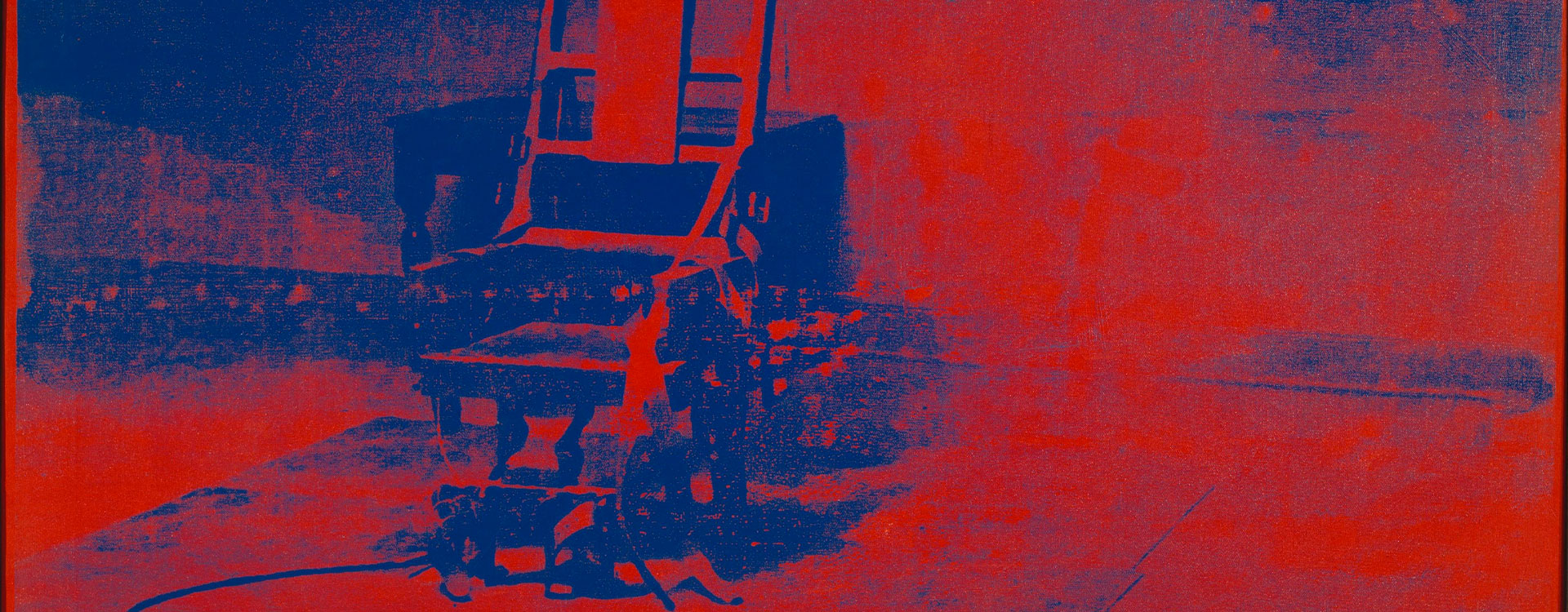

Focus on… « Big Electric Chair » by Andy Warhol

A leading figure of American Pop Art, Andy Warhol (1928–1987) became one of the most influential artists of his time in the 1960s by turning everyday products and Hollywood celebrities into modern icons. A former commercial illustrator, he mass-produced silkscreens of Campbell’s soup cans, Coca-Cola bottles, and portraits of stars like Marilyn Monroe and Liz Taylor, incisively revealing the power of images generated by consumer society and mass media.

The dark side of Pop Art

Beneath this apparent frivolity, Warhol developed early on a more sombre vein. From 1962–1963, he began drawing on press archives for photographs of tragedies—car crashes, race riots, suicides, disasters, or execution scenes—which he reworked in the Death and Disaster series. Using silkscreen printing, a mechanical process he favoured, the image is repeated until it becomes both banal and haunting, echoing the way media endlessly loops images of violence.

Using silkscreen printing, a mechanical process he favoured, the image is repeated until it becomes both banal and haunting, echoing the way media endlessly loops images of violence.

The electric chair: a political icon

It is within this context that the motif of the electric chair emerges, taken from a photograph of the empty execution chamber at Sing Sing prison on the banks of the Hudson River in New York State. In 1963, this image resonated powerfully: the use of electrocution as capital punishment was a subject of controversy in New York, while the United States was reeling from political traumas, notably the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and, shortly after, his killer Lee Harvey Oswald that same year. The growing protest movement against capital punishment—revived after the highly publicised execution of Caryl Chessman in 1960—was fuelling a national debate on institutional violence.

Big Electric Chair: a colourful spectre

With Big Electric Chair (1967), Warhol combines jarring colours, loose framing, and a degraded image to transform this instrument of power into a cold, spectral icon. The empty chair becomes an allegory of death and, at the same time, a symbol of state violence laid bare as spectacle. The occasional presence of a monochrome field beside the motif, or the serial repetition of the image, heightens this sense of detachment, as if the act of representation were fading away.

The empty chair becomes an allegory of death and, at the same time, a symbol of state violence laid bare as spectacle.

A pessimistic vision of America

Beyond its historical context, the electric chair belongs to a broader group of resolutely lethal images in Warhol’s work—accidents, police repression, the nuclear mushroom cloud. All of them express a deeply pessimistic view of 1960s America, where an obsession with fame and consumption coexists with a fascination for tragedy. According to Michel Gauthier, curator at the Musée national d’art moderne, “this depiction of an electric chair in the execution chamber, despite its colours, resembles a ‘black painting’ that conveys a fundamentally bleak vision of American society. In other words, such a painting reflects, above all, the artist’s enthralled engagement with nothingness—of which frivolity, surface, repetition, and death are merely different avatars.” ◼

The death penalty in the United States in the 1960s

In the 1960s, the death penalty was still widely practised in the United States, with electrocution being one of the most common methods. Several highly publicised cases—most notably that of Caryl Chessman, executed in 1960—fuelled a growing movement of protest: public opinion began to question both the humanity of execution methods and the risk of judicial error.

In New York, the final executions of 1963 took place against a national backdrop of political and social violence, further intensifying the controversy. This climate of tension would lead, a few years later, to the Furman v. Georgia decision (1972), which temporarily suspended the use of capital punishment in the United States.

In this context, the electric chair emerged in Warhol’s work as a potent symbol: that of state violence laid bare before the public, presented like any other image in the flow of mass media.

As of 2025, the death penalty has been abolished in twenty-three of the fifty U.S. states. Six others—Arizona, California, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee—have placed a moratorium on executions by gubernatorial decision.

Related articles

In the calendar

Andy Warhol, Big Electric Chair, décembre 1967 – janvier 1968

Encre sérigraphique et peinture acrylique sur toile, 137,2 × 185,3 cm

© droits réservés

Photo © Centre Pompidou