Pontus Hulten, an anarchist at the museum

A

rtist, anarchist … and museum director. If that combination seems unlikely, it perfectly captures the essence of Pontus Hulten (1925–2006), the very first director of the Musée National d’Art Moderne at the Centre Pompidou. Breaking away from a rather stifling museum tradition, he flung open the doors and windows—both literally and figuratively—envisioning a museum as a multifaceted space, encompassing all forms of art as imagined by Georges Pompidou: installations, performances, film, theatre, literature, dance, and more.

His boldness has left a lasting impression on the museum world, to the point of him becoming an inspirational model to other directors, eager to innovate in turn. As Sara Arrhenius, director of the Swedish Institute in Paris, explains: “There is a desire to recapture that artistic energy at a time when many museums have become institutionalised, and when experimentation is no longer possible in the way it once was.”

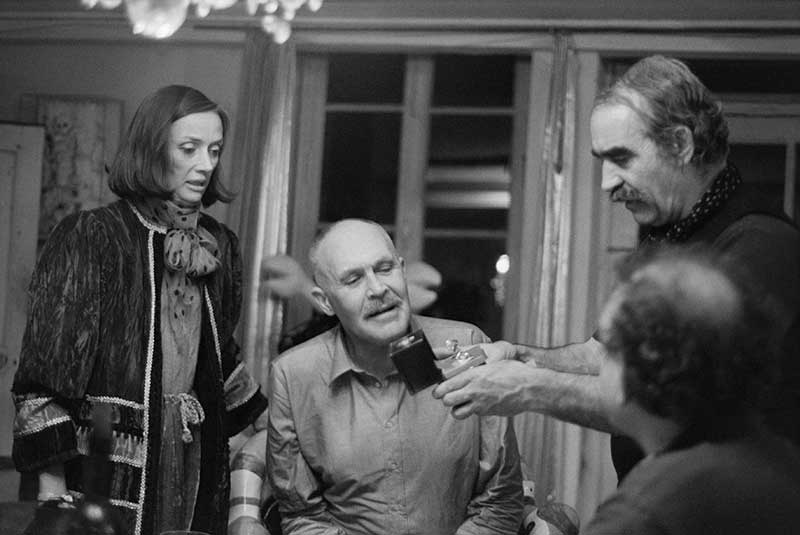

Though he maintained close ties with numerous artists, he formed a unique trio with Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely, bound by a shared intellectual and artistic kinship.

Today he is celebrated at the Grand Palais in an exhibition conceived in collaboration with the Centre Pompidou, not as an icon—which would have been a misreading of someone who always worked within a collective, surrounded by others—but through the lens of friendship, which equally defines him. Though he maintained close ties with numerous artists—Hans Nordenström, Per-Olof Ultvedt, Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage, Sam Francis, Bernhard Luginbühl, Eva Aeppli, amongst others—he formed a unique trio with Niki de Saint Phalle (1930–2002) and Jean Tinguely (1925–1991), bound by a shared intellectual and artistic kinship.

Movement as a new language

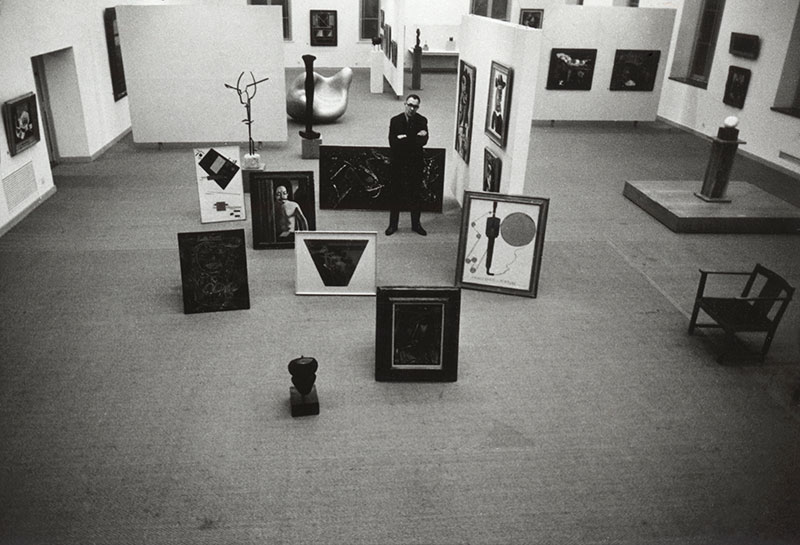

“Approaching the trajectory of two artists through their relationship with a museum man is an original proposition, but at the same time, one that felt perfectly natural,” explains Sophie Duplaix, chief curator of contemporary collections at the Musée National d’Art Moderne and curator of the exhibition. She continues: “The exhibition relies above all on the physical presence of the works by Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely, and even, by way of introduction, with those by Pontus Hulten himself, who had an art practice before giving it up, apparently after his 1954 encounter with Tinguely.”

