Right bank, Left bank: A walk through the sites of “Black Paris”

Paris, a cosmopolitan stage of modernity, has taken shape through the journeys of Black artists since the 1950s. Over the decades, galleries, museums, jazz clubs, bookshops, and newspapers have formed a rich network of creative spaces. Artists from the United States, the Caribbean, South America, and Africa have been drawn to the capital for a variety of reasons: to escape racism or political turmoil in their home countries, to study in ateliers and art schools, or to seek international visibility. The history of these places reflects their commitments—to Afro-Atlantic Surrealism, debates surrounding decolonisation, independence movements, and the fight for civil rights.

In the aftermath of the war, bohemian Paris welcomed a population that valued the city’s openness and social accessibility. Several artists, including Richard Wright, were struck by the city’s topography. “Many emphasise that Paris, even in its urban layout, is not linear like American cities,” notes Éva Barois De Caevel, co-curator with Alicia Knock of the exhibition “Paris Noir”. “Paris offers winding paths where one can get lost, make unexpected encounters, wander freely.”

Paris also offers a creative plasticity across all art forms—painting, photography, sculpture, music, and literature. The city pulses with a profusion of movements: Surrealism, Existentialism, Situationism.

Paris also offers a creative plasticity across all art forms—painting, photography, sculpture, music, and literature. The city pulses with a profusion of movements: Surrealism, Existentialism, Situationism. The Martinican writer and thinker Édouard Glissant (who died in 2011) gave form to the idea of a Tout-Monde community in Paris, one that engages with the memory of multiple continents and intertwined histories.

The streets and public spaces hold a central role here, becoming political and communal arenas. The Piazza of the Centre Pompidou is part of this shared civic space, a site of encounter and mobilisation. In December 1983, it was even the culminating point of the great March for Equality and Against Racism—a potent symbol. A guided walk through the sites that, over time, recount the story of Paris Noir.

