Architectural Secrets ► Architectural Secrets: The Pipes of the Centre Pompidou

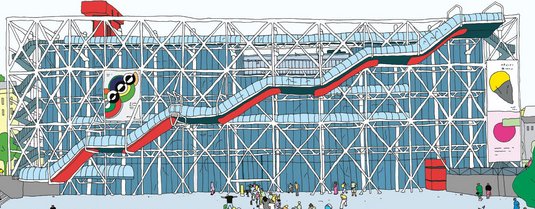

“‘Notre-Dame of the Pipes’, ‘the refinery’, ‘machine-machine’… In nearly half a century of existence, the Centre Pompidou has weathered an impressive array of nicknames—most of them aimed squarely at its exuberant network of pipes. Exposed, brightly coloured, and visible from afar, they have long been the target of exasperated detractors. When President Georges Pompidou first laid eyes on the winning design of the 1971 architectural competition, he didn’t miss a beat: ‘This is going to make people scream!’”

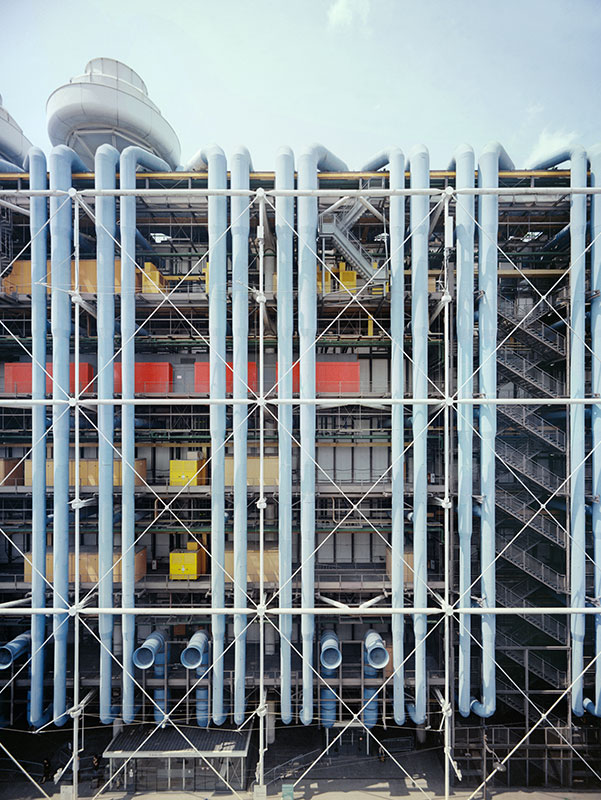

For centuries, architectural tradition strove to conceal a building’s utilities—water, electricity, gas, telecommunications. The prevailing doctrine, it seemed, was simple: “Hide that cable I cannot bear to see!” A creed rigorously applied with layers of slabs and ducts. How, then, could one not view the enormous row of brightly coloured pipes lining Rue du Renard as a provocation?