Approaching the trajectory of two artists through their relationship with a museum man is an original proposition, but at the same time, one that felt perfectly natural.

Sophie Duplaix, curator of the exhibition

It was then that Hulten discovered Tinguely’s automates and mechanical reliefs at Galerie Arnaud in Paris, sensing in movement the promise of a new avant-garde language. “Movement in art breaks with a static conception of the world and of society […] this art illustrates pure anarchy in its most beautiful form,” he wrote in 1961 for his seminal exhibition “Rörelse i konsten” (“Movement in Art”) at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm.

A scholar of Vermeer and Spinoza, Hulten remained deeply influenced by Dada, the Bauhaus, Marcel Duchamp, and the anarchist ideas of Pierre Kropotkin (1842–1921) when he assumed leadership of the Moderna Museet in 1958. He envisioned the collection through a multidisciplinary approach, echoing Alfred Barr’s vision at MoMA in New York, and conceived the museum as a living space, inspired by Willem Sandberg at the helm of Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum.

No more the ‘museum-as-visit’ devoted to the cult of objects. I am convinced that in order to survive, [museums] must no longer be solely places of exhibition, but also spaces of creation, open to the public and attuned to life.

Pontus Hulten

“No more the ‘museum-as-visit’ devoted to the cult of objects,” he proclaimed, favouring instead a fertile ground enriched by diverse art forms, where artworks became events and visitors active participants. “I am convinced that in order to survive, [museums] must no longer be solely places of exhibition, but also spaces of creation, open to the public and attuned to life,” he declared in L’Arc magazine in 1975. That same year, he had just taken over as director of the Department of Visual Arts in the prefiguration phase of the future Centre Pompidou, which would open its doors in 1977.

Challenging the established order

The public played a central role in his vision of a “popular yet scholarly museum”, as described by Bernadette Dufrêne in the exhibition catalogue—a vision he had already implemented in Stockholm by adapting opening hours (from noon to 10pm), creating playful and cross-disciplinary exhibitions, producing truly accessible catalogues (the 1968 Andy Warhol exhibition catalogue at Moderna Museet cost just one dollar), and directly involving the public.

Sophie Duplaix emphasises: “Participation is essential in the story of this trio. Its roots lie in the anarchist spirit they shared. Tinguely had been interested in anarchist ideology since adolescence. As for Hulten, he was deeply immersed in reading on the subject. Their meeting naturally became fertile ground for countless conversations. Niki de Saint Phalle, for her part, clearly aligned with rebellion, even revolt: against her social milieu, which she saw as hypocritical and ossified; against society’s prescribed roles for women; and against cultivated, conventional art. From this came the fecundity of their exchanges, not in a strictly political stance, but in the forceful expression of their convictions through art.”

A utopia took shape: if art could not change the world, it could at least change individuals. The exuberantly colourful Nanas answered the rough, black bricolage machines in ephemeral installations, such as Tinguely’s Homage to New York, shown in 1960 in the MoMA garden, which self-destructed, or Hon – en katedral (“She – A Cathedral”), described by Duplaix.

Participation is essential in the story of this trio. Its roots lie in the anarchist spirit they shared. Tinguely had been interested in anarchist ideology since adolescence.