The Latin Quarter

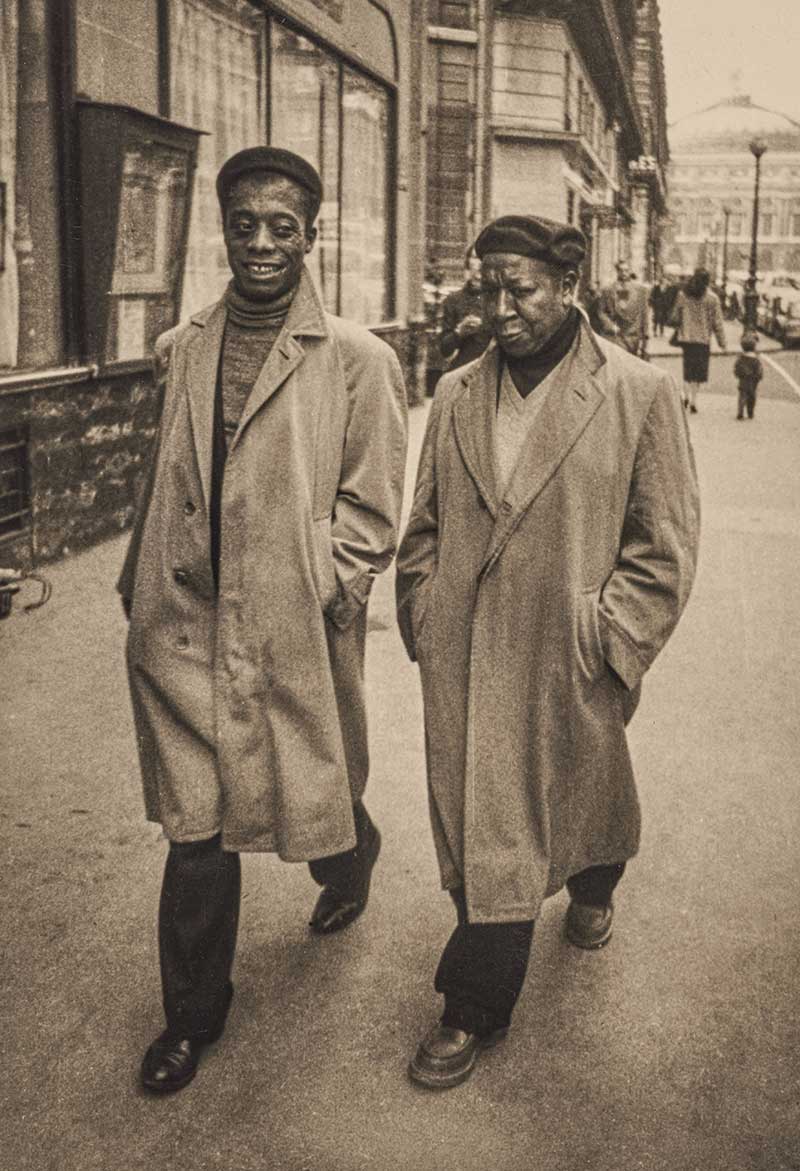

Having fled the United States, American writers William Gardner Smith (born in Philadelphia in 1927) and James Baldwin (1924–1987) emerged as key figures of the postwar Latin Quarter. A journalist for the Pittsburgh Courier following a brilliant time at university, William Gardner Smith settled in France with his wife after being discharged from the army. In Paris, he wrote several works denouncing the everyday racism of the United States.

He joined fellow American writer James Baldwin. A survivor of rape at the age of ten—committed by two New York City police officers—Baldwin, a homosexual man, left the United States for Paris’s Left Bank at the age of twenty-four. There, he embraced a form of cultural radicalism.

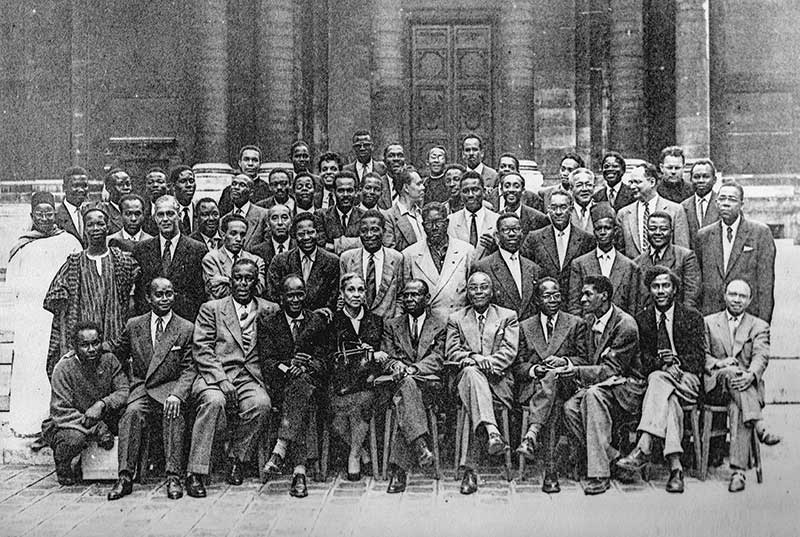

Since 2011, Parisian guide Kévi Donat has brought the Paris Noir of the Left Bank back to life through his walking tours of the capital. Along the way, he sheds light on a historical and political dimension that remains largely unknown. His itineraries retrace the paths of writer Richard Wright, playwright and journalist Maryse Condé (who passed away in 2024), Black feminist activists of the 1930s Jeanne and Paulette Nardal (pioneers of the Négritude movement), as well as Suzanne Lacascade, an Antillean writer (1884–1966). All of these women studied at the Sorbonne, “the site of the 1956 Congress, where Césaire’s speech helped shape a Pan-African and anti-colonial vision,” says Kévi Donat. And yet, not a trace of them appears in the iconic 1956 photograph.

In the same neighbourhood, the bookshop Présence Africaine remains a vital meeting place for African diasporas. Founded in 1947 […] it was there that poets such as Léopold Sédar Senghor and Léon-Gontran Damas would gather.