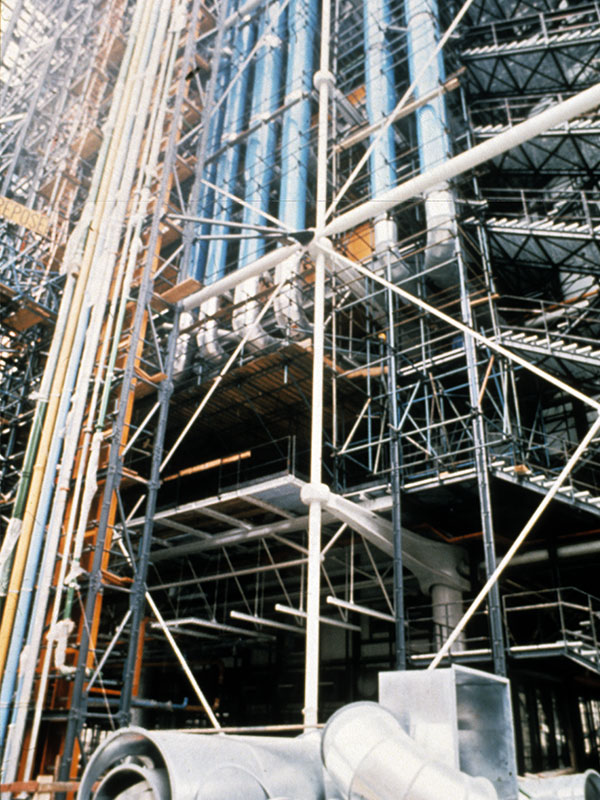

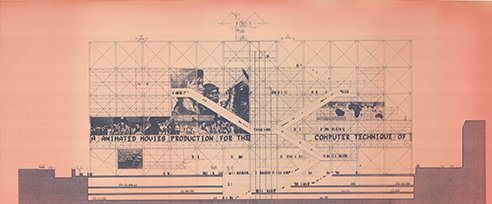

Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano, the young architects behind the Centre Pompidou, certainly knew how to stir the pot. And yet, their decision to push all the building’s infrastructure and circulation to the periphery was driven, above all, by a functional ambition: to free up as much interior space as possible. This is how Beaubourg (Centre Pompidou's nickname) came to feature six vast, open floors—each spanning 6,000 square metres—set above the public Piazza.

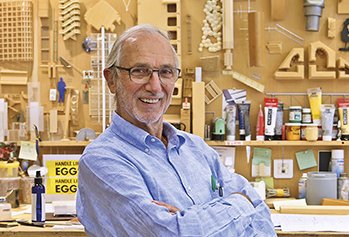

Entirely liberated from technical constraints, these flexible platforms can be reconfigured at will to accommodate changing exhibitions. This inside-out style would become Richard Rogers’s architectural hallmark—laying bare what had long been hidden. The British press famously likened his landmark Lloyd’s building in London (1978–1986) to a giant “coffee percolator.” It was a bold statement that would define the career of the architect, who received the prestigious Pritzker Prize—often dubbed the “Nobel of architecture”—in 2007.

But let us return to our Pompidou pipes. Their tangle bears no resemblance to the “cosmopompe” of The Shadoks—the cult animated television series broadcast during Georges Pompidou’s presidency (1969–1974). Quite the contrary: things are impeccably organised. Each pipe is colour-coded according to its function—blue for air conditioning, green for water, yellow for electricity, white for cooling towers, and red for the circulation of artworks, people, and fire suppression systems.

There is also a less obvious but very real virtue to exposing the Centre Pompidou’s inner workings: it greatly facilitates periodic maintenance. As Richard Rogers once put it, “A building that is easily adaptable will last longer and make more efficient use of its resources.” Since technical components are the first to deteriorate, placing them on the façade makes them easy to access and replace.

A building that is easily adaptable will last longer and make more efficient use of its resources.

Richard Rogers

This philosophy never quite caught on, and the Centre remains the world’s most emblematic example of what’s known as Bowellism (from “bowel”, meaning intestine in English). The term—coined by Michael Webb, a member of the 1960s–70s British architecture collective Archigram—might best be translated as “entrailism”. A fitting term for a building that once gave more than a few heritage advocates and artists a stomachache.

Today, however, the pipes of this so-called refinery no longer scandalise younger Parisians, who have grown up with them as part of their urban landscape. Loïc Froissart, author and illustrator of the children’s book Dans les tuyaux du Centre Pompidou (2021), has drawn them extensively. “The Centre Pompidou changes minds, sparks new ideas, and shapes ways of thinking,” he says. “That little industrial touch—that’s what I like most.”

Once dismissed as the eyesores of an architecture with nothing to hide, the pipes of the Centre Pompidou have become icons of the Parisian cityscape. One of them even served as the perch for the 1,500th work by street artist Space Invader—installed in 2024, several dozen metres above the ground. ◼

Related articles

La façade arrière du Centre Pompidou

Photo © Sergio Grazia

Toutes les autres photographies sont de Julien Lanoo, sauf mention contraire.

Retrouvez les visites d'architecture urbaine d'Hugo Trutt sur https://croquebrique.com