Sophie Duplaix, curator of the exhibition

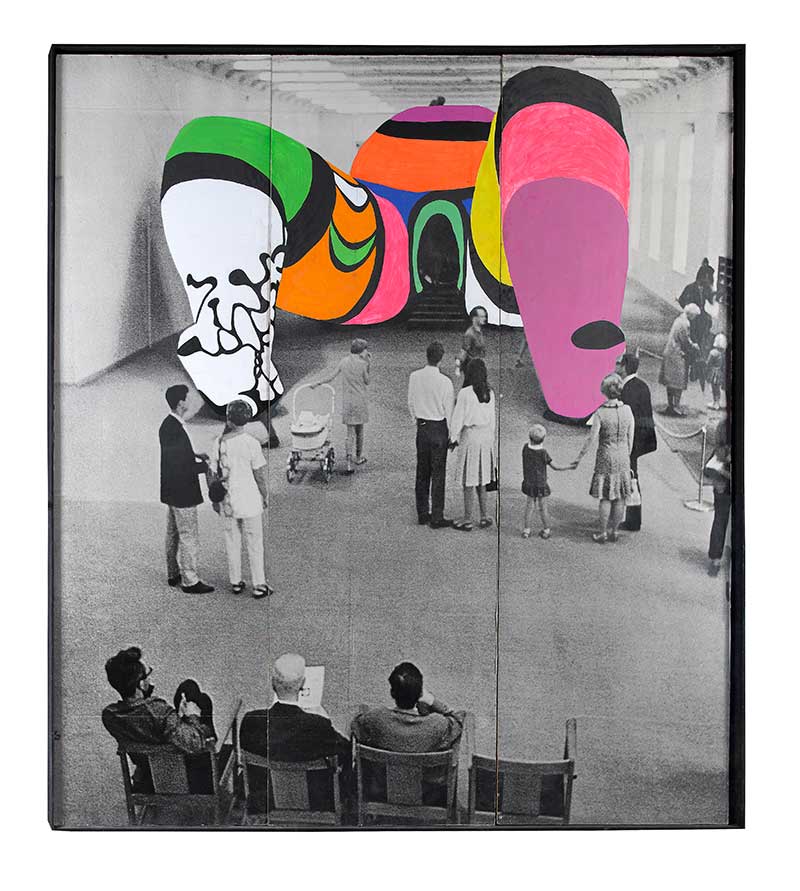

“Invited to Stockholm in 1966 by Hulten at the Moderna Museet, Saint Phalle and Tinguely, together with Swedish artist Per Olof Ultvedt, built an enormous walk-in Nana that filled an entire gallery. Inside there were all kinds of attractions: a slide, a corridor of fake paintings, a mini cinema, a ‘lovers’ bench’, a drink dispenser … The public was enthralled by the playful dimension of this work, which redefined the museum not as a site of solemn contemplation but as a space of freedom where learning could be fun.” Only the head was saved. Between acquisitions and donations, the Moderna Museet now holds 160 works by the couple.

Another exuberant moment marked the Centre Pompidou’s opening year: an installation that spilled out from the Forum onto the Piazza—Le Crocrodrome de Zig & Puce, a collaborative work led by Tinguely with Joseph ‘Seppi’ Imhof, Bernhard Luginbühl, Niki de Saint Phalle, Rudolf Tanner, Rico Weber, and Paul Wiedmer.

“Today, it would be unthinkable to offer the public a Crocrodrome at the heart of a museum institution—which was part of the proposal at the time—with artists performing acrobatics to weld the structure or spraying somewhat toxic paint! But that was also an era when artistic boundaries were shifting, when collaborative projects abounded—and it made sense in that context,” shares Sophie Duplaix. It was a joyful takeover of an institution envisioned by President Georges Pompidou, a way to challenge the status quo with an overflowing, uncontainable wave that swept across the museum’s very boundaries.

“Pontus Hulten embraced a collaborative, non-hierarchical approach, placing creativity and knowledge at the highest level,” notes Stina Gromark, graphic designer, educator, and curator of the exhibition “Keep Smiling” at the Swedish Institute, which illustrates Hulten’s significant contribution to the printed world, posters and catalogues alike.

“Pontus was a mentor to Jean”

This friendship was tinged with admiration. Pontus Hulten considered Tinguely “the most intelligent man [he had] ever met”, while Niki de Saint Phalle believed that “Pontus was a mentor to Jean. He had a profound understanding of the essential concepts of 20th-century art.”

He was a true catalyst: casting Tinguely as a police officer in his film En dag i staden (A Day in the City), co-directed in 1955 with Hans Nordenström; coining the term ‘meta-sculptures’ for Tinguely’s works; organising numerous retrospectives of both artists; and retrieving Le Paradis fantastique in Stockholm—a joint creation for the rooftop terrace of the French Pavilion at “Expo 67” in Montreal.

Pontus was a mentor to Jean. He had a profound understanding of the essential concepts of 20th-century art.

