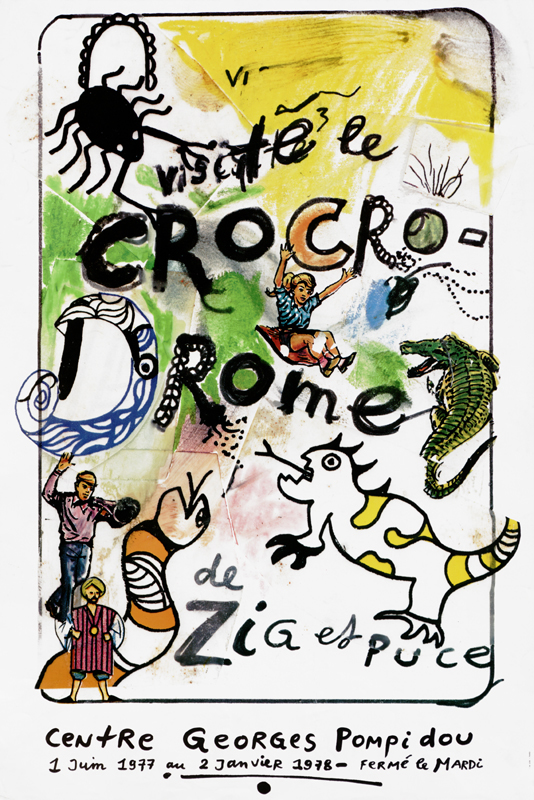

The untold story of “Le Crocrodrome de Zig & Puce” by Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely

“Le Cacadrome”. That’s the name Jean Tinguely originally wanted for the giant installation he and Niki de Saint Phalle envisioned for the Centre Pompidou—“a simple name that would work for children,” he explained mischievously in a 1977 interview on French television channel Antenne 2 (caca means pooh). Fortunately for posterity, the project’s title was vetoed by Robert Bordaz, the Centre’s president.

The collective work would ultimately be named Le Crocrodrome de Zig & Puce. “Instead of mentioning complicated names […] Niki de Saint Phalle—is it with an ‘f’ or not? Jean Tinguely—how do you spell that, with a ‘u’ or an ‘e’?” joked the Swiss artist. “Zig & Puce, that’s simple enough!”

It was early 1977, and the newly built Centre Pompidou was finally opening its doors in the Beaubourg district of Paris after years of anticipation. Welcoming visitors in the main Forum space was a strange, surreal creature made of scrap metal and plaster.

