Artist/personality

Otto Dix

Peintre, Graveur

Otto Dix

Peintre, Graveur

Nationalité allemande

Birth: 1891, Untermhaus (Allemagne)

Death: 1969, Singen (République fédérale d'Allemagne)

© Adagp, Paris

Her/his artworks

Biography

Otto Dix was a German painter who tried his hand at a great number of artistic movements, from Expressionism to New Objectivity, including a homage to Flamboyant Gothic. His marked interest in the shifts underway in German society runs through the entirety of his work. His aversion to war and criticism of bourgeois Berlin society made him the perfect witness in order to better understand the avant-garde movements of the 1920s.

Otto Dix was born into a working-class family and came to the world of art through his mother’s cousin, painter Fritz Amann. He then received training in the studio of an interior designer, before leaving for Dresden, where he completed his education at art school. Fascinated with applied arts, he combined an academic education with an interest in the society around him.

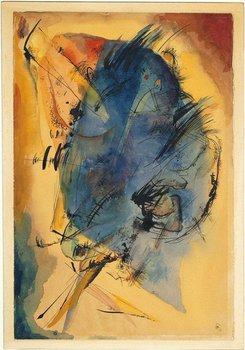

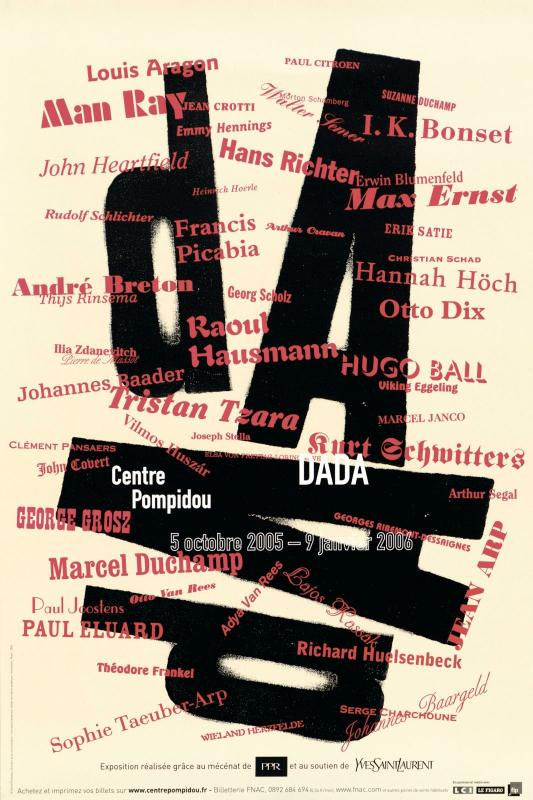

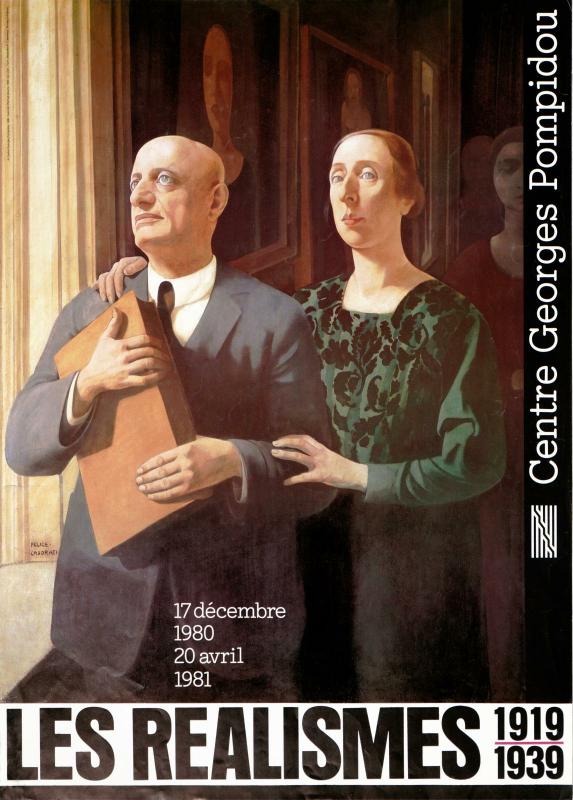

Otto Dix was starting to make art when World War I broke out. He was mobilised but, while in training, he depicted his daily life with a lively palette, bringing him close to the German Expressionist movement – which expressed existential anxiety using garish colours and stunned figures. The theme of war pursued him until the end of his life, no matter the style. In the triptych titled La Guerre (The War, 1929-1932, Galerie Neue Meister, Dresden), he returned to the German Gothic tradition and his attraction to the painting of German great masters, such as Lucas Cranach and Albrecht Dürer, presenting the most sordid aspects of war. In Erinnerungen an die Spiegelsäle von Brüssel (Memory of the Hall of Mirrors in Brussels, 1920), Dix draws on references to the Dada movement while creating interplay between textures, evoking collages. The leaders of war are represented as broken puppets, with a line that heralded that of New Objectivity.