In the same neighbourhood, the bookshop Présence Africaine remains a vital meeting place for African diasporas. Founded in 1947 by Senegalese intellectual Alioune Diop (1910–1980), it is located on Rue des Écoles and continues to operate to this day. It was there that poets such as Léopold Sédar Senghor and Léon-Gontran Damas would gather.

Artists’ studios

Paris has also long functioned as a school. The desire to study and practise their art drew many artists to the capital. Some benefitted from scholarship programmes and enrolled in art or architecture schools—such as the École des Beaux-Arts or the École des Arts Décoratifs. Studios held a special place in the Paris Noir of visual artists. Those of Russian sculptor Ossip Zadkine and painter Fernand Léger, both 20th-century contemporaries, served as incubators for emerging talents—places of learning, exchange, and inspiration.

Zadkine settled on Rue d’Assas as early as 1910 and welcomed many young Black artists into his studio. In the 1950s, painter John Wilson—whose Mode of Production (1949) is featured in the exhibition—studied in Fernand Léger’s Montmartre atelier. So did painter Kelly Williams, who developed luminous works visible under ultraviolet light—a technique that served to reveal racial invisibility.

Many artists had studios of their own: American sculptor Harold B. Cousins (1916–1992) was photographed in his workspace in 1955; Cuban painter and sculptor Agustín Cárdenas in his studio in 1965; American abstract artist Bill Hutson (1936–2022) in 1963; and Cuban painter Guido Llinás (1923–2005) in his Vincennes atelier in 1971. American painter Herbert Gentry, born in Pittsburgh in 1919 and who passed away in Stockholm in 2003, also rented a studio in Paris.