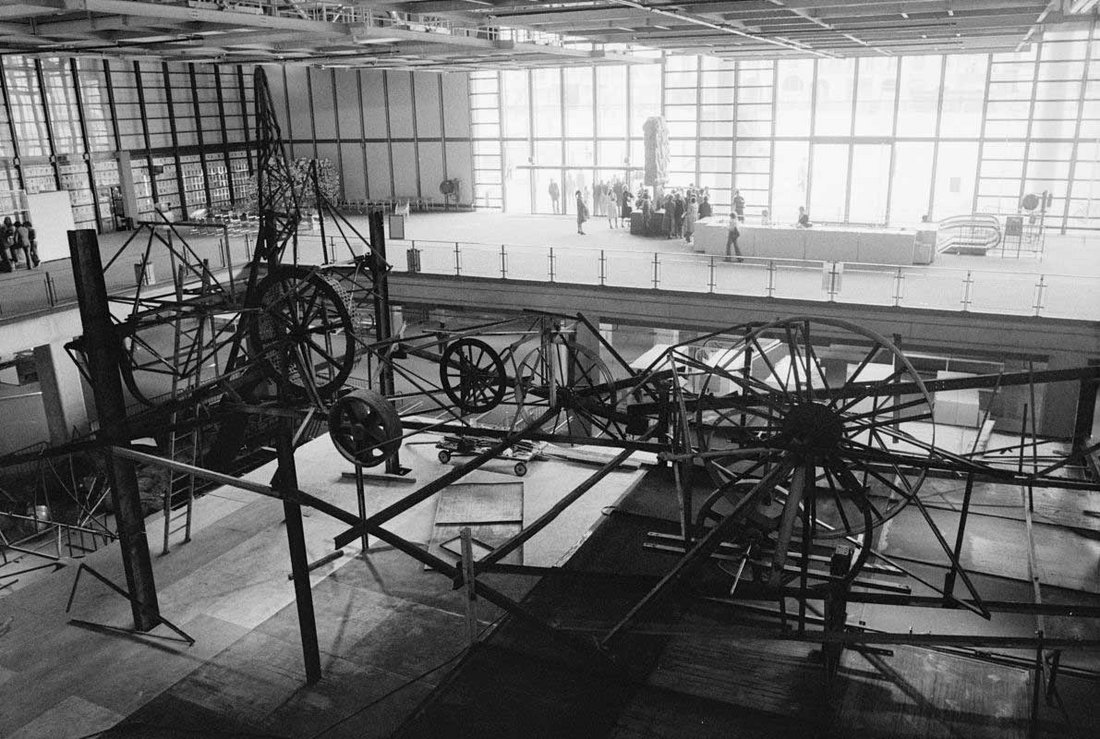

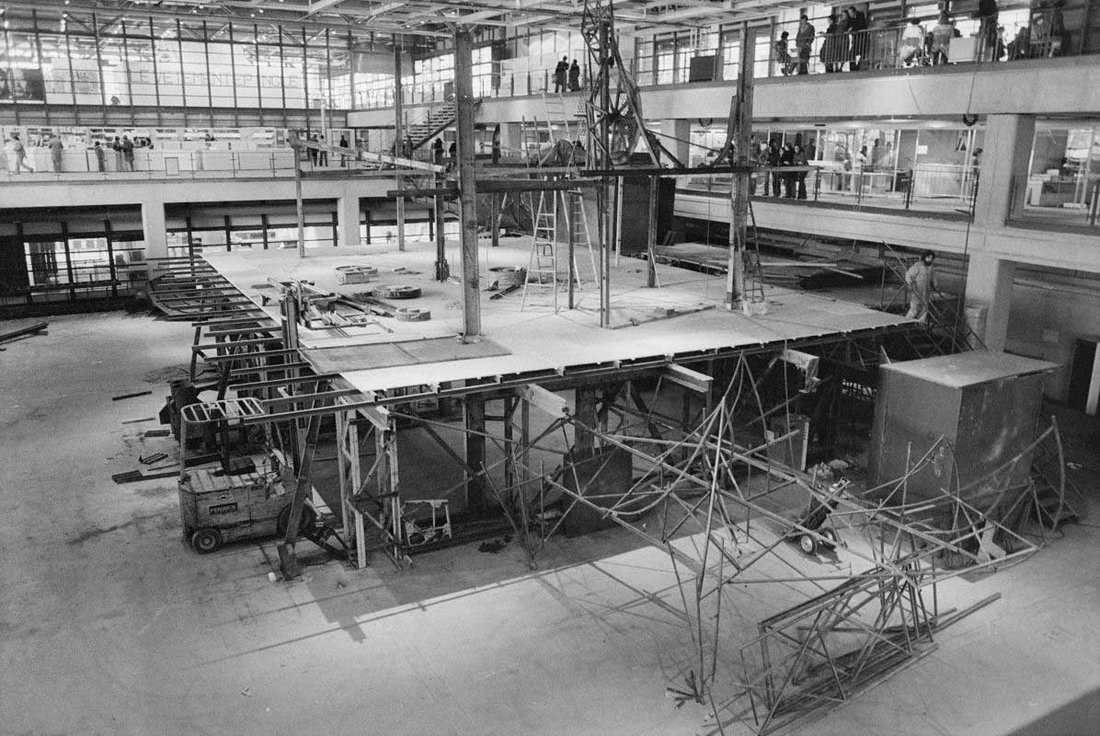

It was early 1977, and the newly built Centre Pompidou was finally opening its doors in the Beaubourg district of Paris after years of anticipation. Welcoming visitors in the main Forum space was a strange, surreal creature made of scrap metal and plaster. Thirty metres long, Le Crocrodrome de Zig & Puce was a hybrid beast sprung from the wild imaginations of the irrepressible artist duo, Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely.