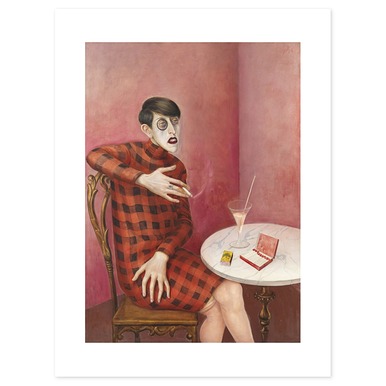

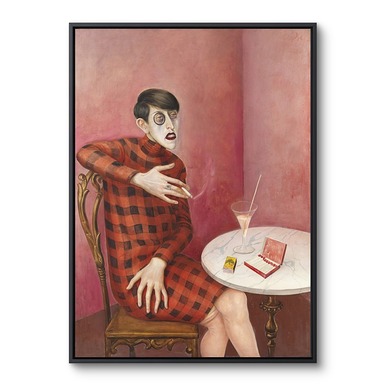

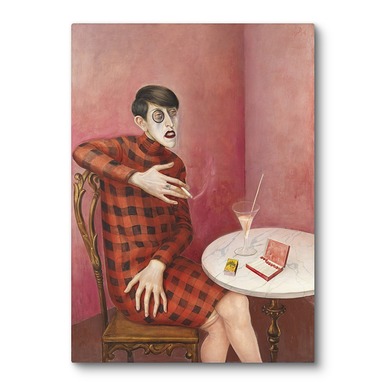

Dix would remain in this Neue Sachlichkeit movement until the end of his life. In this way, he formally opposed abstraction, which was at the heart of the works of his contemporaries at the time, and exposed the reality of society as he represented it. His enigmatic Bildnis der Journalistin Sylvia von Harden (Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden, 1926) is one of the most iconic examples of this artistic movement. In this painting, Otto Dix presents a female journalist with a cropped haircut. Sylvia von Harden is presented with an "unfeminine" attitude according to the dominant culture at the time: she works in an intellectual field and poses nonchalantly, cigarette in hand and one stocking undone, alone in a cafe. She became a symbol of emancipation, represented uncompromisingly by Dix.

Upon the Nazis’ arrival to power in 1933, Dix’s art was vilified. His works were presented in the "Degenerate Art" exhibition in Munich in 1937. He was accused of having produced avant-garde art, too far from the classical canon as promoted by the regime in force. Detained in Alsace in 1945, he continued to paint despite the conditions.

After World War II, his work gradually fell into obscurity, with German society preferring abstraction to figuration. The artist had difficulty reinventing himself, but received the Grand Merit Cross of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1959. In 1972, three years after his death, his first French retrospective opened at the Musée d’Art Moderne.

Medias

In the store