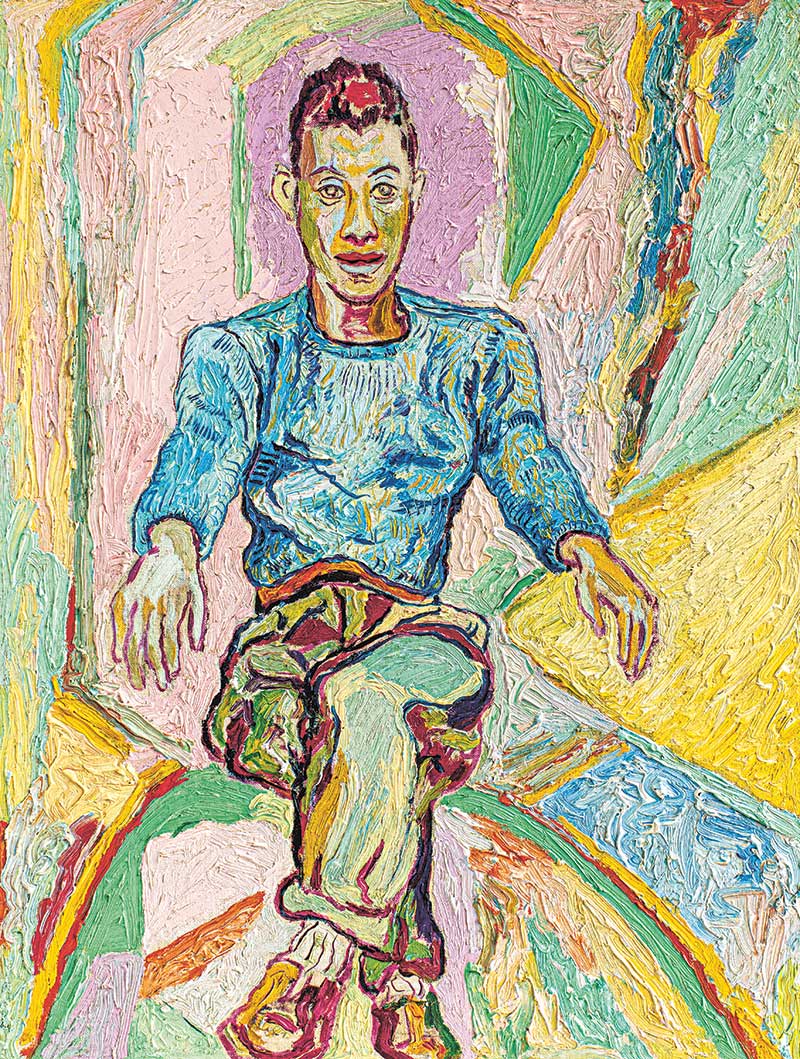

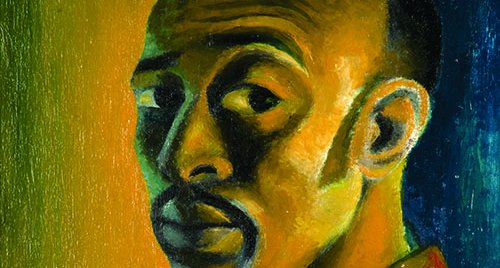

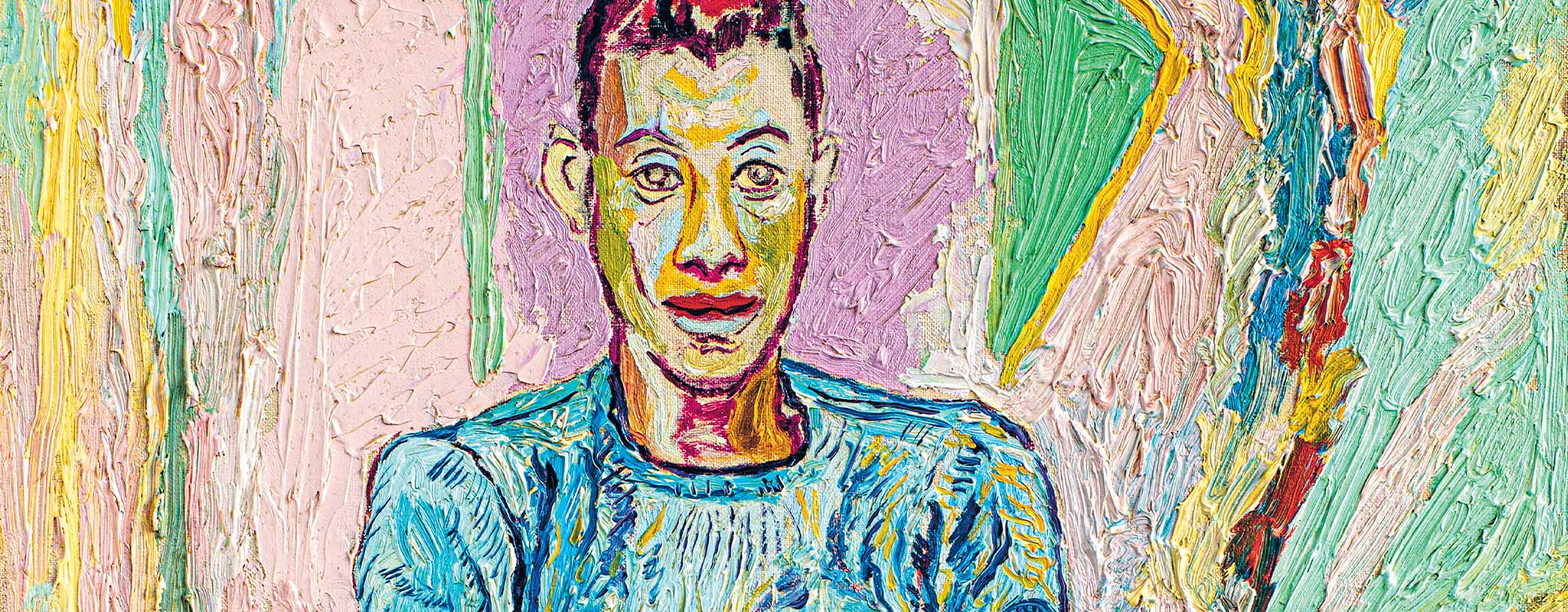

Several paintings by Beauford Delaney, on view in the exhibition, are instantly recognisable by their striking use of yellow. In the 1950s, the painter’s studio was located on Rue Vercingétorix in the 14th arrondissement.