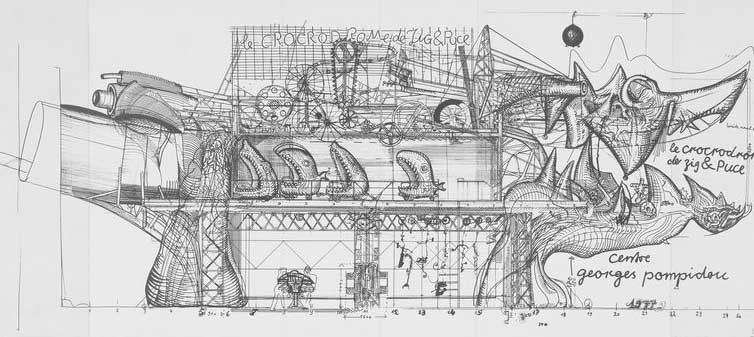

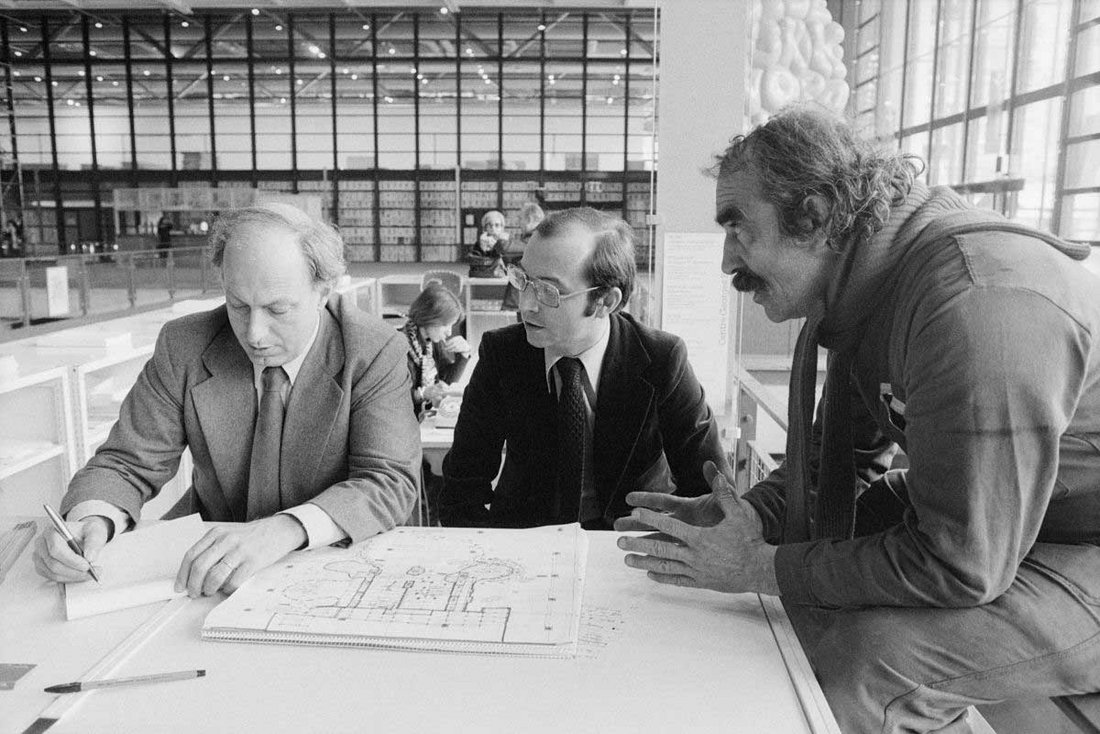

Tinguely had sketched numerous drawings for the whimsical attraction, which a project note—cited by Bernadette Dufrêne in the exhibition catalogue—described as “part dragon, part ship, part cave, part palace”. For weeks, the public looked on, fascinated, as this improbable assemblage of eclectic materials took shape.

In the spirit of Hon, the monumental walk-in sculpture created by Saint Phalle and Tinguely in 1966 for Stockholm’s Moderna Museet (then directed by Pontus Hulten), Le Crocrodrome was designed to be explored from the inside. While Saint Phalle and Tinguely acted as lead architects of the project, artists Bernhard Luginbühl and Daniel Spoerri also contributed to this exuberant collective work, which took weeks to come together.

Le Crocrodrome de Zig & Puce officially opened on 1 June 1977. For seven months, it offered young visitors a joyful, immersive playground—a kind of popular fairground blending ghost train, oversized pinball machine, free chocolate dispensers, and interactive installations.

Le Crocrodrome de Zig & Puce officially opened on 1 June 1977. For seven months, it offered young visitors a joyful, immersive playground—a kind of popular fairground blending ghost train, oversized pinball machine, free chocolate dispensers, and interactive installations, including Daniel Spoerri’s Musée sentimental. As noted in the exhibition catalogue:

“The game continued in La Boutique aberrante, where artist-made relics could be purchased. Le Musée sentimental revived the spirit of the cabinet of curiosities (the Renaissance-era precursor of the museum, with no hierarchy between artworks, either natural specimens or historical objects), offering a mix of utensils, oddities, fakes and originals—even a ‘violon d’Ingres’.”

Visitors adored this wildly imaginative space, which was a celebration of collectivity and popular entertainment. The Pompidou staff, however, was less enamoured with the cacophony of this infernal contraption, its pulleys and motors setting improbable mechanical inventions into motion with thunderous energy.

The Crocrodrome is part of a long, grand series of projects and creations. […] All these projects are monuments of another kind of art—joyful, freed from the constraints of marketability, dynamic, even active, living in symbiosis with a public that is no longer just ‘a public’, but fully part of the experience.

Pontus Hulten, first director of the Musée National d’Art Moderne

For Pontus Hulten, the visionary first director of the Musée National d’Art Moderne and the driving force behind the project: “The Crocrodrome is part of a long, grand series of projects and creations. Some came to life, others remain unrealised. In this series, ideas often blend into one another or resurface years later, more mature, more fully formed. […] All these projects are monuments of another kind of art—joyful, freed from the constraints of marketability, dynamic, even active, living in symbiosis with a public that is no longer just ‘a public’, but fully part of the experience. A new world in which the boundaries between Life and Art have completely disappeared.”

