Focus on... “Self Portrait” by David Hockney

The question of the image, the appearance of reality, and the exploration of optical illusion—core concerns in the pictorial approach of Pop Art master David Hockney (born 1937)—naturally led him to reflect on the conditions of vision itself: the imperfect and tentative nature of seeing with the naked eye, versus the precise, even “supernatural” clarity produced by viewing through an optical device.

The “Ingres” exhibition at the National Gallery in London in January 1999 confirmed Hockney’s suspicion that the French painter (like his friend Warhol, for that matter) had made use of the camera lucida—a small, four-sided prism mounted on a rod, invented in 1806. What followed was twofold: on one hand, an extensive investigation into the optical instruments used by classical painters throughout art history (mirror, lens, telescope, camera obscura, and camera lucida), culminating in the publication of his 2001 book Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters; on the other, a prolific output of drawings—landscapes and botanical studies where close-up and distant views coexist in expanded, unstable compositions, as well as portraits of friends and self-portraits that explore the principles of optical imagery.

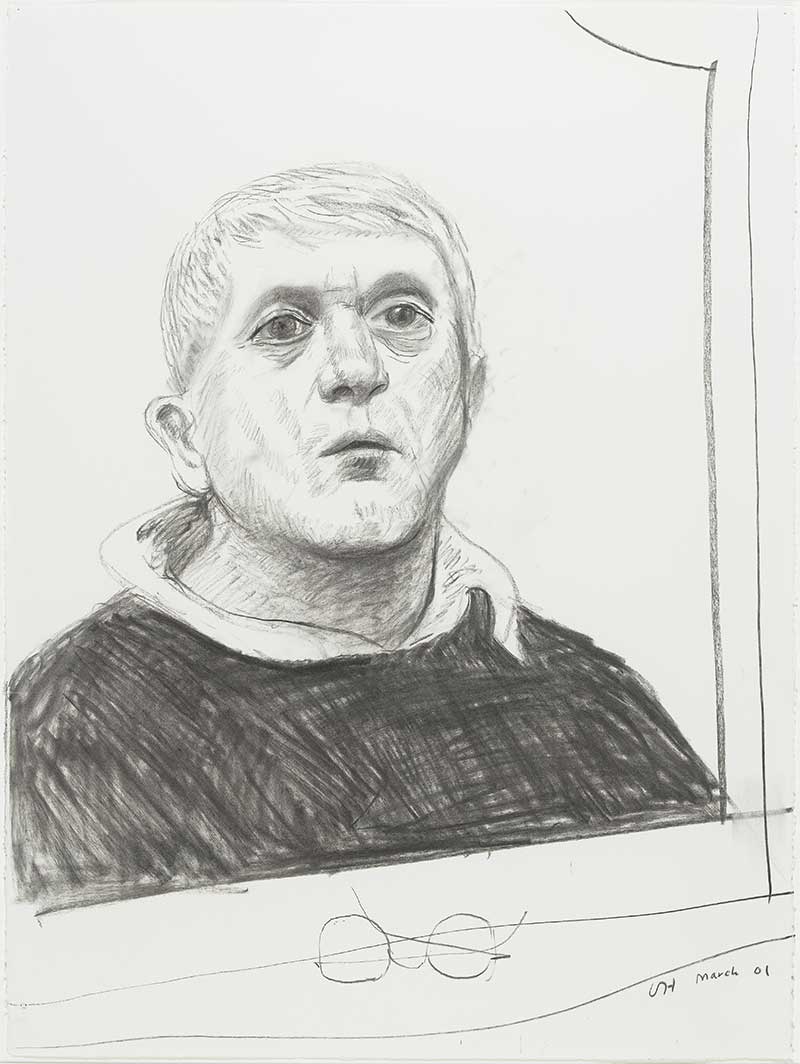

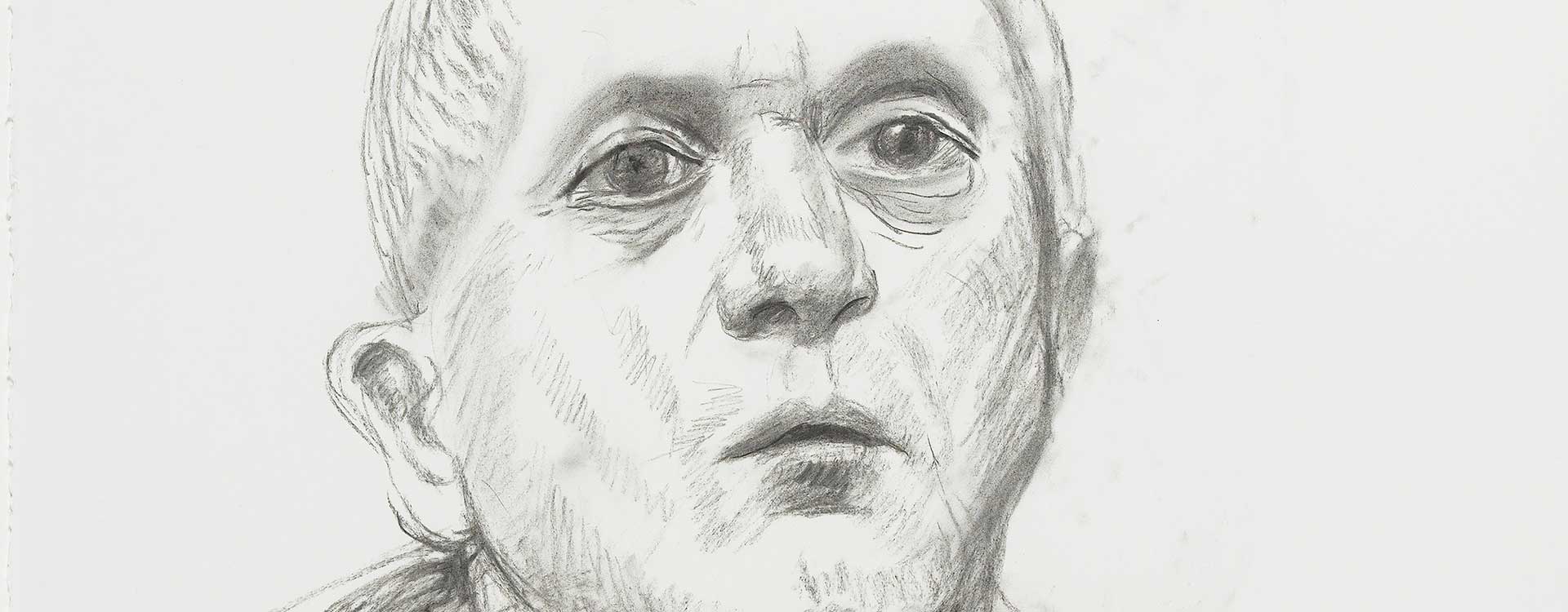

With its black bust and white collar in a style reminiscent of Ingres, this Self Portrait conveys the artist’s troubled—almost poignant—confrontation with his own reflection as rendered by a mirror, which frames his face, sets it at a distance, and shifts it into oblique view.