Niki de Saint Phalle

“Today, the Centre Pompidou enters its phase of metamorphosis. This is not about nostalgia, but about drawing on the early experiences of the institution, rooted in freedom and utopia. Pontus Hulten embodies this momentum, this vitality, which for years made the Centre a place like no other. We must learn to reinvent ourselves for the 2030 horizon—the date of our reopening—by embracing both the extraordinary history of the institution and the need to adapt to a new society. It is an exhilarating prospect,” concludes Sophie Duplaix. ◼

Related articles

In the calendar

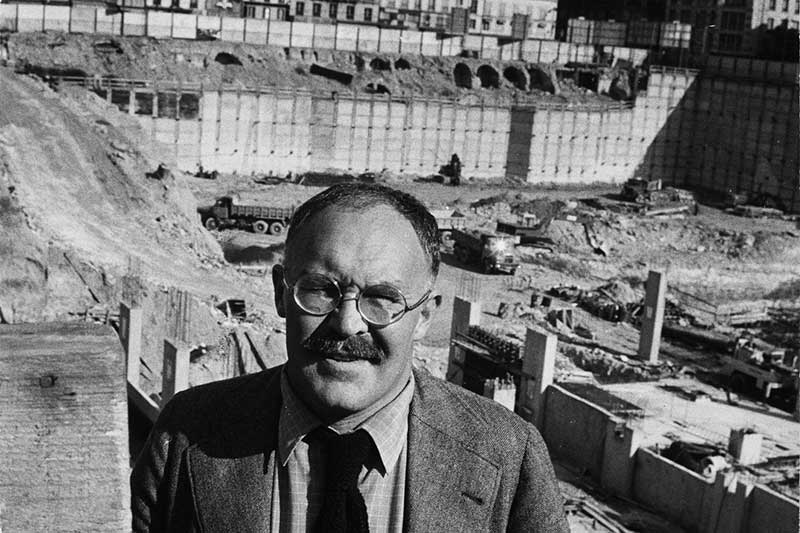

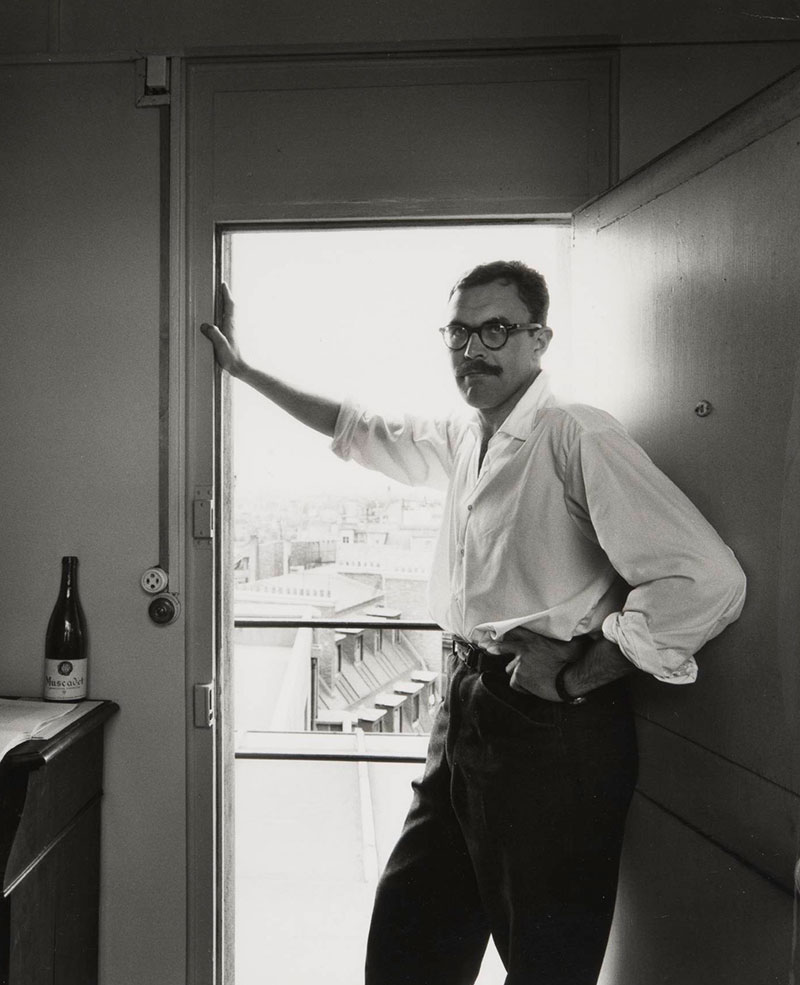

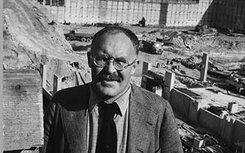

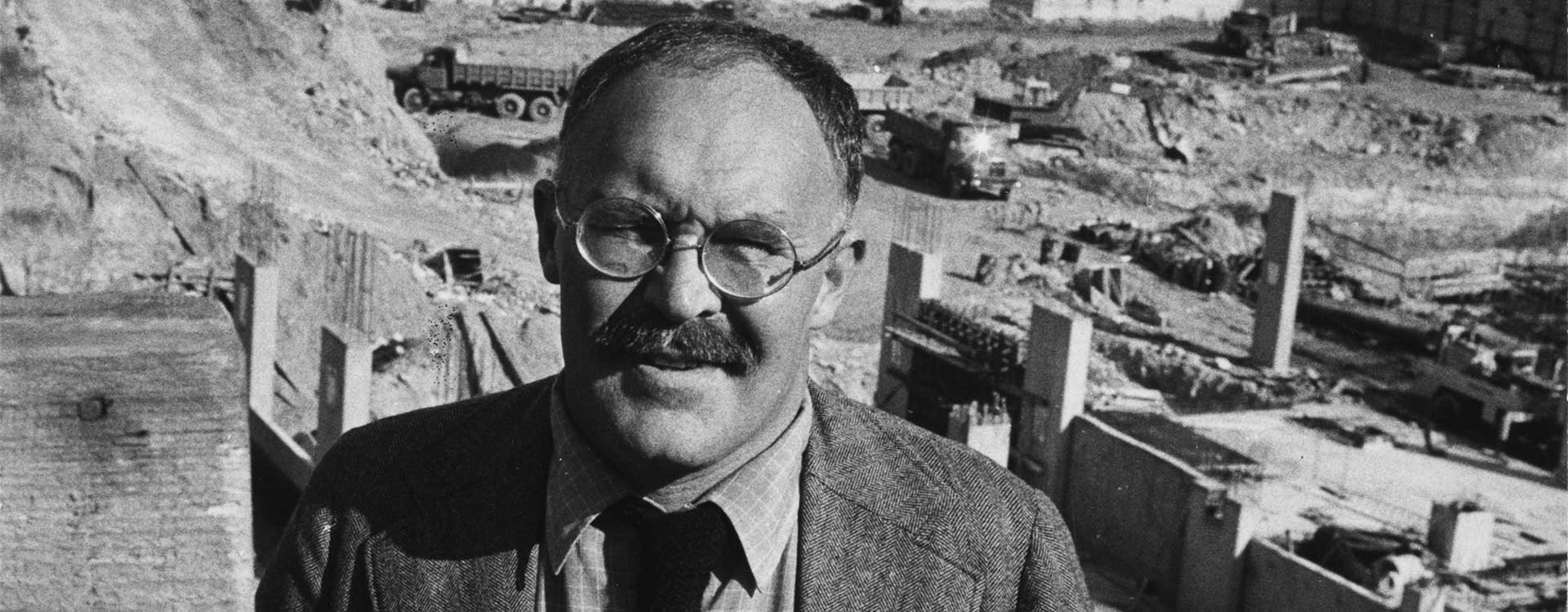

Pontus Hulten in front of the future Centre Pompidou, Paris, circa 1975.

Photo © Centre Pompidou, Mnam/Cci (André Morain)

Bibliothèque Kandinsky/Dist. GrandPalaisRmn

Photo © Estate Leonardo Bezzola

Photo © Centre Pompidou, Mnam-Cci, Bibliothèque Kandinsky/Fonds Shunk et Kender/Dist. GrandPalaisRmn, © J. Paul Getty Trust. Gift of the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation in memory of Harry Shunk and Janos Kender

© J. Paul Getty Trust

Photo © Lennart Olson/Hallands Konstmuseum

Niki Charitable Art Foundation, Santee, Californie, © 2025 Niki Charitable Art Foundation / Adagp, Photo Niki Charitable Art Foundation/Katrin Baumann © Hans Hammarskiöld/ Hans Hammarskiöld Heritage

Photo © Centre Pompidou, Mnam-Cci, Bibliothèque Kandinsky/Jacques Faujour/Dist. GrandPalaisRmn