Like its older sister Hon, the Crocrodrome was meant to be ephemeral. The fantastical beast was dismantled in January 1978, but not before leaving an indelible mark on the imaginations of children and adults alike. ◼

Related articles

In the calendar

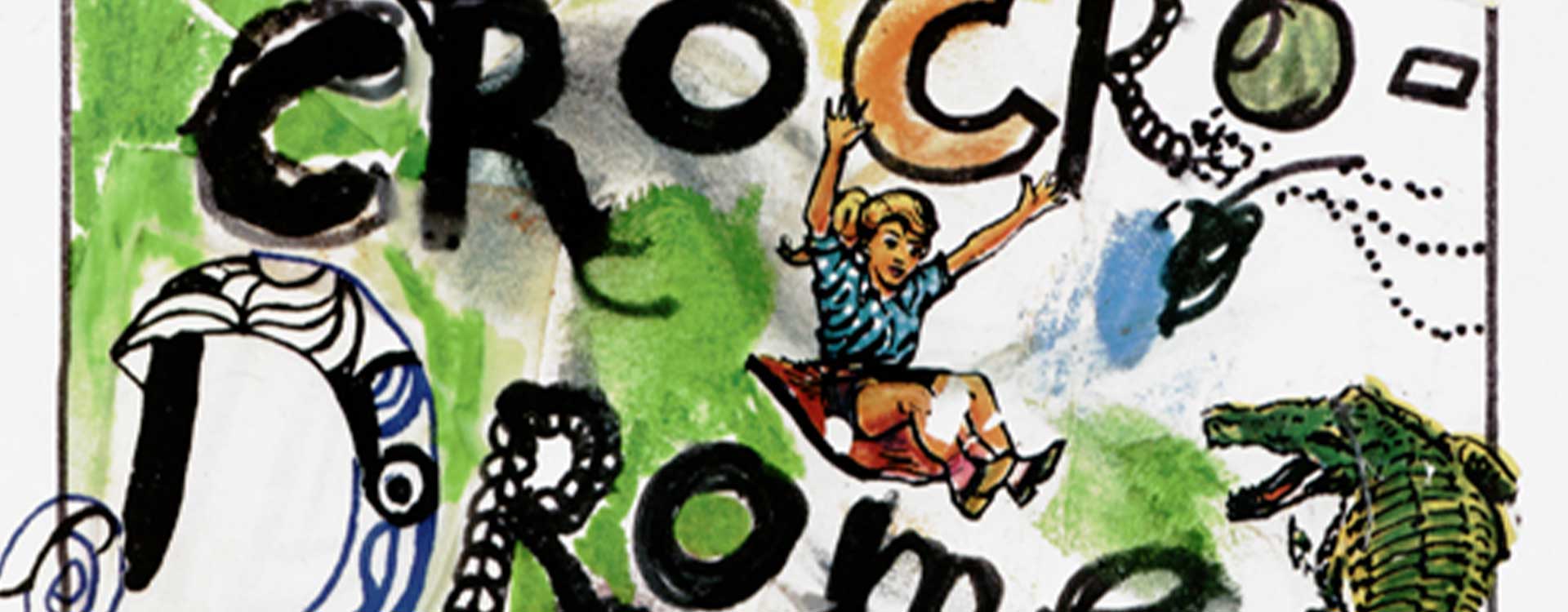

Poster for Le Crocrodrome de Zig & Puce, illustration by Jean Tinguely

© Centre Pompidou, 1977

© Adagp, Paris, 1977 and Niki de Saint Phalle

© Niki Charitable Art Foundation / Adagp, Paris

Photo © Centre Pompidou / Bibliothèque Kandinsky

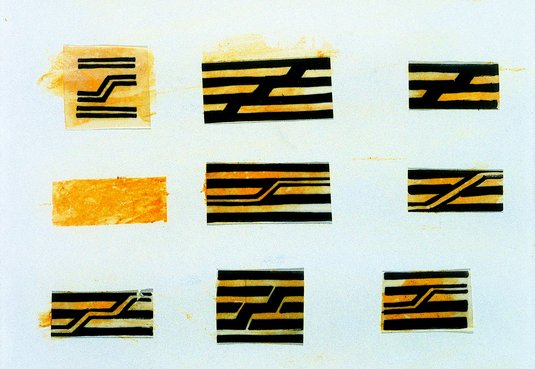

Illustration by Jean Tinguely

© Adagp, Paris, 1977 and Niki de Saint Phalle

© Niki Charitable Art Foundation / Adagp, Paris