Several paintings by Beauford Delaney, on view in the exhibition, are instantly recognisable by their striking use of yellow. In the 1950s, the painter’s studio was located on Rue Vercingétorix in the 14th arrondissement. Writer Henry Miller referred to Delaney’s Paris address as a “place of pilgrimage”. In a 1973 text featured in the exhibition, he describes it as “a tiny apartment bathed in light” where “his canvases shine with bright, vivid colours, with rainbow hues”.

Parisian jazz clubs

Naturally, music has its own strongholds in the city’s jazz clubs, where Black artists were frequently photographed by their contemporaries in postwar Paris. American photographer and filmmaker Gordon Parks (1912–2006)—whose image of a jam session on Rue du Vieux-Colombier is featured in the exhibition—captured the lively atmosphere of these Left Bank clubs. Jazz and free jazz also influenced visual artists, who channelled through their work the political force of the struggle for emancipation.

The film Harlem-sur-Seine, shown in the exhibition, pays tribute to one such musical venue where African American singer John Littleton performed. The film also mentions other meeting places: the Blue Note, La Cigale, Harry’s Bar, and Chez Haynes—venues scattered throughout various Parisian districts. Some painters depicted these iconic spaces in their work, such as Herbert Gentry (1919–2003) with his painting Chez Honey, named after a cellar club opened in 1948 that became a hub for revellers.

Galleries and museums (the Louvre and the Musée de l’Homme)

Founded by painter Haywood Bill Rivers (1922–2002), Galerie Huit—located at 8 rue Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre in the 5th arrondissement—became a gathering place for expatriate American artists who immersed themselves in the language of French informal art. Rivers’s paintings, one of which appears in Paris Noir, were inspired by the quilts he made as a child in North Carolina.

By the 1980s, a network of galleries open to artists from all continents emerged across Paris. In the 4th arrondissement, Laurence Choko opened Galerie Intemporel, where she showcased Haitian artists. In 1988, Frédéric Roulette opened Galerie Horloge in the Beaubourg district, breaking down disciplinary boundaries. Echoing the universal spirit of artistic creation, Raphaël Doueb launched Galerie Le Monde de l’Art in the 10th arrondissement in 1992, organising a prolific series of exhibitions in the early 1990s.

Beyond galleries: Museums as sites of inspiration

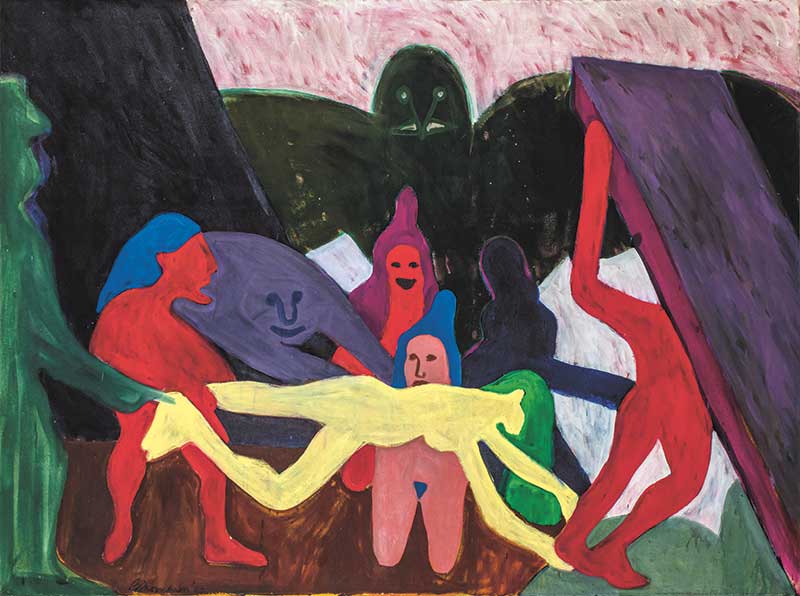

Museums, alongside galleries, are privileged spaces where young artists come to nourish their practice. American figurative painter Bob Thompson, one of whose works is featured in the exhibition, recounted that it was upon seeing The Pastorals by Poussin that he was inspired to create The Triumph of Bacchus in 1964. As they discovered classical painting and Fauvism, African artists developed subjective and critical perspectives that deeply informed their creative expression.