Hockney’s inquiry centers on what it means to capture reality, to see, and on the expressive power of the drawing hand. This body of work, unusually austere, executed solely in pencil or black charcoal, marks a moment of necessary pause in Hockney’s practice—a time of focused withdrawal that also coincides with the mourning of his mother.

With its black bust and white collar in a style strongly evocative of Ingres, this Self Portrait conveys the artist’s anxious, almost poignant questioning as he confronts the image reflected back at him in the mirror—an image that frames his face, holds it at a distance, and casts it into an oblique view: what do we see when we look—without glasses (ostentatiously placed before him)—but with the eye-as-lens wide open? The face, marked by a gravity that borders on melancholy, is entirely absorbed in the act of seeing—a fixed, almost blind gaze whose introspective depth recalls the final self-portraits of Bonnard. Combined with the drawing’s indifference to any aesthetic appeal, signalled by the hurried, unpolished line, this gives the portrait both the force of an essential presence and a sense of interiority and discipline previously unseen in Hockney’s work. ◼

Excerpt from the catalogue Collection art graphique – La collection du Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, edited by Agnès de la Beaumelle, Centre Pompidou (2008)

Related articles

In the calendar

David Hockney, Self Portrait, March 2001

Charcoal on Arches watercolour paper

© David Hockney

© Centre Pompidou, Mnam-Cci / Dist. Rmn-Gp