome de Zig & Puce, La Fontaine Stravinsky, or, later, Il Giardino dei Tarocchi, Le Cyclop belongs to that remarkable family of monumental works born from the creative synergy of this unique artistic duo. Complementary in temperament as in talent, Niki and Jean continually inspired one another. Saint Phalle recalls:

“We didn’t have the same masters. Mine were Gaudí, the Postman Cheval, Matisse, Miró, Le Douanier Rousseau, Picasso, Paul Klee, Léger. Jean’s were Malevich, Calder, Duchamp, Tatlin, the Futurists. […] I believe it was my passion for Gaudí and the Postman Cheval that inspired Jean to build La Tête. […] Ping pong! Like the game, each of us pushed the other to go further, to go wilder.”

In 1987, at Tinguely’s request, Saint Phalle began work on La Face aux miroirs, the mirrored mosaic face that would become Le Cyclop’s iconic visage. Spanning more than 350 square metres, she meticulously arranged thousands of mirrored tesserae—an approach she had developed through her work on Il Giardino dei Tarocchi in Tuscany, her own magnum opus begun in the late 1970s. The undertaking was Herculean, and she would not complete it until 1991.

During the 1980s, the open-air construction site fell victim to repeated acts of vandalism. As Bernhard Luginbühl recalled, “anything that wasn’t welded down would disappear”. Jean Tinguely devised traps and decoy entrances to “wear out intruders”. Ingeniously, they installed a fake door with a false padlock, concealing a steel plate and a block of concrete.

During the 1980s, the open-air construction site fell victim to repeated acts of vandalism. As Bernhard Luginbühl recalled, “anything that wasn’t welded down would disappear”.

In 1987, the artists formally donated Le Cyclop to the French state (its conservation now overseen by the Centre National des Arts Plastiques), and in May 1994, the work was finally inaugurated by President François Mitterrand and Minister of Culture Jacques Toubon. A true emblem of utopian, collective art, the giant soon became a regional landmark.

By 2021, however, the structure had suffered significant deterioration. A year-long restoration campaign was launched: the steel framework was reinforced, and all 62,000 mirrored tesserae of La Face aux miroirs were meticulously replaced. In May 2022, Le Cyclop regained its dazzling, reflective face, roaring once again and for a long time to come, in the depths of the Milly forest. ◼

Related articles

In the calendar

Jean Tinguely,Le Cyclop, 1969–1994

FNAC 95419

Donation by Jean Tinguely and Niki de Saint Phalle to the French State in 1987

Collection of the Centre national des arts plastiques

© Adagp / Cnap – Photo © Marc Domage

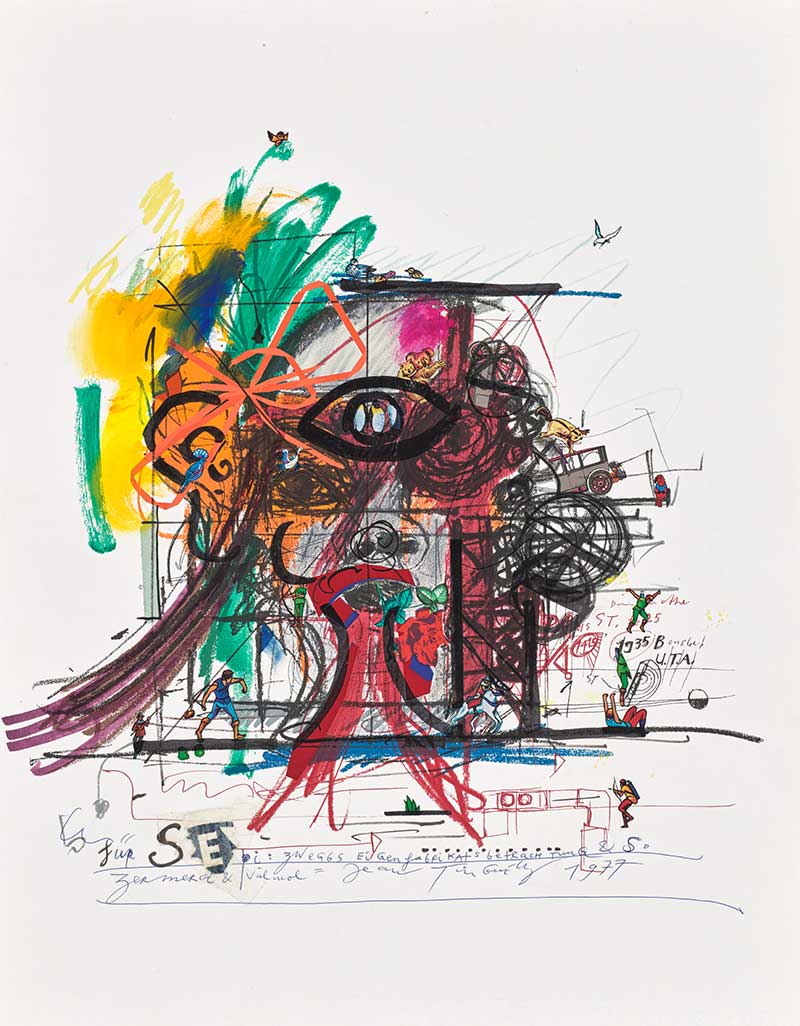

Jean Tinguely,Enhanced print of Le Cyclop, dedicated to Seppi Imhof, 1977

Felt-tip pen, ballpoint, oil pastel and collage on colour screenprint

65 × 50 cm. Museum Tinguely, Basel – a cultural commitment by Roche. Donation by Josef Imhof

© Adagp, Paris, 2025 – Photo © Museum Tinguely, Basel; photo: Fredi Zumkehr, Bildpunkt AG

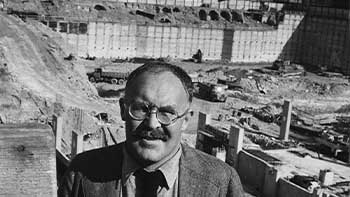

Niki de Saint Phalle, Bernhard Luginbühl and Jean Tinguely (1971)

Photo © Leonardo Bezzola, Estate Leonardo Bezzola