South African artist Ernest Mancoba was a regular visitor to the Louvre. Having arrived in Paris in 1938, he studied African objects and drew inspiration from them to create works that reinterpreted the motif of the mask.

South African artist Ernest Mancoba was a regular visitor to the Louvre. Having arrived in Paris in 1938, he studied African objects and drew inspiration from them to create works that reinterpreted the motif of the mask. On view in the exhibition is his painting Peinture 1965, inspired by a Kota mask from Gabon, which he deconstructs into vibrant chromatic variations.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the Musée de l’Homme also became a significant destination for many Afro-modernists, including Ethiopian-born painter Skunder Boghossian, who lived in Paris during that period, as well as Beauford Delaney. However, as guide Kévi Donat points out, one must avoid an overly simplistic view of the role such institutions played at the time. “After the war, theMusée de l’Homme opened its doors to Black artists, just as it had welcomed members of the Resistance during the war,” he confirms. “But at the same time, it displayed the cast and taxidermied body of Sarah Baartman, known as the ‘Hottentot Venus’, as an attraction until 1974, before her remains were returned to South Africa in 2002.” While institutions can serve as gateways to diverse forms of art, they also carry the biases and clichés of their era.

The streets

By the late 1960s, the street had become a space for mobilisation and solidarity: the 1967 protests in Guadeloupe, the movements of 1968, demonstrations in support of the Civil Rights Movement … In the 1970s, the image of Paris as a welcoming haven began to crack, as attention turned to the harsh living conditions in migrant worker hostels—conditions that photographers increasingly sought to document.

In 1980s Paris, the street—like in New York—became an open-air exhibition space. Artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–1988) embodied this underground current. Throughout the exhibition, the street is highlighted within the artworks themselves, from posters plastered on walls to depictions of protests. Urban scenes also emerge through video works: the artistic practice of Malik Sylla, concerts, cinemas, zouk dances, DJ sets, and hip-hop performances all evoke a dynamic and politically charged street culture.

Les Frigos and the Hôpital Éphémère: The alternative Paris of the 1980s–1990s

The self-managed studios Les Frigos (in the 13th arrondissement) and the Hôpital Éphémère (in the 18th) gave rise to a vibrant artistic scene. During this period, hip-hop culture began to be recognised by institutional circles. From 1990 to 1997, on the former site of the Bretonneau Hospital, the Hôpital Éphémère hosted residencies, music and dance rehearsals, and exhibitions. It also became a fashion hotspot, frequented by artist Lamine Badian Kouyaté, founder of the label XULY.Bët, who dressed stars such as Janet Jackson and Keziah Jones.

Squats, industrial wastelands, and new galleries

Squats and repurposed industrial spaces complemented a new network of emerging galleries, such as Intemporel and Black New Arts. The cultural dialogue between Paris and Africa was carried forward by organisations like La Revue Noire and Afrique en Créations, which offered vital platforms for artistic expression.

Public space remained a favoured arena. One unforgettable moment was the monumental 1999 exhibition by Senegalese artist Ousmane Sow, who transformed the Pont des Arts into a stage for his sculptures. Paris Noir stands as an invitation to rediscover the traces of those artists who made the French capital a crucible of cultural and creative innovation. ◼

Related articles

In the calendar

Beauford Delaney, James Baldwin, circa 1945-1950

Collection of halley k harrisburg and Michael Rosenfeld, New York

© Estate of Beauford Delaney, by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator, Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York

Photo Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York

Courtesy of the Estate of Beauford Delaney, by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator, and Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York

Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York

© Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York Photo Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York

Collection de l’artiste

© Adagp, Paris, 2025